Stars that shone beside the slag heaps

Peter Gibbs

|

|||

|

Related Links

Teams:

England

| West Indies

|

|||

On a Friday evening in August 1959, my anticipation of the cricket match to be played the following day was more intense than usual. I had cleared a corner of the kitchen to prepare my kit. My boots and pads were barely scuffed from their previous outing, but not as pristine as they had to be for my First XI debut alongside F. M. M. Worrell. Frank Mortimer Maglinne Worrell. Sir-tobe Frank Worrell. A spotless turnout was the least he could expect for sharing a changing-room with a 15-year-old. So the match started there and then, in the kitchen, with the whitening.

Worrell had become Norton's professional three years earlier. The North Staffordshire League club had prospered through their association with the National Coal Board, owners of the ground. Like many other northern league venues, its outlook was uncompromisingly industrial. A slag heap on the scale of the Pyramids provided the backdrop, a rattling conveyor belt delivering spoil to its summit day and night.

If Worrell found his surroundings unappealing, he was too gracious to say so. The night before his first appearance, he was introduced to his team-mates at a dinner arranged by the club chairman, Tom Talbot. For a man on a personal political journey that would make him a symbol of the Caribbean drive for independence, Worrell may have been a little startled by a warm but naive Potteries welcome which included a cabaret turn by an Al Jolson impersonator singing "Mammy".

Any discomfort must have dissipated quickly, because he stayed at Norton for three record-breaking seasons, the last of which was also my first. Having performed capably in the Second XI, I had been drafted into a holiday weakened first team where, overawed and out of my depth, I found myself opening the batting. The Black Prince was at No. 3. The opposition, Burslem, had a venue in a league of its own for dank inhospitality. A sooty fug invariably clung to that corner of the region and, once a blanket of drizzle was added to the mix of particulates, visibility could be measured in feet. Burslem also had a long tradition of spectator participation.

| "Worrell, Laker and Sobers - for a cricket-mad youngster to have played alongside such all-time greats seems even now the stuff of make-believe." Peter Gibbs | |||

A concrete enclosure was home to a vociferous posse of regulars who came hotfoot from the pub to provide a scathing commentary. This was the stage on to which I and the most dazzlingly elegant member of the Three Ws stepped that day. A cutting from the late-afternoon edition of The Sentinel reveals that, after making a single, I was heading back to the pavilion. As we crossed, it is safe to assume I offered no advice to our No. 3 concerning the nature of the pitch, or how he might counter the swinging ball. The following Saturday I met much the same fate, out lbw for not very many. Unprotected by my junior-sized pads, I had been hit stingingly on the inner thigh. Worrell, this time at second wicket down, looked on impassively from the pavilion window. Though a more upholstered frame had superseded his younger profile, he was every bit the imposing figure off the field that he was on it. Sunlight through the part-netted window painted purples and blues on his polished skin, and a sharply trimmed moustache dignified his features.

His eyes, sepia-tinged around the iris, were contemplative. Embarrassingly, my own had welled up. Not only had I been dismissed cheaply, I was still feeling the radiating pain from the blow to the most tender part of my leg. I sat on the dressing-room table to watch the play, and fought back tears. Worrell saved his words of encouragement for later, but his presence alone was enough to convey the message that this was a man's game: I had better shape up. In any case his mind was probably pondering weightier matters. Four thousand miles away in the Caribbean, the campaign to make him the first full-time black captain of West Indies was intensifying under the direction of C. L. R. James.

|

|||

Worrell's own political views had remained diplomatically restrained, but his support for the People's National Movement was never in doubt. James had suggested in a front-page rant that the non-appointment of Worrell would amount to a "declaration of war". In April 1960, the board finally caved in, and so, with more important things to do, he bowed out of Norton, to be replaced as the professional by Jim Laker. One could be forgiven for thinking that the club chairman was a Potteries version of Roman Abramovich, especially when, three years later, he signed Garry Sobers. The reality was a little less munificent. Tom Talbot was in fact a local plumbing and heating contractor: no oligarch, then, but just as ambitious. At a time when a player earned perhaps £100 for a Test match, a fee of £60 plus collections for a Saturday afternoon game was no small consideration. A host of world-class cricketers were similarly lured to the northern leagues at a time when county registration rules limited their opportunities to earn a living in the first-class game.

