Finding family in your cricket brethren

Whether you're a homeless refugee or just a young person in need of guidance, your cricket team can often act as place to roost

Nicholas Hogg

05-Sep-2016

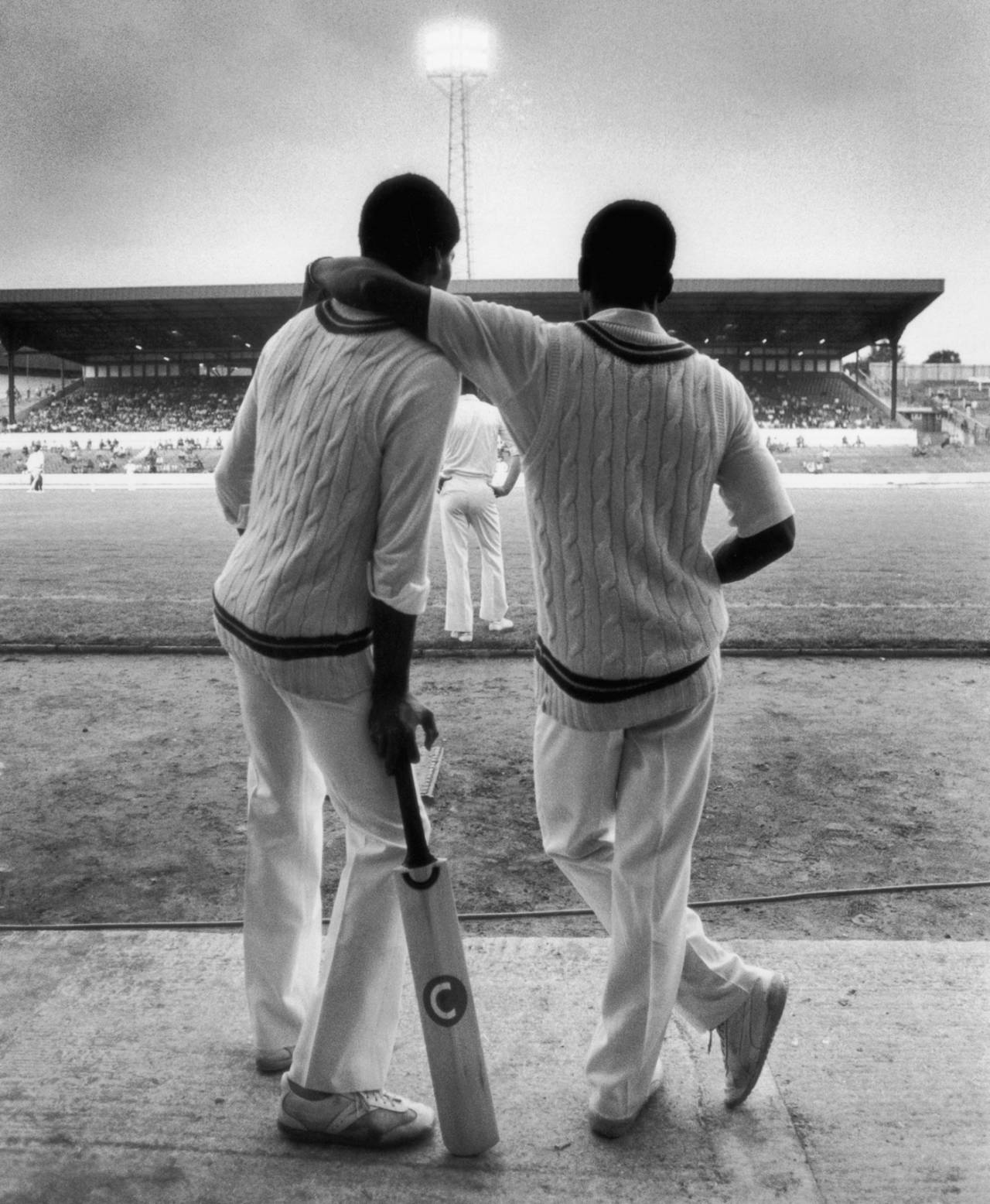

A cricket team can be like a home away from home • Getty Images

Despite not having played a true home game since the 2009 militant attacks on the Sri Lanka tour bus in Lahore, the Pakistan team proudly tops the ICC Test rankings. Misbah-ul-Haq, captain of this nomadic cricket nation, fittingly said that being No. 1 "is not a destination, but part of a journey". His players see their family and friends a few times a year. Considering the homesickness problems of some of England's best, Pakistan's mighty achievement has come under physical, logistical and psychological stress.

