An all-time great, and no denying

Shehan Karunatilaka

|

|||

|

Related Links

Interviews : 'I can't please everyone'

Peter Roebuck : In a freakish league of his own Players/Officials:

Muthiah Muralidaran

|

|||

A dangerous confession: I have been a Murali-sceptic for some time. This is not something that should be admitted, in public or otherwise, if you are Sri Lankan and fear being lynched.

Make no mistake, I am no Murali-denier. Who can possibly deny the man's genius, his artistry, and his quiet dignity? But when first I saw him in 1995, bamboozling the Kiwis in Sri Lanka's first Test series win abroad, my reaction was that there was dodginess at work - dodginess concentrated around the elbow region. I wasn't the only one.

At the time I hadn't read the rules on what constituted a chuck, but it seemed to be all about elbows: whether they straightened or whether they bent. My view of chucking mirrored conventional views on pornography: hard to define, but I would know it when I saw it.

For those, however, who saw Murali, who truly saw the man's wizardry, there is far more to him than a curious elbow. The eyes that glare like an All Black mid-haka, the wrist that flaps at improbable angles and, unseen by most, the shoulder that all but dislocates at the point of delivery.

And then there was the glorious loop, the exquisite drift, the subtle drop and the not-so-subtle turn. The offbeat rhythms, the never-ending spells, the untouchable records and the parade of whispering naysayers.

It may be a statistical fact that Murali is the most prolific player to hold a cricket ball, but chat to the umpires whose reputations he tainted, the ex-players offended by his supple action, or the punters who post on the walls of Facebook pages questioning his legitimacy, and they'll describe a charlatan whose ill-gotten wickets should be expunged from the records.

But for the Sri Lankan fan - even for the sceptic - he was beyond spectacular. The first bowler from our fair isle to strike terror into the hearts of international batting line-ups; the one reliable constant in a country overrun with unreliable inconsequentials; a famous Tamil who could sidestep racial politics; a wronged man who threw no tantrums; a genius who almost literally rewrote the rules.

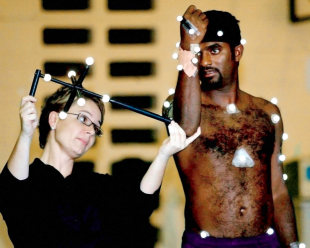

Had he played in an earlier era, the backroom sniggers would have swiftly snuffed out his career. And while his detractors may blame modern cricket's geopolitics and its misplaced political correctness for allowing his career to flourish, he was saved by something far less insidious: science.

The Murali saga unveiled a somewhat unsavoury fact, which many have been unwilling to swallow: under the biomechanical microscope, everybody chucks to some extent. The perfectly straight elbow is as much a myth as the idea that cricket is a sport played by gentlemen.

Bowlers can now flex their elbows up to 15 degrees at the point of delivery. Previously spinners were limited to five degrees of flexion, and fast bowlers to ten. The ICC argued 15 degrees was the point at which a chuck became visible to the naked eye; others pointed out that this was convenient, since Murali's doosra had been measured at 14. But over-zealous Murali defenders will tell you that supposed paragons of orthodoxy, such as Shaun Pollock and Glenn McGrath, were saved from embarrassment by the 15-degree ruling.

Over the past two decades, excitable Sri Lankans hurled these arguments across chat rooms and bar rooms at anyone who dared use the c-word to describe our Murali. But not me. Of course, I was delighted to see science and rationalism - western imperialism's hammer and sickle - being used by the East to clear a bowler's name; tickled to see those who live by the sword being put to it. And yet the sceptic lingered.

| Matches | Overs | Runs | Wickets | Best | 5w | 10w | Avg | SR | Econ |

| Tests - 133 | 7339.5 | 18180 | 800 | 9-51 | 67 | 22 | 22.72 | 55.0 | 2.47 |

| First-class - 232 | 11155.3 | 26997 | 1374 | 9-51 | 119 | 34 | 19.64 | 48.7 | 2.42 |

| Overs | Runs | Wickets | Best | 4w | 5w | Avg | SR | Econ | |

| ODIs - 350 | 3135.1 | 12326 | 534 | 7-30 | 15 | 10 | 23.08 | 35.2 | 3.93 |

| List A - 453 | 3955.4 | 15270 | 682 | 7-30 | 17 | 12 | 22.39 | 35.21 | 3.84 |

| T20I - 12 | 47 | 297 | 12 | 3-29 | 0 | 0 | 22.84 | 21.6 | 6.31 |

Could a lab experiment replicate the conditions of a live match? Could scientific tests, on which a legend's career and a nation's hopes hinged, ever be free of politics and emotion? And was the world really going to buy the optical-illusion excuse?

