Mike Brearley turns 71 this week, an age that barely seems possible for English cricket's benign eminence grise; where do the years go? But then he was 34 when he first played for England in 1976, 39 when he assumed the captaincy a second time for the immortal

Headingley Test match of 1981, and his career to that point felt like one from another age. From 1961 until 1968, from undergraduate to postgraduate, he played for Cambridge University while acquiring a first in Classics and a 2:1 in Moral Sciences, as well as turning out for Middlesex and touring a couple of times with MCC. He managed to slip in a couple of years of lecturing in Philosophy at the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, and then became captain of Middlesex in 1971, leading them to four County Championship titles. On his retirement in 1983 he took to psychotherapy and a life that has kept him on the edges of the game.

A rare presence on television and with no more than an occasional byline in the papers, Brearley has done his ageing elsewhere. He remains trapped in the mind's eye as his younger self, crouching at first slip with his hands cupped in front of him, his Leviathan Botham to his right at second, and that other grey-haired sprite Bob Taylor to his left in the gloves.

Brearley was a terrific slip catcher, a legacy of his early days as a wicketkeeper, and from there he could watch his bowlers. His batting was a different matter, and there was something moving about watching him open for England because he was almost always outgunned. A Test average of 22 told no lies, and his periodic half-centuries were islands of respite as he fought against the tide.

Self-awareness in such circumstances can be a curse, and he certainly didn't want for that. He was strong off his legs through midwicket and forced well off the back foot to point and cover, but he was deeply vulnerable to high-class pace bowling and there was plenty of it around. He often seemed to be squared up, his bottom hand coming off the bat as the ball flew to slip, and he would soon be back in his familiar position on the balcony, feet up on the rail, a newspaper on his knee and a gimlet eye on the game.

His invention of the first helmet, a home-made skull-cap with odd little ear flaps poking out from under his sunhat, was typical of a mind always searching for advantage, and we can see it now as a pivotal moment, a bold move that changed batting (and quick bowling) forever. He more than anyone would have appreciated the psychological rather than the physical shift the helmet made possible.

Throughout, he married learning to intuition. Captaincy, he found, had a "zone", that legendary plateau ascended to at rare times of peak performance. Ed Smith wrote a lovely piece for ESPNcricinfo last year

about a talk Brearley gave on the subject, in which he described a game for Middlesex against Nottinghamshire on a fast wicket. The great South African allrounder Clive Rice was at the crease when Brearley had a lucid vision of him carving the ball to a fly-slip position, a feeling so powerful that he felt as though he was inside Rice's mind as he played the shot. Brearley duly set the field, and Rice did exactly that.

It's an insight into how a modest player exerted such a grip on men of much greater ability, but Brearley had more than just a deep imagination and Rod Hogg's famous "degree in people" in his armoury. He saw the world in a joined-up way and brought that broad external perspective to the game, yet not every side of him was public.

Mark Ramprakash, who was around the Middlesex dressing room as a youngster soon after Brearley had left it, remembers that he was more than capable of handing out an old-fashioned bollocking, especially with his old sparring partner Phil Edmonds in the other corner. Edmonds was said to have sometimes returned to his mark backwards to make sure that Brearley hadn't changed his field while he wasn't looking.

