In Surrey's service

He may have played just four Tests but Robin Jackman was an ever-present stalwart for his county through the 1970s

Steven Lynch

12-Dec-2012

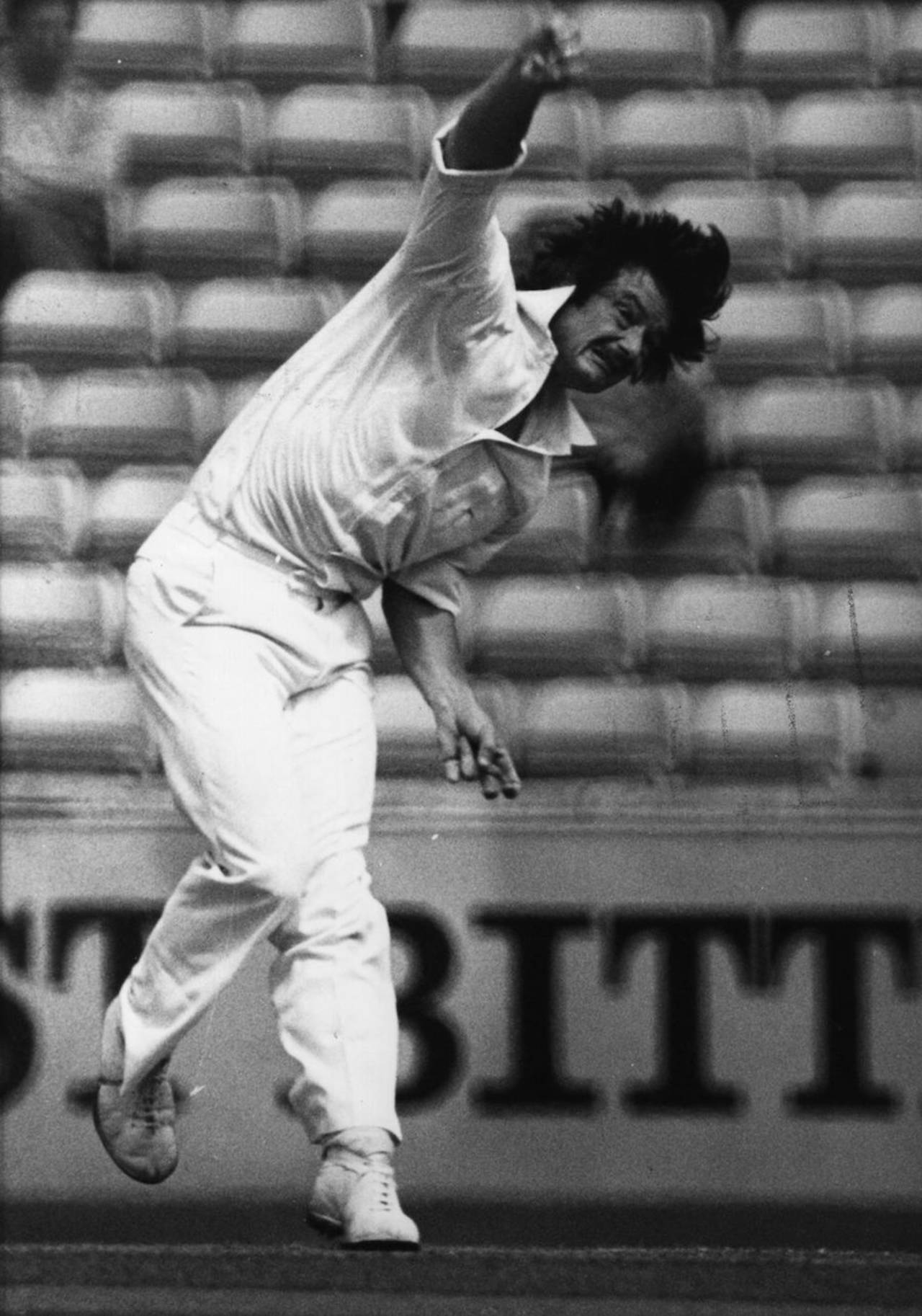

Jackers: whole-hearted • Getty Images

I spent a lot of time at The Oval while growing up - too much time, some said, when they looked at my exam results. As a junior Surrey member it was exciting to be able to swan into the pavilion, even into the Long Room bar, although back then I was confined to the end presided over by the impressively buxom woman whose unchanging cry was, "I only do tea and coffee - no drinks."

