The case for fear

With no fear of decapitation to conquer, how can a cricketer be truly brave?

Christian Ryan

24-Dec-2009

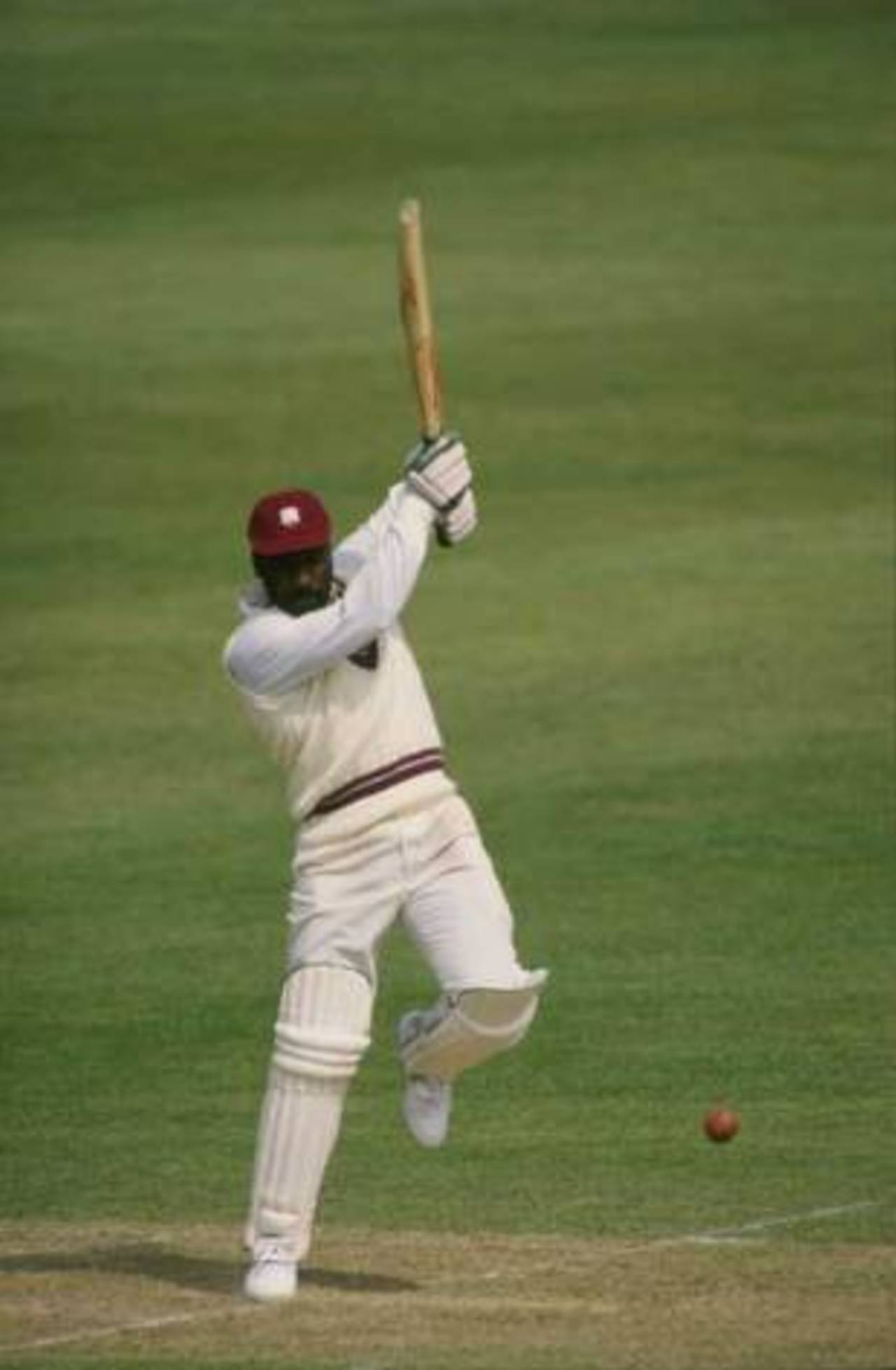

No helmet, no problem: Viv Richards demonstrates how it's done • Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

At Hays Paddock the other evening, the last Friday before Christmas, Kew's under-16s played Boroondara's under-16s. A creek gurgled, wildflowers grew, a dozen dog-walkers and their dogs went round and round. You had to peer closely for it to hit you that this was not the tranquil escape from the world that it seemed - helmets, three of them, on the heads of the boys in the middle.

Helmets? How strange. They played 21 overs a side. From start till stumps, the two batsmen plus the wicketkeeper wore blue helmets with white titanium bars across their faces, except when one of the batsmen was wearing a green helmet with white bars.

Kew batted first. Their score spluttered along, in bursts and silences, the most popular stroke a sort of shovel-sweep in a tight arc between mid-on and midwicket. After a while Boroondara's wicketkeeper, feeling clammy, extricated his head from the blue lid and white bars and barked advice at a couple of fielders. This was between overs. Then play resumed and the helmet went back on, even though the bowler, a smiley little fellow, was lobbing up full-pitched, looping straight-breaks that seldom beat the bat. After 21 overs the total was 6 for 114. Total hits on helmets? Zero.

