Always the hero

Gloucestershire's folk hero embodied the dash and splendour of a more gracious age

Frank Keating

17-Dec-2008

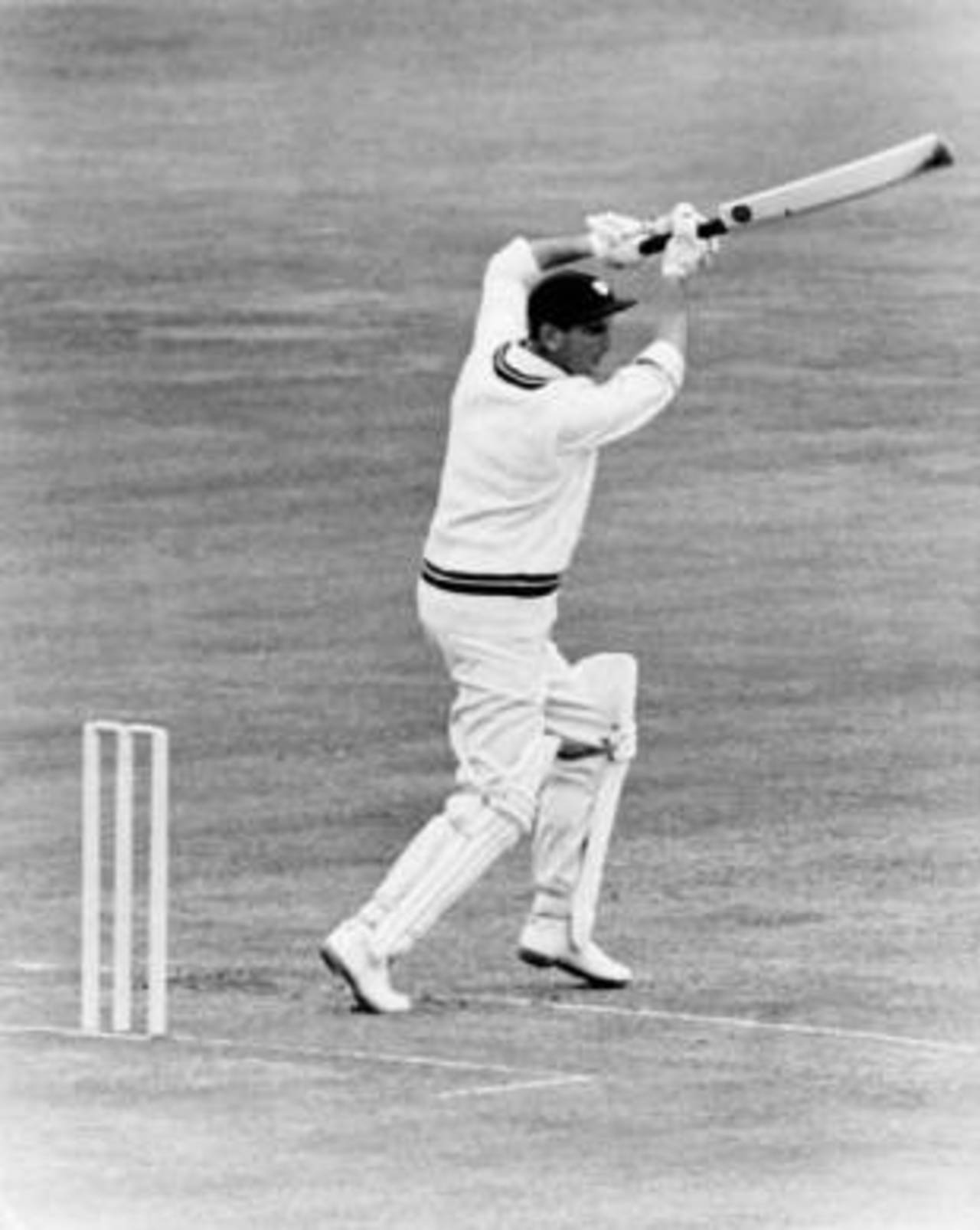

At Lord's during his 153 against Pakistan in 1962 • PA Photos

The first time is always the best - and for romantics anyway, as the years roll on, the first remains the most enduringly gratifying for mind and spirit. I talk, of course, of hero worship. Recollection warms the memory as well, for you are seldom betrayed by the figure you first lionised in the uncomplicated purity of early childhood. In my case, I am even more fortunate - my boyhood's callow, idol worship has grown into a fond and comradely relationship. When I was 12, Tom Graveney was ten years older and already a champion folk hero of Gloucestershire in England's pastoral and cuddly west country. Now he is 76 and I talk to him as a contemporary. And my hair is greyer even than his. Yet I am still in schoolboy awe of the valorous chivalry of his deeds at cricket, of the genuine creative invention and artistry of his batsmanship.

