The box of tricks

|

|||

|

Related Links

In Focus:

Technology in cricket

Teams:

England

|

|||

When ESPN Star Sports, the ICC's global broadcast and production partner, announced that the 2011 World Cup would be watched by one billion viewers in every corner of the globe bar the Latin swathes of South America, it was a reminder that televised cricket is a rather different beast from the sport first screened by the BBC from Lord's and The Oval in 1938.

Back then, the public had Len Hutton's 364, a camera at one end and commentary of the kind that later provided fame for Mr Cholmondley-Warner, Harry Enfield's comic embodiment of Empire and the King's English. Now, the armchair viewers expect their cricket on a plate, with side helpings of Hawk-Eye, Hot-Spot and High Definition - all served up by accents ranging from Bumble's Accrington burr to Michael Holding's Jamaican lilt.

With its discrete vignettes - 540 of them in a day of 90 overs - cricket lends itself more comfortably to the microscope than any sport. And if a trip to the game promises mood, colour and a rewarding sense of the sport beyond the cut strip, then a stumble to the sofa may provide a more detailed insight.

In one sense, this is a matter of pure numbers. The 2011 World Cup was touted in advance as television's grandest cricket project yet. The pretournament publicity made an unabashed virtue of the sheer size of it all: 550 production-crew members at six outside-broadcast units (four in India, one each in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka) were expected to generate a total of 2,350 international and domestic flights, as well as 13,000 "room nights". There would be 27 cameras at each venue, not including the six required for Hawk- Eye. "The permutations," said Aarti Dabas, the ICC's media rights and broadcast manager, "are amazing." Presumably the expenses claims would hardly bear thinking about either.

When you consider that England's trip to West Indies in 1989-90, the first overseas tour broadcast live in the UK, was covered by seven cameras and a small crew including - in the words of the producer, Gary Franses - "only one guy, a freelance cameraman, who had ever done cricket before", the sense of an industry shedding its skin is palpable.

Cricket broadcasting's Rubicon was crossed that winter after the West Indies board - impecunious then as now - approached the sports agency IMG to sound out methods of cashing in on the world's most successful team. The answer, IMG suggested, was to display the talents of Viv Richards, Malcolm Marshall and Co on TV. This was less Baldrickian than it sounded, since Caribbean cricket had no tradition of regular or centralised coverage. (The footage of Colin Cowdrey's England taking advantage of Garry Sobers's declaration to win in Trinidad in 1967-68, for example, exists only because the local TV station had its act together at the time.) But the region as a whole lacked a broadcasting legacy. Coverage, therefore, was placed in the hands of Trans World International, IMG's TV arm, and - to the horror of MPs who swore by the sanctity of the BBC - the British rights were sold to Sky, then in its embryonic phase.

And while the BBC, whose coverage of the game had grown increasingly tired during its half-a-century monopoly, believed the Caribbean posed too many logistical pitfalls for a successful outside broadcast, Franses and his team picked up the gauntlet. When Graham Gooch's unfancied team pulled off a shock win in the First Test at Sabina Park, Sky - unaccustomed back then to covering major sporting events - did not have enough satellite dishes to go around. Without that first foray, the TV revolution may have taken a less precipitous course.

But the task of transmitting events in the Caribbean to fans back in the UK was not a straightforward one. For all the slickness of contemporary coverage, there was a needs-must air to proceedings. One of the commentators, the Middlesex and England left-arm spinner Phil Edmonds, was employed because he was on holiday in Jamaica at the time. Equipment was transported around the Caribbean in an ancient aeroplane by Carry Cargo, a West Indian company based in Miami, while facilities at the venues ranged from the non-existent to the rudimentary.

"The whole experience was terrifying," says Franses. "We didn't know what we were doing from one day to the next. We forever needed help designing commentary boxes. At the old Bourda ground in Georgetown, Guyana, there was a ditch around the perimeter and we had to place the camera on top of a moat. We had visions of it floating away."

The image captured the precariousness of the whole shebang. But progress was being made in other areas. By now, for example, viewers could watch the action from both ends - a gift from Kerry Packer, who was aghast that half the coverage had, until his World Series came along in 1977-78, been obscured by the batsman's backside. The BBC took a while to fall into line, arguing that one-ended coverage replicated the experience of the turnstiles customer, and it took another piece of Australian strong-arming to change their minds. When Channel 9 sent its own commentators to cover the 1985 Ashes in England, they told a reluctant BBC that unless they installed cameras at both ends, Channel 9 would do the job for them. Not wishing to be upstaged on home turf, the BBC took the hint. And if the physics of positioning a cameraman on scaffolding at the Nursery End at Lord's were occasionally challenged by the wind, a template had been set.

As British TV coverage of the sport entered a new competitive era that felt an age away from Peter West's avuncular summaries and fuzzy black-andwhite scorecards, the international game was going through a revolution of its own. Andrew Wildblood, now a vice-president at IMG and a central figure in the rise of the Indian Premier League, remembers the change of emphasis in the early 1990s. "When Gatting played that reverse-sweep in the 1987 World Cup final," he says, "it was broadcast by Doordarshan, the Indian state network. It looked as if the stroke had been played in snow.

"Then, in 1992, we signed the Indian board for $200,000. I remember sitting with Henry Blofeld, my travelling companion on that tour, and we were arguing with Jagmohan Dalmiya and I. S. Bindra over $25,000. That would barely buy you an over these days. But we got three Tests and five ODIs for the money, despite Doordarshan having a court case with the BCCI about coverage going to a foreign company."

The impasse - in an age when cricket was still coming to grips with globalisation - continued into the one-day Hero Cup, in November 1993, when the TWI production crew was informed by Indian police that, despite its purchase of the international rights for the tournament, it was breaking the law by treading on Doordarshan's toes. Negotiations continued while the crew's plane was sealed and impounded at Bombay airport; the competition's opening fixtures went untelevised until a deal was brokered.

Back in England, a bunfight was developing for slices of an increasingly mouth-watering pie. The summer after Sky's ground-breaking Caribbean broadcast had shaken a nation out of its belief that televised cricket meant perforce the BBC, the Benson & Hedges Cup final was televised by British Satellite Broadcasting - before it merged with Sky in November 1990 to form BSkyB. It was the first time a major county match had escaped the clutches of the terrestrial channels. Four years later, BSkyB bought the rights for England's home one-day internationals, and in 1999 Channel 4 entered the fray. BSkyB's share of the deal gave them one home Test a summer. The BBC were left with nothing. It was as if a member of royalty had been debagged.

It was around this time that cricket cottoned on to a truism that had previously been neglected. Gary Franses, by now at Sunset + Vine, who produced Channel 4's award-winning coverage, explains: "It's what you do in the 20 seconds between deliveries that makes the coverage, using the toys you have." If the BBC's toys had been largely limited to slow-motion replays, which in any case had been around since the 1960s, Channel 4 characteristically brought its outsider's eye to bear. "It was a wonderful contract to win," says Franses. "I'd been doing cricket for about ten years, so I knew who to get. The Channel 4 years were a World XI of TV cameramen and videotape experts. It wasn't hard. We just had to throw a bit more at it. The ECB, who by the late 1990s were fed up with the BBC, wanted innovation."

Rabbits had already been pulled from the hat. In 1995 TWI came up with Spin-Vision following Australia's tour of the Caribbean. Shane Warne would bequeath many legacies to the game, but here was his first televisual gift, a long lens that in effect shortened the length of the pitch and allowed viewers a close-up of his wristy repertoire. Gloriously, leggies and flippers were no longer dry abstractions. "Even Channel 9 agreed it was a good idea," says Franses in a nod to the industry's highly competitive nature.

But it was Channel 4 who introduced the British audience to the kind of wizardry we now take for granted. If the BBC's coverage had slipped into a clubhouse comfort in which a nudge or a wink could convey the necessary to a clique of well-informed viewers, Channel 4 went back to basics with their newcomer's zeal. And, crucially, they did so with Richie Benaud on board - cricket broadcasting's papal seal of approval.

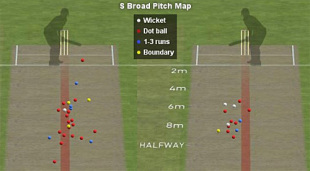

The Snickometer, the brainchild of Alan Plaskett, a computer scientist, was unveiled in 1999 and went some way - but not all of it - to settling debates about caught-behind decisions. Hawk-Eye, an ingenious computer system designed to track the path of the ball, was developed in time for the 2001 Lord's Test against Pakistan. It, along with its New Zealand cousin Virtual Eye, is now a fundamental, if occasionally controversial, part of the Decision Review System, and the generator of such team analysts' delights as the Beehive, which superimposes a bowler's grouping against an upright batsman. (Hot Spot, the infra-red imaging system used to capture points of impact, was first rolled out by Channel 9, and not until the 2006-07 Ashes.)

Other innovations were simpler, and perhaps more effective at spreading the gospel: if viewers were baffled by the concept of the doosra, the former Middlesex and Durham seamer Simon Hughes was on hand in a dark production van to explain all. As both The Analyst and begetter of Jargon- Busting, Hughes held the casual fan's hand in a manner that might have been regarded as a bit too touchy-feely by the BBC. Cricket was being democratised. The process continues, and it is necessarily imperfect. If the straight lines of tennis make the application of Hawk-Eye a relatively simple one, and the interaction between rugby's on-field referee and TV official has become clearcut, then cricket's many angles, perspectives and scenarios preclude complete precision. The issue of low catches, a perennial victim of foreshortening - the process by which a three-dimensional occurrence is rendered on a twodimensional screen - is a case in point.

But for the sheer breadth of possibilities, cricket remains a technician's dream. Plans for the 2011 World Cup included a movable "slips" camera, the better to capture the split-second reaction times required to field there, and a camera low down at 45 degrees from the batsman. The ESPN brainwave of crunching the screen to show the view from side-on as batsmen run between the wickets was set to continue.

Perhaps no gizmo has taken us closer to the game, however, than High Definition - or "HD" - television. Superior, for the time being, to the 3D experiment that received a lukewarm reception when it was trialled during a one-day international at Trent Bridge in 2010, HD has celebrated the little details we previously missed: the twist of the bat in the hand, the bend of the blade itself, the explosion of ball through turf and the beads of sweat on the forehead of the perspiring batsman. Where a regular camera offers 24 frames a second and the super slo-mo about 200-300, the 4-Sight camera used for HD coverage boasts 1,000.

Franses says TV has become the supreme arbiter. But if that is to the regret of some, then the sight of a batsman's eyes closing and lips pursing as he prepares to pull a bouncer heading for his grille has added the kind of drama Peter West and chums might only have dreamed about.