A moving record

David Frith

|

|||

|

Related Links

Players/Officials:

W.G. Grace

| Wally Hammond

| Jack Hobbs

| Archie Jackson

| Bill O'Reilly

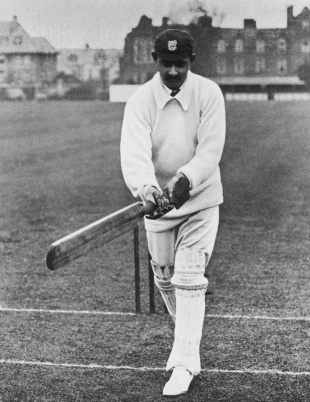

| KS Ranjitsinhji

| Victor Trumper

|

|||

Death is not absolute so long as there remain photographs or sound recordings or moving images, preferably in colour. For cricket lovers, the camera must feel like man's greatest invention: thanks to celluloid and a crank handle, W. G. Grace, Victor Trumper, Jack Hobbs, Wally Hammond and Don Bradman live on - if only in two-dimensional form and in shades of black and white, though later with audio.

It is frustrating that today's technological wizardry took so long to arrive. The earliest surviving conventional motion film is the little sequence of Ranjitsinhji wielding a wild bat in the Sydney nets late in 1897, although we have Eadweard Muybridge's multi-camera sequences from the 1880s of naked batsmen and bowlers from Pennsylvania University; the processed frames are viewable on his zoopraxiscope. A film clip of Clem Hill batting at Sheffield in 1896 was once listed, but nobody now knows where it is. Nor was proper care taken of shots of A. E. Stoddart's team and Victoria walking on to the field around the time of the Ranji mini-film.

If it's lamentable how little cricket film was taken long ago, then it's true that film was expensive and the reel-length short. Some even believed the novelty would not endure. Blessed, then, are the cameramen who filmed WG and Ranji in the nets, probably at Hastings; Joe Darling and his Australians of 1899 taking the field, probably at Cheltenham; Lord Hawke coming down the steps; and, most captivatingly of all 19th-century cricket film, the procession of the Gentlemen and the Players, taken at Lord's at a leisurely pace by Prestwich Manufacturing on July 18, 1898, to mark WG's 50th birthday. This is the only moving film of many of the great English cricketers of the era.

Elsewhere, clips of Bobby Peel, George Hirst and Bobby Abel show them motionless, either perplexed or embarrassed. So almost 40 years had passed since the first Wisden before people paid to see the cricketers magically in motion in Biograph peepshows. As newsreel companies sprang up and picture houses lured audiences, it became a way of life. Topical Budget, Pathe´ News, British Movietone, Warwick Bioscope, and Gaumont British all devised captivating stories and images, and by the 1920s there were over 20m attendances a week at UK cinemas. Gems such as the film of Gilbert Jessop, Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes in England's one-wicket victory in the 1902 Ashes Test at The Oval have been lost, but recently two barrels filled with early film shot by Mitchell & Kenyon, the Blackburn-based company, were found; further discoveries should not be impossible. The most exciting of all the M&K material was the 1901 sequence of Arthur Mold trying to demonstrate the purity of his action after being noballed for throwing. The elderly batsman in the nets is the former England captain A. N. Hornby, then president of Lancashire. A further bonus is a sweep of the players in that Lancashire v Somerset match leaving the field with the umpires, one of whom is Jim Phillips, the fearless Australian who had just terminated Mold's career.

M&K also served us well with footage of the Accrington v Church league match in 1902, even though - with the telescopic lens years away - the players are unidentifiable. In 1905, however, British Movietone created some of the best early cricket action, filming the Australians clowning around with a ball and in a chaotic team group, then skipping down the steps at Trent Bridge. Further close-up action shots at Lord's do them little justice: Clem Hill and Joe Darling look the part, but Warwick Armstrong and Monty Noble clumsily overbalance, perhaps jittery as they perform for this strange new contraption; Victor Trumper is let down by a ball tossed at his throat. The only other known clip of this deified batsman shows him falling over after being run out in a Sydney Test. Four years later his long funeral cortege was captured on celluloid. At least his spiritual successor, Archie Jackson, was beautifully filmed during a net session in 1929.

| The 1930 Ashes Tests were well covered by the newsreel companies, and some footage is now available on the internet, but the abiding mystery is that there is nothing on Bradman's greatest innings, his 254 at Lord's. | |||

Another precious pre-Great War film was shot at Horsham in 1913, when Sussex played Lancashire. The Tyldesley brothers go out to bat, and the only known footage of Albert Trott shows him shuffling out to umpire. The match action is far away, but the elegantly dressed spectators reflect the idyll of pre-war England in summertime. Topical Budget made newsreels from 1911 to 1931, and were responsible for some significant footage, notably of England's recapture of the Ashes at The Oval in 1926. Jack Gregory blazes away with bat (no gloves) and ball, Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe build towards that glorious victory, and young Harold Larwood and the elderly Rhodes prise out the Australians. This major feature set the pattern: newsreels would now give cricket's great events due attention - even if identifications were sometimes adrift. The 1930 Ashes Tests were well covered by the newsreel companies, and some footage is now available on the internet, but the abiding mystery is that there is nothing on Bradman's greatest innings, his 254 at Lord's. In 1948, his famous last-innings duck was recorded clearly enough, although the inserts of leg-spinner Eric Hollies are misleading: he was bowling over the wicket.