Cricket and home, or a lack of one, is a concept I was introduced to at the tender age of 17. Saturday afternoon, picked for a league game with my old Leicestershire club, Barkby United, I left my house in the morning, walked off my estate and carried my kitbag across the cornfields to the pretty little village ground I'd been playing on since I was 11. We played the match, win or lose I can't remember, and I hiked back across the fields to my house. Or what I thought was my house. My stepfather ensured that I never walked through the door again, and instead of my own bed I slept that night in the park, wearing my whites over the top of my clothes to keep warm.

The next morning I sought out the man I usually called upon for advice - my captain. He might not have guessed that his sage words from mid-off on my outswingers would result in me turning up on his doorstep without a home. However - and long before the #CricketFamily hashtag on Twitter - he welcomed me into his house. I stayed for a month before our opening batsman moved out of his flat so I could move in.

And the cricket family wasn't just about a roof over my head. At 17, with no guidance, no curfew, no one telling me not to get blind drunk or go clubbing every night of the week, the players became surrogate fathers. I played to impress my team-mates, the cricket collective that watched over not just how I performed on a Saturday afternoon but whether I was eating properly, and whether I was still turning up to college on a Monday morning.

All across the country, anywhere in the world, I hope, where cricket is played, a thriving club is a force for good in a society that feels more and more fractured. A healthy team, whether directly or indirectly, imbues values and codes of behaviour, and gives back to the individual in times of need.

Afghan refugees in Germany playing cricket pose for a squad photo•Getty Images

So perhaps it's no surprise that the Refugee Cricket Project (RCP), a specialist programme established in South London by the Refugee Council's Children's Section in response to the number of teenage boys, particularly those from Afghanistan who were passionate about cricket, exists. Staff working with the children observed how playing cricket boosted their language learning and confidence, and also helped introduce them to British life. The RCP offers year-round cricket coaching, fixtures against a host of opposition, including the MCC and my own team, the Authors XI, as well as placements within local club sides. It also provides advice and support for members on immigration and welfare issues.

For boys fleeing a war-torn country, evading threats from political groups, imprisonment, and even forced recruitment into terrorism, cricket has become a safe space. After making long and dangerous journeys through alien cultures, and then arriving in a land where their only friends are their fellow migrants, cricket is a home away from home, and the support of team-mates is akin to the comfort of a family.

Refugees at the Jungle Camp in Calais, where some of the players who are now part of the RCP once stayed, put on nightly cricket matches that apparently baffle the local French police. "The games are particularly enjoyed by the young Afghan players," reported the Daily Mail, "who used to face punishment if caught playing cricket by the Taliban."

A love for cricket, it appears, transcends war and conflict. Even Harold Pinter, Nobel prize-winning playwright and keen social cricketer, famously ran back into a burning house during the blitz. "There was an air raid. We opened the door and our garden, with this large lilac tree, was alight all along the back wall. We were evacuated straight away. Though not before I took my cricket bat."

In the two matches I've played against the RCP XI, it's not only the raw talent that dazzles, the athletic fielding, lightning bowling and outrageous batting, but the empathy and warmth within the squad and its wider organisation. To take part in a competitive game - facing the quickest of quicks I've seen (or perhaps "not seen" would be more accurate) - versus such gracious opposition is a rare pleasure. The cultural exchange in playing against a side of young refugees goes both ways, and can only enhance our understanding of the much vilified "other" in a UK riven by anti-immigrant rhetoric. This is a team bonding not only through a shared experience of trauma and diaspora, but a love of sport. This is cricket family.

Nicholas Hogg is a co-founder of the Authors Cricket Club. His third novel, TOKYO, is out now. @nicholas_hogg