How green is your sward?

|

|||

Cricket's global administrators do love a board meeting, all mahogany chairs, glass tables and endless supplies of upmarket coffee. There is much to discuss, after all. Dollars. Participation. TV deals. Future tours. Behaviour. Match- fixing. Governance. But something is missing, something that more than 97% of climate scientists agree on - from NASA to the Geological Society of London, and the nearly 200 countries who signed the Paris Agreement in December 2015. Climate change is real, and it is extremely likely to be man-made. In July 2016, NASA reported that January to June had been the hottest on record for each respective month, part of a trend in which almost every year since 2000 has been hotter than the last. In November, Danish and US researchers found that air temperatures above the Arctic were an astonishing 20˚C warmer than expected.

The Arctic Resilience Report warned that the melting of the ice cap risks triggering "19 tipping points", which could cause uncontrollable change worldwide. The bad news just kept on rolling. Cricket, like everything else, will be fundamentally affected. And yet, despite all the warnings, the ICC have done almost nothing. By the end of 2016 they had not commented publicly on climate change or the challenges it presents to the game, nor outlined a grand plan. They are keen to stress that action is on the agenda, but have done little in terms of mitigation (reducing emissions) or adaptation to a changing world. They set no environmental targets for their members. They do not currently employ a sustainability officer.

And while their laudable social responsibility work with UNICEF is detailed on their website, there is no reference to the environment. Tours are arranged on a distinctly ungreen basis, with no pressure on members to plan a lower-impact itinerary. England's winter series in India, for instance, included a mishmash of cross-country flights, when the whole thing could have been done in a more sustainable circle. The ICC offices are in Dubai, which relies on energy-intensive air-conditioning and desalinated water.

Those offices are, to give the ICC their due, undergoing an environmental audit, with the aim of becoming carbon neutral. But, in the words of communications officer Claire Furlong, progress has "historically been a little ad hoc". The men (and it is still predominantly men) who run the game are not scientists or activists: they're often ex-players, sometimes businessmen. They are juggling huge budgets, balancing television deals with the need to proselytise. No one pretends it is easy. As Gideon Haigh has written, the role of administrators has traditionally been to "inure cricket against change rather than to enact it". Perhaps they are not worried about the climate, or don't see the urgency, or are too busy. But prudent businessmen always look to the future.

Shortly after the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States last November, 300 American businesses wrote an open letter, urging him not to pull out of the Paris deal. These were not lentil-weaving anti-capitalists: 72 of the companies had an annual revenue of over $100m. But climate change is beginning to bite. "We want the US economy to be energy-efficient and powered by low-carbon energy," they wrote. "Failure to build a low-carbon economy puts American prosperity at risk." As Barack Obama put it: "We are the first generation to feel the effect of climate change, and the last generation who can do something about it."

Many sporting organisations are lagging behind business in recognising the threat, despite the fact they will be significantly affected. Cricket has plenty to lose. It also has a moral responsibility to act. If you put to one side winter and water activities, there are few sports more intrinsically connected with their environment than cricket. Of all the major pitch games, it will be hardest hit by climate change. From barren refugee camps to the ice of St Moritz, from the ochre Australian outback to the windswept Scottish coast, cricket is defined almost entirely by the conditions. If they change, so does the essence of the game.

That is truest of all in Britain, land of Blake's pleasant pastures, the menacing cloud from across the moors, the Hove sea fret, the misty morning in the Quantocks. Here, there has been a tendency among writers and players of all abilities to romanticise the greensward, to link cricket with the pastoral and the pre-industrial. Yet there is a looming danger: traditional English conditions could be gone in 20 years. MCC's Russell Seymour is the UK's only cricket sustainability manager, having been in the job since 2009, and he is more than worried.

"A match can be changed fundamentally with a simple change in the weather," he says. "In the morning, sunny conditions make batting easier, because the bowlers can't get any movement in the warm, dry air. Cloud cover after lunch increases humidity, and the ball starts to move. After a shower, conditions change again. Now imagine what happens with climate change. There will be alterations to soil-moisture levels, and higher temperatures will bring drier air, then drier pitches. This will bring a change to grass germination and growth, which in turn affects the pitch and outfield."