A substantial silent Life of Jack Hobbs is absorbing, and Australian filmmaker Ken G. Hall made an enchanting sound documentary called That's Cricket in 1931. At Trent Bridge, a Mr Stevens used his 16mm camera to film county and Test matches during the 1930s, invaluable reels now safe with the National Film Archive. From 1946, with television still in its infancy, newsreels remained major attractions. After England won the Ashes at The Oval in 1953, I spent all day in a cinema watching repeat showings, and still treasure indelible images of Len Hutton's running catch to dismiss Neil Harvey off new boy Fred Trueman, Tony Lock's spine-bending ecstasy after taking a wicket, and Denis Compton's sweep to seal the triumph. A couple of years earlier a landmark feature was Elusive Victory, produced by E. W. Swanton and filmed by 24-year-old John Woodcock. This monochrome film of the 1950-51 Ashes, with match footage, player close-ups and informal scenes, might have set a pattern while television was still emerging; but it was not to be, apart from some important tour features shot in colour by Rothmans in the 1960s. Cricket continued to be an ingredient in many a feature film, however, and The Final Test (1954, written by Terence Rattigan) centred on a game at The Oval, with current England players taking bit parts.

Elsewhere, numerous feature films have included brief cricket scenes, many staged clumsily. From India, though, Lagaan (2001) was a highly entertaining musical drama with a cricket match as the central theme. As Wisden reached its century in 1963, newsreels were in decline, and television was becoming the all-powerful medium. With the advent of video recorders, cricket lovers began creating film libraries of their own, collecting highlights, interviews and sometimes even live play. Nostalgia and plain curiosity created a renewed interest in old film. In 1981, I persuaded the British Film Institute to stage annual cricket evenings at London's NFT, showing material from 1897 onwards, fresh discoveries often garnishing the programmes. Percy Fender's 16mm footage from 1928-29 has been the latest find, containing the earliest film of Don Bradman and Archie Jackson. Jack Badcock's high-quality record of the Australians' tour of England in 1938 has also been shown for the first time in public; so too, at the NFT, Jeff Stollmeyer's film of West Indies' 1951-52 tour of Australasia. Although damaged in storage, it contains some magical sequences.

Probably overshadowed by South Africa's post-apartheid transition, an invaluable 30-part history of that country's Test history from 1888 to 1970 was overseen by Brian Bassano, and is now a video rarity. Something similar was made to mark New Zealand's cricket history, while Jack Egan - utilising Cinesound's newsreel library - produced several videotapes in Australia, including interviews with Bradman and Bill O'Reilly. In 1982, I researched and scripted Benson & Hedges Golden Greats: Batsmen, with John Arlott the key presenter (long after he had featured in the charming British Council film Cricket, which centred on the 1948 Lord's Test). A companion to that video was one on bowlers, presented by Peter West. Newsreel and privately shot film made up the historical content.

It is a good time now for vintage cricket film. Innumerable clips from the newsreel companies' archives from the past 100 years and more can be watched on the internet, with countless delights on YouTube. With cricket fans wielding mobile phones - mainly to capture grinning players signing things or with arms around fans' shoulders - the game is now awash with images, in stark contrast to those long-ago times when the early marvels of cinematography were scarcely understood by cameramen or cricketers.

Film treasures from the 1930s have been rediscovered. As 16mm cameras became available, cricketers took them on tour. The sight of an old photo of Australian batsman Bill Brown holding a movie camera prompted an enquiry as to the fate of those films: "Oh, I think I lent them some years ago but they weren't returned." Fortunately, others - such as Badcock and Clarrie Grimmett (who filmed the 1930 and 1934 Ashes tours) - were more careful. Fast bowlers H. D. "Hopper" Read and Maurice Allom recorded some fascinating 1930s action around England and on tour, and since the 1950s much important footage has been shot by the Bedser twins, Charles Palmer, Arthur Morris, Alan Oakman, Ken Barrington, Trevor Bailey, Johnny Wardle, Keith Andrew, Frank Tyson and Jack Robertson. Much of this material was shown at the London film nights, while MCC have produced several DVDs.

Oakman's colour sequence of Garry Sobers bowling fast could not be bettered, and his shots of Barrington dressed as WG are another treat. Among Bailey's high-quality films is rare footage of Australia's mystery bowler Jack Iverson, as well as Lindsay Hassett's dismissal by Doug Wright's fast legbreak, the equal of the Warne-Gatting ball of the century over 40 years later. These amateur home movies inevitably contain many scenes around swimming pools, on ships' decks, at airports, and action footage too far away, but there are also some high-quality shots from net practice. One of Wardle's films even features pin-up Sabrina on the pitch with Hutton. Sid Barnes, the rebel Australian batsman, made a film of the 1948 tour and showed it for the benefit of charity, though the cynics, knowing "Bagga's" proclivity for a few quid, felt Sid was his own all-consuming charity. When he was carried into the dressing-room in 1948 after taking a ferocious blow to the kidneys at short leg, he winked at the team-mate holding his camera and said: "Didya get that?" The whereabouts of the complete film are no longer known. Perhaps it simply wore out.

Cricket on early television was seldom recorded and retained. One blissful exception was in 1953, when England won the Ashes. The heroes were interviewed by Brian Johnston on the top deck of the Oval pavilion, with young Trueman displaying a shyness he would later overcome. DVDs have succeeded videotapes, and the Australian television mini-series on Bodyline sold well. This was regrettable in one way, since it contained many ludicrous inaccuracies; some folk, it seems, find the truth dull. The BBC and the ABC have both made admirable documentaries on that most famous of all series. With the archives bulging, future generations should be satisfied.