Outside it always seemed to be overcast, and if Surrey were in the field either Intikhab Alam or Pat Pocock would be bowling from the pavilion end. Inti, a whirl of rubbery arms as he delivered another puzzling legbreak or googly, seemed always to be smiling; but Pocock wasn't far behind in the laughter stakes. His own action seemed impossibly dainty, back leg flicking outwards as he bowled.

And, in my memory, puttering away almost unchanged from the Vauxhall End was Robin Jackman. He was just below top pace, his legs seemingly shorter than the rest of his body suggested they should be. He trundled in, sent down a ball that tested the batsman's technique... and probably appealed. I reckon Jackman probably holds the career record for most appeals per over: about 2.5 per six balls.

It wasn't just me who was impressed by these whole-hearted displays. Alan Gibson, the whimsical writer whose reports for the Times were often more about his battles with train services than the match he was supposed to be watching, tagged Jackman the "Shoreditch Sparrow", mainly on account of those chirping appeals. It was a good name, although it suggested a Cockney background, which was some way from the truth: Jackman was born in India, while his father was serving in the Army there, and his relatives included the suave comedy actor Patrick Cargill. Around the time Jackman's county career started in earnest, his uncle was starring in the TV sitcom Father, Dear Father, as the absent-minded dad of two high-spirited blonde daughters: one imagines Robin's popularity in the dressing room would have been cemented if he ever persuaded them to visit The Oval. Jackman once told Cargill he wanted to be an actor too, only to be firmly advised "Don't."

For years it seemed that Jackers would be nothing more than a consistent county performer: England recognition seemed a step too far. By 1978, he had never taken 100 wickets in a season, but the following year he managed 93 at an average of 17, then in 1980 - in his mid-thirties - sailed into three figures for the first time, ending up with 121 at 15.40. The selectors could ignore him no longer, and Jackman was included in the XII for the showpiece Centenary Test against Australia at Lord's at the end of the season. It is hard to imagine a selection more popular on the county circuit (or in the Oval Long Room bar).

However, being in the squad is no guarantee of playing... as Jackman found out when he reported to the team hotel. Back then the 12th man would stay with the Test team for the first two days before returning home for his county's match on the Saturday. And when he booked in, Jackman was understandably deflated when the receptionist said: "Ah yes, you're only with us for three nights, aren't you?" He knew then he wouldn't be playing, although he wasn't officially told until just before the start. It would have been nice, he wrote later with characteristic humour, to "have been informed by someone a little closer to the cricketing network, albeit not nearly so attractive".

He was just below top pace, his legs seemingly shorter than the rest of his body suggested they should be. He trundled in, sent down a ball that tested the batsman's technique... and probably appealed

Jackman was not initially required for that winter's tour of the West Indies either, but was called up when Bob Willis was injured. He arrived at Lord's to get his instructions on a bitterly cold day in February 1981, only to be buttonholed by photographers wanting a snap of England's new (or new-ish: he was 35 by then) recruit. I was working at Lord's then, and when he wanted some cricket gear to lend authenticity to the photos, handed over some of mine, which was kept in the office for winter nets. I proudly informed my club colleagues next day that our sweater was in the Daily Mail, probably the nearest any of us would ever get to an official England tour.

That minor kerfuffle was followed by a much bigger one when he got to the Caribbean. Jackman had strong links with South Africa - he had played a lot there, and his wife was from Cape Town - and the hard-line government in Guyana objected to his presence. The Test there was called off, and only high-level diplomatic discussion rescued the whole tour.

Jackman finally did make his Test debut shortly afterwards, in Barbados. He made a fine start, with the wickets of Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes, and later added Clive Lloyd. There were three more Test caps, a tour of Australia in 1982-83, and 15 ODI appearances too. He probably really wasn't quite quick enough for Test cricket, but few could have tried harder: no one (except possibly the odd man on the Georgetown omnibus) begrudged him those belated moments in the international sun.

After retirement, Jackman settled back in South Africa and became an amiable TV commentator. A month or two ago came the news that he was battling cancer - completing an unpleasant treble with Tony Greig, another hero of mine from the 1970s, and a later favourite, Martin Crowe. Good wishes go to all of them: it goes without saying that Jackers will fight with all the energy he displayed during those long spells for Surrey. "If anybody could find a way of bottling Jackman's energy, zest and full-hearted commitment," wrote Pat Pocock, "then the future of cricket would be safe for the next century."

Steven Lynch is the editor of the Wisden Guide to International Cricket 2012