In other words, the assumptions we make about English cricket, its landscapes and rhythms, will no longer apply. The ball may not move in 2025 the way it did in 1985, or even during that holy summer of 2005. The oldfashioned English seamer could be on his last legs. Then there's rain. According to data from the Met Office there is more of it, and the increase is continuing. Because of the complexity of the weather system, it is unclear how things will pan out. Indeed, the UK Climate Projections (2009) show an increased likelihood of drier summers. Experts do agree that more extreme weather events are likely, along with wetter, warmer winters and more intense summer downpours. The ECB won't release precise data on how much cricket has been lost to rain over the last ten years. But, according to Dan Musson, their national participation manager, it is considerable.

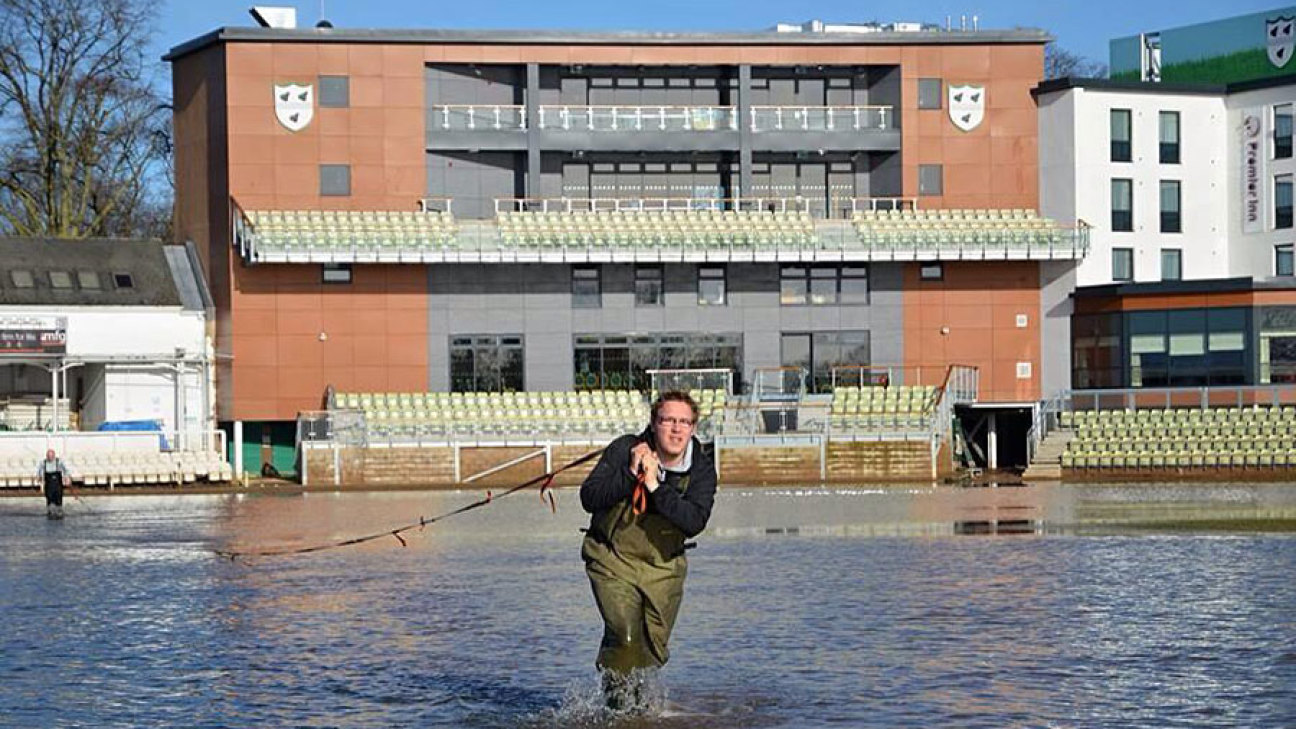

"There is clear evidence that climate change has had a huge impact on the game in the form of general wet weather and extreme weather events," he says "I've been at the ECB since 2006 and we have had to implement flood relief efforts on half a dozen occasions, both in season - particularly in 2007, with flooding in the Midlands and the Thames Valley - and out of season, when winter storms Desmond and Eva ran through the north of England in December 2015. Wet weather has caused a significant loss of fixtures every year in the last five at recreational level, and posed challenges to the professional game."