In reply, Boroondara's batsmen began nervously - though not, as far as could be discerned from beyond the yellow boundary cones, because they feared possible brain damage or death. Balls in the second, sixth, ninth, 11th and 14th overs reared as high as the boys' bellybuttons. One ball jumped rib-high; one nearly neck-high. Another, released by a red-cheeked lad with a stutter at the top of his run-up, almost brushed a batsman's breastbone. The batsman, not noticeably terrified, took a giant swipe at it. At no stage was there any hint that heads might roll. Helmets nevertheless stayed rooted to skulls.

The boys of Hays Paddock punch one another's batting gloves and bowl a slower ball per over and generally take their lead from the men of Australia's Test team, who were at that moment stuck in tense struggle with West Indies on the other end of the continent. Marcus North and Brad Haddin were facing Sulieman Benn, a slow bowler, and they were wearing helmets, helmets with little bars across their faces.

At some juncture - and it happened so quietly that no one noticed - cricketers began donning helmets not so much to protect their heads, but out of habit.

Viv Richards, the last cricketer in Test history who could have worn a helmet and chose not to, ever, is now the last loud anti-helmet campaigner. Once, long ago, Viv said this: "[When you] cover a young cricketer in all kinds of padding and put him in to bat on a perfectly predictable pitch, there is no way he is going to develop the same degree of skill."

Viv was at it again recently, bewailing "all that King Arthur stuff" in an interview with Kevin Mitchell. The Guardian's Mike Selvey, cricket's wisest speaker of straight-out commonsense, called Viv mischievous, which was mischievous of Selvey, for Viv is not some jealous ex-champ foaming behind corporate-box perspex and drinking himself blotto over lunch. On this issue Viv is passionate and consistent. He expressed himself most eloquently in his second autobiography, Hitting Across the Line, in 1991, a time when metal and bars was still an unusual sight on 15-year-old heads. If we'd listened to Viv then, perhaps we'd be playing a different game now.

What Viv put forward was simply this: a case for fear. Growing up on diabolical Antiguan pitches, dressed in homemade cardboard pads, gave Viv the urge to play the hook shot. "To get rid of the thing." Being helmetless made him aware of danger, yes, but it also made him aggressive, instinctive, it made him feel brave, and out of this bravery was born confidence and the feeling that he, not the bowler, was the one in control. The helmet age knows no such dance between courage and fear. That dazzling tension has been struck out. Now, a bowler cannot maim a man. And with no fear - fear of decapitation - to conquer, how can a batsman be considered truly brave? "With the removal of that fear," said Viv, "a certain amount of excitement has gone."

Being helmetless made Richards aware of danger, yes, but it also made him aggressive, instinctive, it made him feel brave, and out of this bravery was born confidence and the feeling that he, not the bowler, was the one in control. The helmet age knows no such dance between courage and fear. That dazzling tension has been struck out

Eighteen years on, who'd dare pronounce the Master Blaster wrong? Helmets were supposed to embolden modern batsmen to hook balls off their eyeballs - the most exotic page in the textbook. Instead they mostly lurch on to the front foot, knowing no bouncer can scone them, breaking Bradman's Art of Cricket mantra about an initial back-foot movement being the best movement. And planting your weight on your front foot, your left shoulder tilting towards mid-off, is no place from which to attempt a hook shot.

Back when Viv's SS Jumbo was doing his talking for him, there was an incentive to hook bouncers to the fence: it might persuade the bowler to desist from aiming balls at your head. Not much urgent call for that now. Ensconced behind metal, batsmen prefer to weave and duck and wait for the percentage shot: drives, nudges, dainty little flicks. Inzamam-ul-Haq, Chris Gayle, Younis Khan and Virender Sehwag (twice) have erected Test triple-hundreds containing not one hooked four or six, according to Cricinfo's ball-by-ball commentaries.

If that sounds dreary, it has coincided with the world's pace stocks shrinking and the cricket ball apparently ceasing swinging - which, actually, might not be such a big coincidence. All those Haydenesque strides down the wicket leave bowlers 18 not 22 yards in which to swing it.

And another thing: it is hard to see people's faces, with everyone behind bars. Nothing can get in. And not much peeps out.

More exciting? Not a bit.

Get rid of them? "Foolhardy," says Selvey, "and very probably illegal under health and safety regulations."

But the players don't all wear helmets in Australian Rules, the rugbys or professional boxing, do they?

Probably things have gone too far for any kind of formal banning of helmets. It may not be too late for a gentle change in cricket culture. Hardest to convince might be the parents of small boys. Back at Hays Paddock, where not a hook stroke was seen, an incident took place near the end of Boroondara's failed run chase. At least an incident seemed to take place. No one could be sure. For there was no concern or commotion, and the fielders returned instantly to their positions. But there was a noise, a soft thud, and it looked like the batsman got caught in a front-foot tangle, and the ball, which was not particularly short or fast, appeared to rap his white titanium bars, low down.

Without his helmet on, the boy might have stepped back and hooked a six. Or he could have got a cut lip. Either way it would be something to see. And, as Viv has taught us, the boy with the cut lip would probably become a better cricketer.

Christian Ryan is a writer based in Melbourne. He is the author of Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket