John David Bannister

|

|||

|

Related Links

Players/Officials:

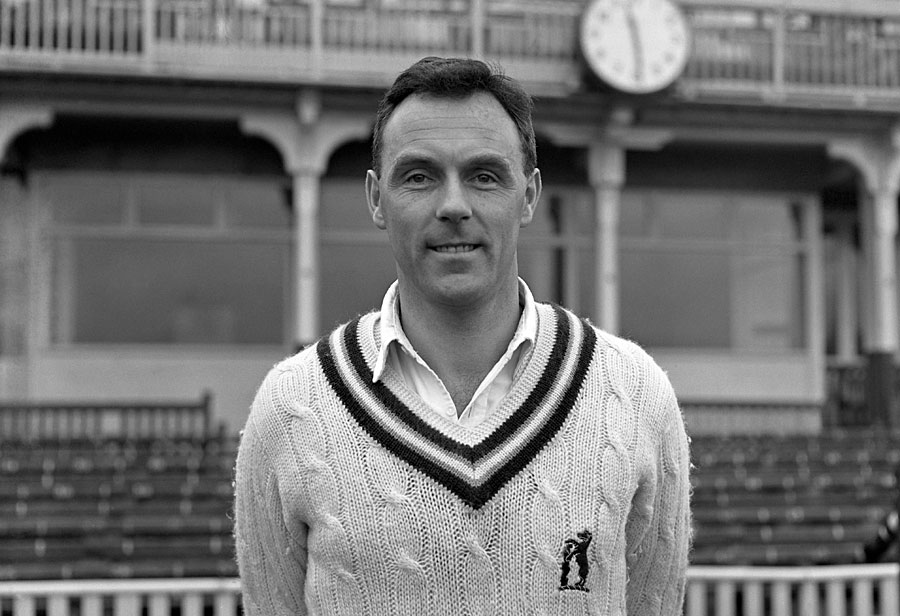

Jack Bannister

Teams:

Birmingham Bears

| Warwickshire

|

|||

BANNISTER, JOHN DAVID, died on January 23, aged 85. Long after he had retired from playing, Jack Bannister was sometimes described as the most powerful man in English cricket. He was the mainstay of the players' trade union - now the Professional Cricketers' Association - and later an influential journalist and broadcaster as well. And he performed important behind-the-scenes roles in the game's two great schisms in the 1970s and '80s - the Kerry Packer breakaway and the South African rebel tours.

"Don't talk to that man," one old-fashioned county captain advised his players. "He's a communist." Given the third strand of his life, that seems highly improbable: Bannister built up a chain of betting shops before selling them, and was always a committed and clever punter. The word "shrewd" clung to him in just about everything he did: bowling, betting, broadcasting and being bolshie (if not exactly Bolshevik). He was a great talker off-air as well: "Argumentative, belligerent and stubborn," summed up his daughter Elaine, "but that was all part of his charm."

His cricket career contained one sensational performance, still enshrined in Wisden: he took all ten for 41 in a Warwickshire friendly against a far-from-hopeless Combined Services team in 1959. (He was immediately dropped.) Bannister's other 1,188 wickets - all but for 17 for Warwickshire - were harder won, and often came upwind. "Jack was sharp," recalled team-mate David Brown, "and he was a proper seam bowler. Line and length were paramount to him, and he hated to see anyone do anything else.When he bowled together with Tom Cartwright, you could see the two patches where they had both landed the thing."

His boots were a particular source of wonder: "They were massive things. It wasn't that his feet were particularly large, it was just the boots. The soles would have been half an inch thick, and he'd knock metal spikes into them. The whiting got thicker and thicker. The laces went right up the shin. He had quite a high knee action, but how he lifted his feet no one knew." Bannister still had enough energy to nip off most evenings to the nearest greyhound track (most easily done in Taunton, where the dogs raced round the boundary).

He was a grammar-school boy with a mind that in another era might have taken him to a job in the City. Instead, towards the end of his career, he found part of his destiny in 1967 when his Warwickshire team-mates sent him to the first meeting of a putative body initially called the County Cricketers' Association. He was immediately elected treasurer, and became chairman a year later; after giving up cricket, he spent 19 years as secretary, and the strong-minded and well-funded PCA that exist 50 years on could never have happened without the persistence Bannister brought to the fledgling organisation.

"Jack was absolutely tireless," said his successor David Graveney. "The subscriptions were token, really, and there was no level of funding. But the game was Victorian in many of its attitudes. And Jack was willing to lobby whoever, however, whenever, to make people realise they had to join the modern world. Others later picked up the bat and ran with it. But he created the bat."

He also had great skills as a conciliator. When World Series Cricket split the game in 1977, both Bannister and the Association saw it as a grave threat to the members' interests. Dennis Amiss's decision to sign up was so contentious he was almost forced out of Warwickshire; Bannister helped patch up the wounds. When other players joined rebel tours in South Africa in the 1980s, his position was more equivocal: he had always enjoyed being there himself; he was a friend of the tours' organiser Ali Bacher, and strongly opposed to the boycott in that period when South African cricket had reformed, but the country had not. Those closest to the PCA say he steered a careful course.

By now, he had also become a high-profile commentator. Mike Blair, sports editor of the small but well-regarded Birmingham Post, had talked him into becoming its cricket reporter, and he took over as Wisden's Warwickshire correspondent, from 1983 to 2001. Though Bannister was more fluent as a talker than a writer, his knowledge and contacts served the paper and the Almanack well, and the job gave him a springboard into broadcasting. He broke through the glass ceiling that normally stops non-Test players becoming Test Match Special summarisers, then did the same in the TV commentary box, where his Brummie tones, analytical gifts and light touch made him a favourite.

His judgment was also respected in the press box. As one journalist explained: "If ever I had an off-the-wall thought, say that 200 all out on the first day was not as bad as it looked, I'd run the idea past Jack. If he didn't rubbish it instantly, I'd know I was on to something." He was also a lively, if erratic, raconteur. His anecdotes about his contemporaries were often brilliant and adorned Wisden obituaries for many years. He could sometimes go on a bit, especially when misjudging the interest level in his latest round of golf: "Watch out!" one pressman would whisper.

"He's in his when-I-got-to-the-fifth mood." Bannister loved betting every bit as much as golf and cricket, but he was not infallible: he said himself he usually lost his 30-year sequence of tipping contests with Richie Benaud (see Wisden 2016, page 194) and at the halfway stage of the 1983 World Cup final rashly offered 100/1 against an Indian victory. He also loved the companionship of cricket, but the game overrode all that: in notional retirement, he would sit at home in Brecon and do score flashes on big matches for Talksport radio. Neither he nor the station ever said he was at the game - but then again they never said he wasn't. Listeners might just have picked up a hint the day he cried out: "Bessie! Get off the sofa!"