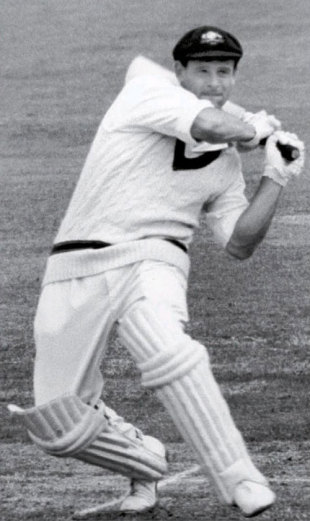

Norm O'Neill

| ||

Those who know Sydney, will perceive immediately that Glebe and Bexley are far-distant suburbs and they might well wonder how Mr. Campion played in one district while ostensibly living in another. Such happenings are not infrequent in Australian district cricket where friends are understandably anxious to play with other friends.

The point of this is that the young O'Neill, when seven, was always invited along to scout out for his uncle and a friend. The youngster's reward at the end of each practice session was ten minutes' batting -- with the pads on. Uncle insisted on the pads being worn, even though the young one could hardly move in them. Uncle, wisely, didn't want youthful confidence to be pricked by a nasty knock on an unprotected shin.

O'Neill began his schooling at the Bexley Primary school. Cricket here was of an indifferent nature, there being no competition against outside schools; the boys played among themselves. He moved to Kogarah Intermediate High School and came under an enthusiastic master, Mr. Fred Larcombe, whose main sporting interest was athletics.

He thought O'Neill had the makings of a champion sprinter but O'Neill was more interested in his cricket practices on Bexley Oval. His uncle now was insisting that O'Neill should always be over the ball, especially in back defence. He took him, too, to a big match at the Sydney Cricket Ground and the moment he saw Keith Miller he idolised him. He saw Miller make 66.

What impressed O'Neill most as the manner in which Miller hit the ball hard off the back foot. An interesting point, this, because O'Neill, in the writer's experience, uses a larger variety of strokes off the back foot than any other batsman.

As with so many other youngsters, Miller became O'Neill's hero. Nobody else could compare with him. The boy dreamed of his hero and he recounts how one day, in a class-room, he, O'Neill, was day-dreaming about playing in a Test match himself. He was on the verge of getting the run for his century when down came a ruler on his knuckles. The teacher, with O'Neill completely oblivious, had been standing over him for some minutes.

With the sound teaching of his uncle behind him, O'Neill moved on to Hurstville Oval, the district ground for the St. George club and scene of many brilliant deeds by Bradman, O'Reilly, Lindwall and Morris -- all St. George men. He made steady progress. He was getting plenty of cricket with his Kogarah school and once made 74. That night, supposed to be asleep, he heard his father ask his uncle: "Do you think he could become a good cricketer?" The uncle replied: "Yes, I think he could become very good indeed." O'Neill went to sleep a blissfully happy lad.

One day he batted in the St. George nets against Arthur Morris. Not even this genial man takes his bowling seriously. He used to walk two steps and then bowl up donkey-drops with plenty of spin on them. "He made a fool of me," relates O'Neill. But it was all experience and year by year the boy moved up the grade sides.

At 16, he came into the first grade side. The selectors, wisely, told him that no matter what happened, he was there for the season. He made 108 in seven innings. Next season, he was out 12 times l.b.w. in 15 innings. He was run out in the other three innings. This brought misgivings but he saw Harvey hit a brilliant near-double century against the South Africans and this inspired him for the next summer.

Analysing his failures, he thought it was because he tried to hit every ball to the fence. He decided this next summer to wait for them.

In the second game of the season, now aged 17, he got a century. He knew that all five state selectors were at the next match but he had no idea they had come to see him. He made a pleasing 28 -- and to his immense surprise found he was later chosen as twelfth man for the state side. He went on the southern tour, under the captaincy of his idol, Miller, and was chosen to play in Adelaide.

New South Wales had six of the South Australia side out for 49 when Miller threw O'Neill the ball. O'Neill thinks that Miller must have had the intention of bringing him into the game to dispel his nervousness. The local men took heart and runs from O'Neill's bowling, slow leg breaks, and hit 18 from three overs.

Miller had O'Neill number seven in the batting order but when Simpson, Burke and Saunders had made a big start, Miller changed his order and brought O'Neill up. He came in against a new ball and was clean bowled for none. O'Neill was finding his hero rather an unpredictable captain. He went out of the New South Wales side that season, but had gained some hard experience.

Next season, 1956, with the Australian players not back from England, O'Neill returned to Shield cricket and made 63 not out and 60 against Queensland. He held his place when the stars returned. Twice he failed against West Australia, but had a string of 60's against South Australia, Victoria and West Australia in the return game. He hit his first century against South Australia.