The recreational game is most at risk: clubs have fewer resources to protect against the threat, and more difficulty with insurance. And because the land on floodplains is usually cheap and fertile, that's where many municipal grounds can be found. Games are repeatedly called off; people eventually give up and do something else. At grassroots level, the ECB have made good progress. They have commissioned research from Cranfield University to identify flood risk, and produced guidance for clubs; and they run a smallgrants scheme to fund wet-weather management and preventative measures. In 2016, more than £1m was doled out to flooded clubs, which are also encouraged to install solar panels, recycle rainwater and look after their equipment: to think green in order to reduce costs, and survive. A further £1.6m has been set aside for 2017.

But for the first-class counties there is not yet an overarching strategy, nor much guidance. Individual clubs are taking action, but no one can name the greenest county, as there is no central data. Clubs that should be audited for climate risk, and making sustainable development part of every decision, are doing neither.

And yet, given money and encouragement, there are so many possibilities. Could counties reduce the travel footprint of players and spectators? Could there be rebates for fans who use public transport? Could clubs integrate sustainability into procurement and purchasing policy? Can they avoid singleuse plastics? How do they use water? What food are they providing? Can they buy from ethical suppliers? If they are rebuilding, are they using sustainable materials? Can they generate renewable electricity? Offset carbon? Educate fans? Leave a positive legacy? One Planet Living, the blueprint for London 2012's environmental approach, gives practical guidance.

Nudging organisations to change their behaviour requires carrot as well as stick. Positive action could be rewarded by the ECB, whether financially or in terms of match allocation. The benefits of thinking long-term also need to be spelled out: central investment in drainage, for example, has meant counties can get back on the pitch after bad weather far sooner than previously. On paper, the ECB have committed to action. Their 2016 strategy document, Cricket Unleashed, says: "We will work to promote environmental sustainability throughout the game. We recognise our role in society and the natural landscape, and will work on reducing our impact on the environment."

It's vague, but it's there. The ECB are already a member of BASIS (the British Association for Sustainable Sport, founded by Russell Seymour), and there are those at Lord's who are impatient to change: a steering group have been formed to engage with the professional game, and make good the promises in the document. Whereas efforts from interested ECB employees have foundered further up the ladder, there is now more optimism. It is a golden opportunity for those at the top to be bold. There are three international tournaments coming up in England - the Champions Trophy and the women's World Cup in 2017, and the men's World Cup in 2019. The ECB's steering group hope to use the first two as pilot schemes, then gain ISO 20121 certification for the 2019 World Cup. It is the minimum they should be doing. ISO 20121 is an international standard for sustainability in event management inspired by the London Olympics and Paralympics, and since certified for the French Open tennis at Roland Garros, football's 2016 European Championships, and the Rio Olympics.

Other sports have started to change their behaviour. The north American National Hockey League, uniquely among sporting leagues, produce a sustainability report, and all the commissioners of the major US sports have made statements on the environment and climate change. Unlike in the UK, the French government are encouraging sustainability through sport. Golf, cricket's fuddy-duddy cousin, is being pushed by the R&A and the Golf Environment organisation. FIFA, despite major governance issues, have embraced sustainability around the World Cup. Sailing is well ahead of cricket, too.

Could English cricket step forward to take the international lead? Be progressive! Innovative! Principled! The ECB need only look over their shoulder: in February 2017, MCC announced they would buy electricity generated solely from renewable sources. To millennials and post-millennials, climate change is no global conspiracy, but a living, breathing, terrifying threat. They are looking for action - and organisations who put their head in the sand will be scorned. Sport communicates passionately, and reaches the parts governments or NGOs cannot. Cricket can positively influence fan behaviour by example, and win back the trust of those disillusioned by the raging giant of unbridled commercialism.

On their rocky outpost in the north Atlantic, the British are protected to some extent by wealth and geography. But other cricket nations are in the front line. In 2016, the IPL was forced to relocate matches from Maharashtra because of a water shortage. Bangladesh is what the World Bank calls a "potential impact hotspot," threatened by "extreme river floods, more intense tropical cyclones, rising sea levels and very high temperatures". Sri Lanka and West Indies are also vulnerable to rising sea levels. Rainfall patterns in Zimbabwe are ever more uncertain. The southern part of Australia is projected to have more extreme droughts.

Yes, there are ways to manage the environment. Qatar is even working on technology that cools open-air arenas, and cricket has experimented with enclosed stadiums. But is that really the future it wants? We must either accept fundamental changes to the game, or alter how we behave if we are to maintain, as far as possible, what we have. No one is pretending cricket can change the world. But it can set a moral tone and show a concern for the environment that has nurtured and shaped it over hundreds of years. Do nothing, and it has everything to lose.