Norm O'Neill

|

|||

|

Related Links

News : Norm O'Neill dies aged 71

Miscellaneous : West Indies-Australia series awards named after Tied Test legends Cricketers of the year : Norm O'Neill Players/Officials:

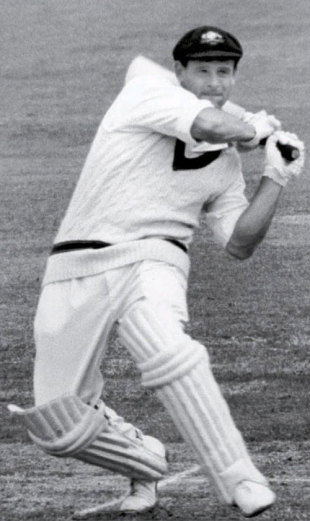

Norm O'Neill

Teams:

Australia

|

|||

O'NEILL, NORMAN CLIFFORD LOUIS, OAM, died on March 3, 2008, aged 71. The opening Test of the 1958-59 Ashes series, at Brisbane, was a comatose affair until the debutant Norm O'Neill batted after lunch on the fifth day; less than two hours and 71 exhilarating runs later, Australia sailed home by eight wickets, the fresh breeze of his vitality having blown away the torpor of the match. "A new star was on his way to join the cluster of the Southern Cross," wrote John Woodcock in The Times, and the balance of Ashes power - after three successive England series wins - was about to shift dramatically. O'Neill was the embodiment of that new era.

After being nurtured in one of the powerhouses of Sydney cricket, the St George club, he was picked for New South Wales at 18 and made a duck on debut, but the next season, 1956-57, his form was so exciting there was a clamour for his inclusion in the side that was to tour South Africa a year later. Left behind, he became the first batsman to pass 1,000 runs in a Sheffield Shield season since Don Bradman in 1939-40, his runs made with uninhibited power characterised by thunderous drives. His penchant for the hook and his desire to get on with the game made him difficult to contain, as the Victorians found to their cost when he made 233 in even time against them at Sydney, dominating a fourth-wicket stand of 325 with Brian Booth. Booth remembers that innings for the six successive fours which O'Neill hooked from bumpers hurled at him by Sam Loxton, and was awestruck by the power of his back-foot driving: "He was such a dynamic batsman."

O'Neill's technique, however, was fundamentally sound, even if he later gained a reputation as a nervous starter. Moreover, he was the complete cricket package: he was also New South Wales's leading bowler that year with 26 wickets from his quick leg-spinners (or, more usually, top-spinners). And there was his athletic fielding in the covers, marked by safe hands and a flat, powerful throw, which stemmed from his baseball background. He had been selected for the Australian side at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, where baseball was a demonstration sport, only to be ruled ineligible because of the widow's mite he had received in Sheffield Shield expenses.

Young, handsome, modest, multi-skilled - he had also been a champion schoolboy sprinter - O'Neill was an obvious candidate for hero-worship, as he seemed to offer a contrast to the timid and colourless character of much of the Test cricket of the 1950s. Thus some of the more impetuous scribes, including Bill O'Reilly, began to talk of him as "the new Bradman", which was to prove as much a millstone as it had been for Ian Craig a few years earlier. In fact, O'Neill was an original, and went beyond Bradman by mastering the subcontinent, hitting commanding Test centuries at Lahore, Bombay and Calcutta in 1959-60. In the helter-skelter of the Tied Test at Brisbane in 1960-61, he disciplined himself for nearly seven hours in making 181, an innings which gave Australia a small but crucial first-innings lead, and one in which Wes Hall was hooked savagely and safely. O'Neill was also at home in English conditions on the 1961 Ashes tour, hitting 1,981 runs at 60.03 overall. He finished the Test series with an exuberant 117 at The Oval, in which his footwork countered and crushed the spin of Tony Lock and David Allen, causing Wisden to describe him as "a sheer joy to watch" and name him as one of the Five Cricketers of the Year.

At this stage, O'Neill had made 1,722 runs at 53.81, including five centuries, in his first 23 Tests, but now a persistent knee injury affected his footwork and form, and that nervous-starter reputation began to attract even more media scrutiny: his final 19 Tests produced 1,057 runs at 36.44 with but a single hundred. In 1964, perhaps prematurely, he published an autobiography, Ins and Outs.

His final series was the tour of the West Indies early the following year. At Bridgetown, in what proved to be his last Test, he showed all his old confidence in making 51 and 74 not out. The Australians were united in their condemnation of Charlie Griffith's action, and in the Sydney Daily Mirror O'Neill described Griffith as "an obvious chucker", adding that "if he is allowed to continue throwing, he could kill someone". In London, the Daily Mail ignored an embargo on the syndicated publication of this material, so O'Neill found himself in breach of his contract by making a media comment before the tour ended. It was never clear whether it was these articles or a poor domestic start to the Ashes season of 1965- 66 that brought his Test career to an end.

In 1958, O'Neill had married Gwen Wallace, a gold medallist in the sprint relay at the 1954 Empire Games. In retirement, he sold cigarettes for Rothmans, who transferred him to Perth. There, his son Mark developed into a useful all-rounder, possessed of his father's attacking instincts as a batsman. Mark played for both Western Australia and New South Wales, and was appointed New Zealand's specialist batting coach in 2007.

Back in Sydney, Norm O'Neill was an informative radio commentator in the 1980s, but he spent the last decade of his life dealing with throat cancer. In 2003 he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for his services to cricket, an apt reminder of the pleasure which his freshness and star quality had given at a time when they were sorely needed. "He was as handsome as any film star and had great charisma," said his team-mate Alan Davidson. "Yet he was the most humble, modest bloke you could ever run into." And as his Australian team-mate and captain, Bob Simpson, put it: "If God gave me an hour to watch someone I'd seen in my life, I'd request Norm O'Neill. He just had that style."