He was chosen for an Australian team to New Zealand, made 102 not out in the third and only unofficial Test in which he played, headed the tour averages at 72.66 -- but wasn't chosen for the tour of South Africa. This was one of the several incomprehensible non-selections by the Australians in this decade.

On figures, on promise, O'Neill richly earned that tour. He was very disappointed but gave the best possible answer. He made 1,005 runs at an average of 83.75. It was the first time 1,000 runs had been scored for New South Wales in a season. Bradman had done it for South Australia; Ponsford twice for Victoria.

Those who saw it will not forget his 233 against Victoria at Sydney in just over four hours, with thirty-eight 4's. The preceding Saturday he made 201 for his club and this was his first Shield double century and his fourth in the past five matches. O'Neill delighted in his rich stroke-play. S. Loxton had an impression the lad could not hook and plied him with an over of bouncers. O'Neill took four boundaries, all beautifully hooked. W.J. O'Reilly called him a second Bradman.

This great innings came at a time when O'Neill was having troubles with employment. He could get no time off for cricket practice and was coldly advised to start work at 6 a.m. to fit in practice. He arranged to go to South Australia, as Bradman did. Top New South Wales officials expressed regret, but said they could do nothing about it. Others did and O'Neill stayed with New South Wales.

O'Neill's first innings against Peter May's M.C.C. 1958-59 side proved his class. He hit 104 at Perth. He was the star of the match, attracting huge crowds to the practices that preceded it. He hit 84 not out for New South Wales against M.C.C.; had two failures for a Combined team but walked of right into the Test side.

His 71 not out in the second innings of the First Test at Brisbane saved a game that had been torturous for days. It was a brilliant piece of batsmanship. He hit 282 runs in the series at an average of 56, second to McDonald in both sides.

O'Neill was most popular in Pakistan and India in 1959-60 with his spectacular batting. This time he headed the Test batting, scoring 594 runs in eight matches, average 66, and hit three of his four tour centuries in the Tests.

The following season he hit three centuries against the West Indies, one for Australia, the others for New South Wales. So well did he score in the Tests that he finished second to Burge with 522 runs at an average of 52.

In this series, however, O'Neill often lost his wicket impulsively by sweeping to leg. He seemed, at this stage of his career, to be most conscious of his right-hand, allowing it to do most of the work. His bat was often swinging across the line of flight of the ball.

It did not take O'Neill long to pick up the pace and lift of English pitches. He made a brilliant century in the third game of the tour, against Yorkshire, at Bradford. There was nothing better than his strokes through the covers, suggesting he was keeping his right hand in its place. A big crowd at The Oval on the Saturday of the fourth game expected much of O'Neill but he fell to a sickening attempt to play a sweep shot.

He made a splendid 74 at Old Trafford and no better innings was seen in the whole summer than his 124 against Glamorgan at Cardiff. This innings had every conceivable stroke. He followed with 73 and 27 at Bristol and got 122 on his first appearance at Lord's, against M.C.C. He was carried from the field at Hove and it was thought he would be out for a long time but, amazingly, he was chosen to play in the first Test and made a very attractive 82.

O'Neill had to await the final Test before making his first century against England. He failed with one and nil at Lord's; 17 and 19 at Leeds, and 11 in the first innings at Old Trafford. Hereabouts, he was running into much criticism.

Few Test batsmen have had as severe an ordeal as O'Neill had in his first innings at Old Trafford. He was hit repeatedly on the legs and, once again, he had slipped from orthodoxy. This time, he was presenting such a bold face to the bowler that his right shoulder had turned appreciably and his swing, naturally, was across the ball.

O'Neill was given advice on that. He redeemed himself with 67, a fine effort, in the second innings; he hit a most brilliant 117 in the final Test at The Oval. He was just behind Lawry in the tour averages. Lawry scored 2,019 runs, average 61.18. O'Neill scored 1,981 runs, average 60.03. In the Tests, he averaged 40.

After a short tour of South Africa before an Australian season started, O'Neill so impressed W.R. Hammond that the old English Test star dubbed him the best all-round batsman he had seen since the war. That was high praise.

To be true, a high innings by O'Neill is a thing of masterful beauty. His stroking is delectable, immense in its power. But O'Neill has often got himself into a rut. He is a bad beginner. He seems to come to the middle as if he has been fretting in the dressing-room, worrying about the future. So, then, he often does something rash very early in an innings. He has had two slips from grace and only because he used his right hand too much, allowing a big gap between his hands on the handle, and then turning his right shoulder too much to the bowler.

If he can conquer himself for a start -- his rashness, his uneasiness -- O'Neill will not only have many more very big and thrilling scores (he's bound to have them) but he will have them more consistently. His rashness, too, often comes into his running between the wickets. For all that, he has given us some of the most glittering post-war innings. A glorious fieldsman, he has the dream throw.