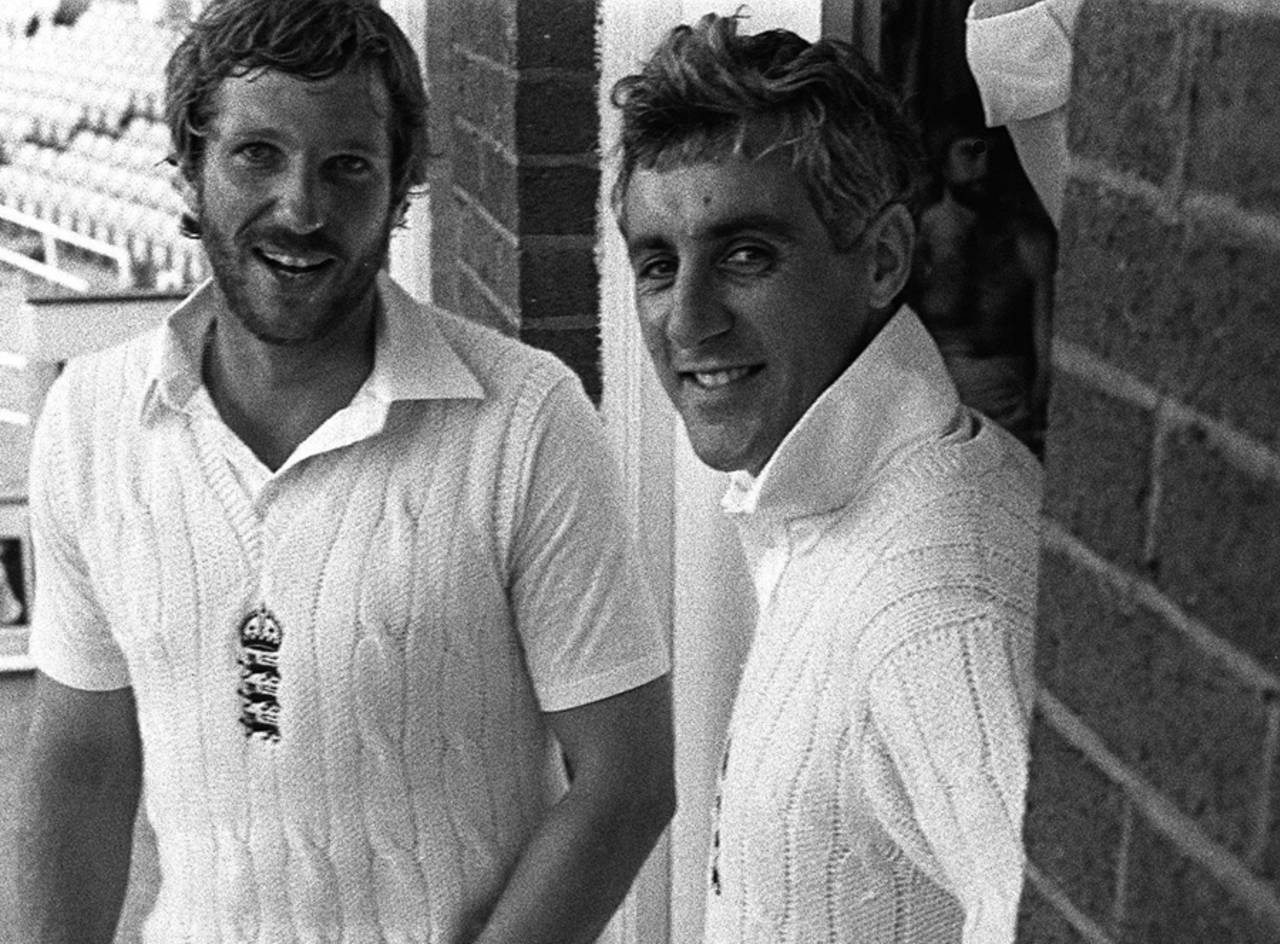

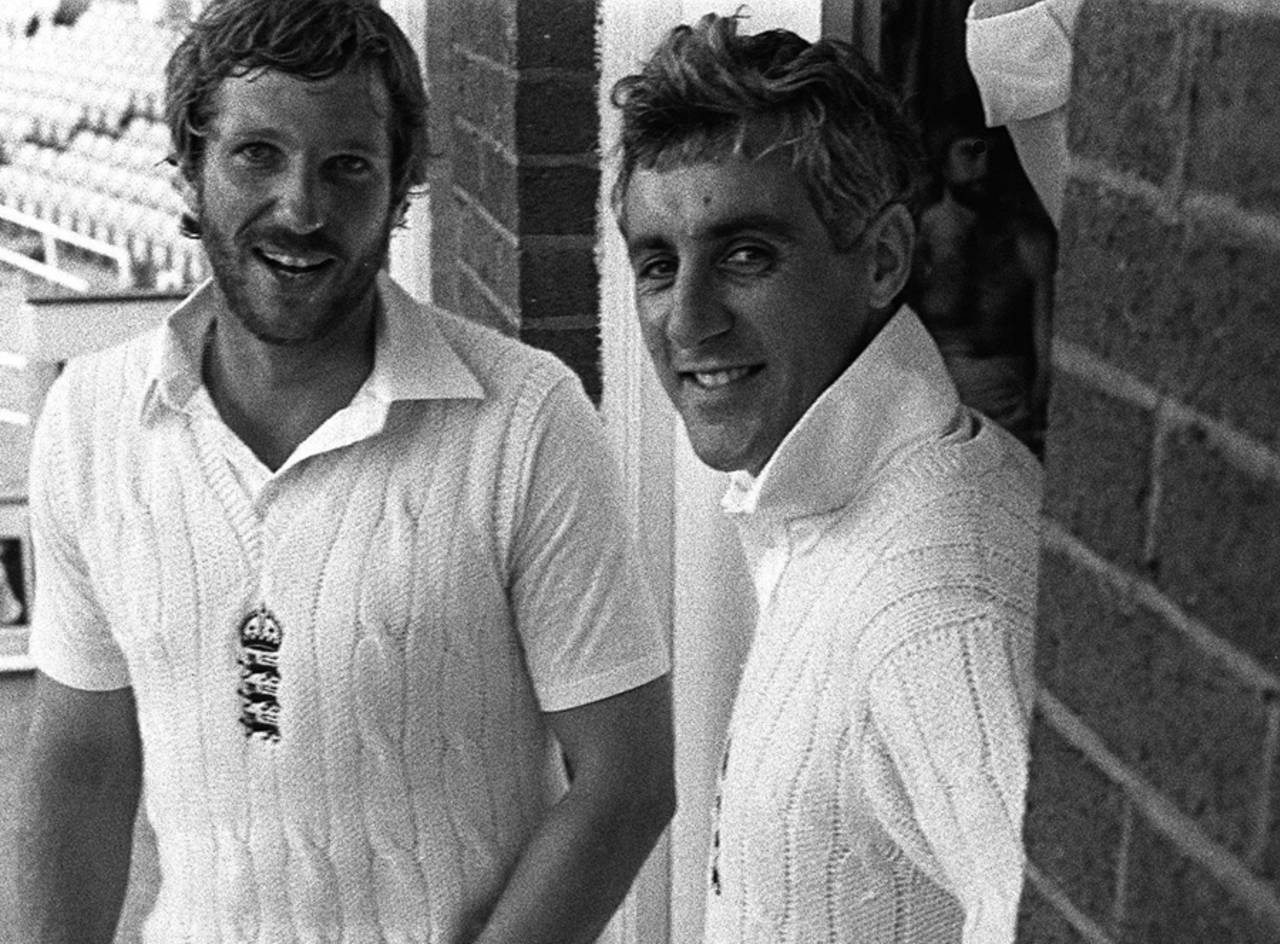

Like Jardine, it's for his captaincy that he will be remembered (that's harsher on Jardine's batting than it is on Brearley's: he averaged 48 in Test match cricket), and within that, for 1981 and for Headingley. What he actually did remains a glorious mystery. "To some indefinable extent, I think I was able to combine with Botham," he said. Sometimes just being there is enough.

On retirement, he wrote The Art of Captaincy, its title perhaps a sly allusion to The Art of War, and it's hard to question his choice of adjective because if captaincy was not regarded as an art before Brearley, it was after he had gone. He left just the lightest of touches, but it was sure enough to endure. Happy birthday, skipper.

Jon Hotten blogs here and tweets here