But here are some indisputables. Even those who bray "no-ball" from the stands of Australian cricket cannot claim Murali to be a cheat. He did not manufacture his action to gain an unfair advantage over the world. It evolved haphazardly, like many great things in Sri Lanka. We'd like to believe our tiny island nurtures innovation and unorthodoxy but, truth be told, we hardly notice when things are off-kilter, and rarely do we try to fix anything, broken or not.

Even those who dispute the legitimacy of his 1347 international wickets cannot deny his exemplary conduct in the face of provocation. A few petulant swipes at ex-cricketers late in his career aside, there have been no bitter diatribes, no drunken binges, no punch-ups in bars. Had the great Shane Warne been subjected to this much vitriol, would he have responded with a smile and a shrug?

Speaking to Murali's biographer, Charlie Austin, I catch a glimpse of an unseen Murali, of the man behind the bulging eyes and the assassin's grin. I hear about the obsessive preparation, the hours spent landing it on a spot in nets, conjuring up tricks and perfecting the unplayable; months spent poring over cricket footage, ball in hand, flexing and tweaking until the leather became part of his skin.

I also hear about the stage fright that formed a prelude to every game, even in the twilight of his career. One can only imagine the pressure of being expected to take a wicket every time the ball was tossed to him, the certainty that he would claim a five-for in each game, regardless of the opposition or surface.

Sri Lankan bowling didn't just rely on Murali: we made him carry us. In our admittedly short Test history, only four Sri Lankans had at the start of 2012 taken 100 wickets: Lasith Malinga (101), Rangana Herath (119) and Chaminda Vaas (355). Murali has 800. And that's it - not so much a gulf as an abyss.

He was never interested in being a racial icon, playing power games or claiming the captaincy. One doesn't become the greatest bowler of all time by being distracted. It was almost like race was incidental to his monumental talent. He had lived through his father's biscuit factory in Kandy being burned by bigots in the 1970s, but steered clear of pressure groups who wished he would voice their causes. His cause was making a cricket ball change direction. And in a nation filled with division, he was the one cause we could all get behind. And boy, do we miss him.

Austin tells me of Murali's influence in the dressing room, where he took younger players under his wing and kept the politicians at bay; about his unused strategy of reinventing himself as a legspinner, had science and a burly captain not rescued him from the wolves; that he has built almost as many houses for tsunami victims as he took international wickets.

But it wasn't any of these that finally swayed me. It was a cricket show presented by Mark Nicholas, a man who appeared as much of a sceptic as I, dressed up in an arm brace and presented in super-slow motion. What had first appeared dodgy now revealed itself to be miraculous.

The Laws speak of elbows, but they say nothing of wrists and shoulders, perhaps because no one has been gifted with such suppleness or been capable of such contortion. I finally got what the optical-illusion thing was all about. From certain angles, it did appear that the elbow was straightening, even when it was locked in place by steel and plaster. Murali's action was unorthodox, unusual, even unbelievable, but could it truly be called illegal?

What courage does it take to allow yourself to be tested on camera before the eyes of your detractors? To reduce his wrist action and shoulder technique to a genetic anomaly would be to deny Murali's discipline and craftsmanship. Nature may have given him the advantage, but it is he who nurtured it, harnessed it and transformed it into magic.

|

|||

History has shown that mystery spinners rarely endure. Think of Bernard Bosanquet, Jack Iverson and our very own Ajantha Mendis. Once the mystery is solved, little is left. But even after 20 years the world never fully figured Murali out, despite the technology. And despite all the hostility, they weren't able to take him down.

Only time will tell how his legacy will endure. Unborn generations will examine old footage and marvel at how one era produced the two greatest spin bowlers in history. While arguments convince some of Warne's superiority, I have a suspicion the future may lie with the dark Tamil of supple wrist.

Warne took the existing armoury of legspin and turned it into something flawless. Murali took the dull weaponry of offspin and reinvented it as something lethal and mesmerising: he became perhaps the game's first wristspinning offie, but probably not its last. It is one thing to perfect an art, but another to create an art form.

For Sri Lankans, he will be the enduring proof that greatness is not beyond us; that brilliance can transcend race and overcome adversity; and that, if we focus our vision and build on our gifts, it is indeed possible to move worlds. And to do it quietly, with dignity, and with a grin.

Shehan Karunatilaka's novel, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew won the 2012 DSC Award for South Asian Literature