For those who made up the numbers, it was a thrill and a privilege to be stepping on to the field with such stellar players. Before I was out of my teens I would play alongside three of the game's greatest cricketers; and, in Wes Hall and Sonny Ramadhin, bat against two of its most charismatic bowlers. Laker's written recollections of his 1960 season at Norton reveal a man reasonably satisfied with his contribution. Even so, after his distinguished career with Surrey and England, he must have thought he had fetched up on a different planet. Having arrived early for his first match, he left the dressing room to turn his arm over on the outfield. Once back in the pavilion, he found his clothes had been replaced on the peg by a policeman's uniform. The officer in question was the club's other off-spinner. "He may have taken 19 wickets in a Test match," said the PC, "but nobody nicks my changing place." It was generally agreed that Jim was bang to rights for "taking without consent".

Perhaps it was an omen: Jim never did find his place that season. The reassuring vastness of The Oval had been replaced by neighbourhood grounds with mean boundaries. Supremely subtle bowler though he was, his flight and guile were wasted on artless batsmen who would swish him unceremoniously over cow corner. Spinners were not automatically second-best to the pace bowler professionals, but to match them they had to have the bamboozle factor of Ramadhin or the Australian Cec Pepper. Jim was just too classically orthodox to run through a side match after match, and his batting was modest. For a tall, sturdy man, his studied economy of movement was striking. His short-stepping approach was almost a parody of a bowler's run-up, but the body action, when it came, produced a model of seemingly effortless propulsion. Four seasons before, I had witnessed part of his demolition of the Australian batting in Manchester. Jim smiled sceptically when I told him. "If everyone who claims to have been at the game really was there," he responded, "Old Trafford could have been filled ten times over." Taking his comment as a mild put-down, I was tempted to admit that my most vivid recollection of that game was not of him, but of Neil Harvey who, on being dismissed, sent his bat twirling high into the air like a pipe drum major. That bit of showmanship obviously appealed to my childish mind more than Jim's admirable reticence: "Just doing my job, guv," he seemed to say as he hitched up his high-waisted flannels and took his pullover from the umpire.

Perhaps if Norton had doctored the pitches as Ramadhin's club, Ashcombe Park, routinely did, Laker would have been just as lethal. But a disappointing third in the league was not what the chairman had in mind when he engaged the destroyer of the Aussies. Laker maintained he had only ever intended to play at Norton for one season; the chairman said negotiations had broken down. Whatever the truth, a new contract was not signed. However, even at 40, Jim would make another foray into first-class cricket, with Essex. By the time Sobers turned up at Norton in 1964, I was at university and acquiring my first taste of the first-class game. His arrival created a buzz, and added excitement to my vacation cricket. Like Worrell, Sobers had spent several seasons with Radcliffe in the Central Lancashire League before arriving in North Staffordshire. Whether or not Worrell had been instrumental in the transfer, he was in a good position to mark Sobers's card.

Just as Worrell had been on the verge of the West Indies captaincy in my club debut season, now Sobers stood to become his successor for the home series against Australia in 1964-65. In the previous ten years, he had performed prodigious feats, including an unbeaten 365 against Pakistan to take the Test batting record from Len Hutton at the age of 21. He had wowed the Australian public in the famous 1960-61 Test series, and returned the following year to play for South Australia and wow them again, before taking a major role in Worrell's triumphant last series, in England in 1963. Under the steadying hand of Worrell, who knew when to cut his team some slack or rein in any excess, Sobers and company were able to party with the same enthusiasm they displayed on the field. Worrell had banned card-playing among his men. If they wanted to gamble, he preferred them to lose money to bookmakers than team-mates, thereby eliminating potential friction within the dressing-room.

The offer of the captaincy, while not unexpected, threatened to bring the Sobers merry-go-round to a halt. He would not thereafter be one of the boys. Worrell had been eight years older than him when the appointment came, so Sobers's apprehension was unsurprising. With his calm authority, Worrell had become a father-of-the-nation figure, a mentor who commanded his team's unalloyed love and respect. In C. L. R. James's words, he was a "finished personality". Even though Worrell himself had anointed him as his successor, Sobers was not convinced he wanted the job of controlling a side that contained half a dozen players who considered themselves as senior as he was.

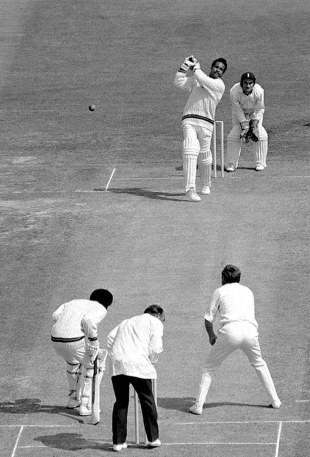

The West Indies board's letter of invitation to captain the team smouldered in Sobers's pocket for five months, his uncertainty easing only on Saturday afternoons, when he wrecked batting line-ups one after the other. In 18 matches, his 97 wickets at 8.38 secured the title for Norton - and a satisfied smile from the chairman. After dismissing the opposition for a modest total, and with the pro's collection box already doing the rounds, Garry had the disconcerting habit of putting his feet up and inviting our first three batsmen to knock off the runs.

So together we would nudge and push our way towards victory in the hope of not bothering our star attraction. The crowd, however, were less than delighted. They may have seen Sobers bowl, but they had paid to see him bat as well. In a matter of a few overs we three stooges had outstayed our welcome: being on the receiving end of impatient heckling became a character-building feature of my Saturday afternoons.

Just as Britons looked upon Nelson and Churchill as national figureheads, so first-generation West Indian immigrants took Worrell and Sobers for their heroes. During his seasons with Norton, Worrell was never short of a fan to help carry his kit from the car park, but when Sobers rolled up, a whole troupe of helpers would greet him. One would carry his bag, another his bat, another his pads - all keen to grab a piece of their idol. Thereby unencumbered, the leading man did his "Stayin' Alive" walk to the pavilion - years before Travolta sashayed along a sidewalk with a tin of paint. The lively atmosphere engendered by the West Indian professionals became even more boisterous at benefit games, when famous and not-so-famous overseas players came with family and friends. It was at a Frank Worrell benefit match in 1958 that I had first seen Sobers. The standing of the beneficiary meant he had no trouble putting together a team studded with stars.

Sobers had not yet announced himself as the pre-eminent cricketer he was to become, and I have no recall of him with bat or ball that day. What I do remember is the moment he fielded a ball in the covers. Glossy red and crisply struck, it described an arc across the turf, heading for what seemed a certain four, when Sobers pounced with such feline grace it took the breath away. The pick-up was clean and, in one silky movement, the arm looped back. With a snap of the wrist he whipped a flat throw smack into the keeper's gloves above the bails.

A more mature observer might have appreciated the liquid engineering required for such apparently fluid motion. Wiser heads could have predicted the wear and tear on muscle and cartilage. But for me, at that moment, ignorance was bliss. And even when his Travolta walk became noticeably stiffer, Sobers still seemed incapable of playing an ugly innings. As Cardus wrote, his batting was "not classical but lyrical". Inimitable as Garry was, there was no point in me, or anyone else for that matter, trying to adopt him as a role model. He was left-handed for a start, taller than me, quicker of eye and feet, and infinitely more supple. So I copied the only thing I could - I turned up my collar. Sometimes he wore his shirt unbuttoned, a` la Elvis in his Vegas days, but I lacked the nerve and the chest to risk further affectation.

Returning to Norton, I discover the pyramid of colliery slag has been levelled, environmentally cleansed, and an estate of mundane houses built in its place. I am sure local residents prefer it, but I confess to a pang of regret at the loss of a landmark. Although they no longer maintain the ground, a residuary body of the NCB remains its owner. To cover day-to-day running costs, the club rely on raffles, curry nights and small-change local sponsorship. The geometry of the ground is much the same, but the tiered seating has been ripped out for want of a crowd, and the few remaining stalwarts know to bring a folding chair. The club is no longer in the premier league, and any match-day hubbub is limited to the on-field exhortations of the players themselves.

Despite the low-octane tenor of the game in progress, the members' welcome is warm, and their joshing as dry as I remember it. "The standard's about the same as our old Second XI," says a team-mate from half a century ago. Nobody dissents. They are hopeful prospects will improve with the arrival of a new overseas professional who has been delayed in a thicket of visa regulations. "There's still value to be had on the subcontinent," one member assures me, "but it's a bind to get the paperwork through the anti-terrorist box-ticking." Something of a reassurance, then, though not especially welcome when league points are at stake.

Worrell, Laker and Sobers - for a cricket-mad youngster to have played alongside such all-time greats seems even now the stuff of make-believe. Although league clubs still enlist professionals, be they unheralded players from abroad or home-grown talent hefted to the local scene, they are unlikely to set the pulse racing like the pros of yesteryear. Today the stars are beamed to us by satellite as they follow a globetrotting schedule far removed from the colliery environs of Norton Cricket Club. And, sadly, no more is heard of the barracker who feigned objection when our star player smacked down divots in the pitch with the back of his bat. "Steady on, Sobers. There's men working under there."