Gloucestershire, of course, had a noble heritage in batsmanship. It was the county of WG Grace, and of Gilbert Jessop and Walter Hammond too. Once a midsummer, the cricketers would travel north into the blissful hills to play two or three championship matches in the stately town of Cheltenham. This visit would be the season's high-temperature mark for us local urchins.

August 1950 held the most red-hot two days of my sheltered life till then, when the county gathered to play the mesmerising West Indian tourists at Cheltenham. Of course, our fellows were skittled soon by the ravenous and magical guiles of Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine. The only one to play the two with any degree of certainty was "our Tom" - fresh country boy's hale face, coltishly upright and gangly shy at the crease, but with a high, twirly backlift and a stirring signature flourish in the follow-through of his trademark cover-drive. A man sitting sardined on the grass next to me in the rapt throng said: "Our Tom'll be servin' England within a twelvemonth, you'll see."

And so he was, and so we did. He was blooded for one Test against the South Africans in 1951, at Old Trafford on a sticky, and he stayed in for nearly an hour to make 15 ("full of cultured promise", said John Arlott on the wireless). That October he left for his first overseas MCC tour to take in the new sights, sounds, and differing surfaces of "All India". He scored warm-up centuries at Lahore and Karachi but missed the first Test match, in Delhi, with a severe bash of dysentery. After a week in hospital he was still uneasily queasy when the second Test came along, in Bombay.

More than half a century on, he remembers: "I reckon I felt and looked like a skeleton when I walked in to bat." He took a pint of water and a salt tablet every half-hour, which turned into an awful lot of water and salt - because he endured for eight hours in the fierce heat against the craft and cunning of Lala Amarnath, Sadu Shinde and Vinoo Mankad. His epic 175 was the highest Test score by an Englishman in India, until Dennis Amiss made 179 in 1976.

Us hero worshippers continued to raise the rafters back in Gloucestershire as Tom served England with grace and charm for the next ten years - matching first the elderly monarchs, Len Hutton and Denis Compton, stroke for stroke, then the two lordly and haughty amateurs, Peter May and Colin Cowdrey. By which time a group of dullard "industrial" selectors at Lord's became grudging. This Graveney, they said, was all very well, but, horrors, he treats Test cricket like festival cricket; his manner is too carefree, his strokeplay too genial, that he only seeks to present his great ability rather than enforce it ruthlessly. So England dropped him for three years and Tom moved across the border to play for Worcester, where the mellow architecture of his glorious strokeplay matched the resplendence of the ancient cathedral.

The batsmanship of Our Tom was of the orchard rather than the forest, blossom susceptible to frost but breathing in the sunshine. Taking enjoyment as it came, he gave enjoyment which still warms the winters of memory

He continued to enchant all England every summer, but not the Test team. Till, in 1966, another string of sad England performances had the selectors seeing sense and turning, once again, to Graveney, now 40, to pull them out of a deep hole dug by Garry Sobers' West Indians. At Lord's, too. Tom answered the ferocity of Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith with a majestic 96, then 109 in the following Test, and an even more regal 165 in the fifth, at The Oval. He was back, and all cricket was under the spell of his masterclasses.

The following summer, against India at Lord's, Graveney unrolled another masterpiece - 151 against Chandra, Bedi, and Prasanna. In the New Year honours list of 1968, the Queen awarded him the OBE and he celebrated with a sublime 118 against West Indies in Port-of-Spain - his personal favourite century. The following year, Graveney's 105 against Pakistan in Karachi rounded off the enchanted odyssey.

The hero still lives in Cheltenham, where it all began. We still take a beer together, and I sit at his feet and listen, rapt again as the schoolboy was. Content and smiling, still hale and hail-fellow, Tom has had both hips replaced, but still plays regular golf and keenly follows his beloved cricket (he thinks modern bats far too heavy - "only a tiny minority, a Lara or a Tendulkar, can use them as we did; like a rapier, a wand").

When he retired from the crease in his mid-40s, the wise old cricket writer JM Kilburn hurrahed Graveney's approach: "In an age preoccupied by accountancy, he has given the game warmth and colour and inspiration far beyond the tally of the scorebook."

Precisely. The batsmanship of Our Tom, was of the orchard rather than the forest, blossom susceptible to frost but breathing in the sunshine. Taking enjoyment as it came, he gave enjoyment which still warms the winters of memory. Still the hero.

Frank Keating wrote on cricket and other sports for the Guardian for close to 30 years before his retirement in 2002. This article was first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine