A man of destiny

Despite the anticipated turbulence ahead, supporters of Younis Khan can take comfort that their hero is sitting pretty

Saad Shafqat

25-Feb-2013

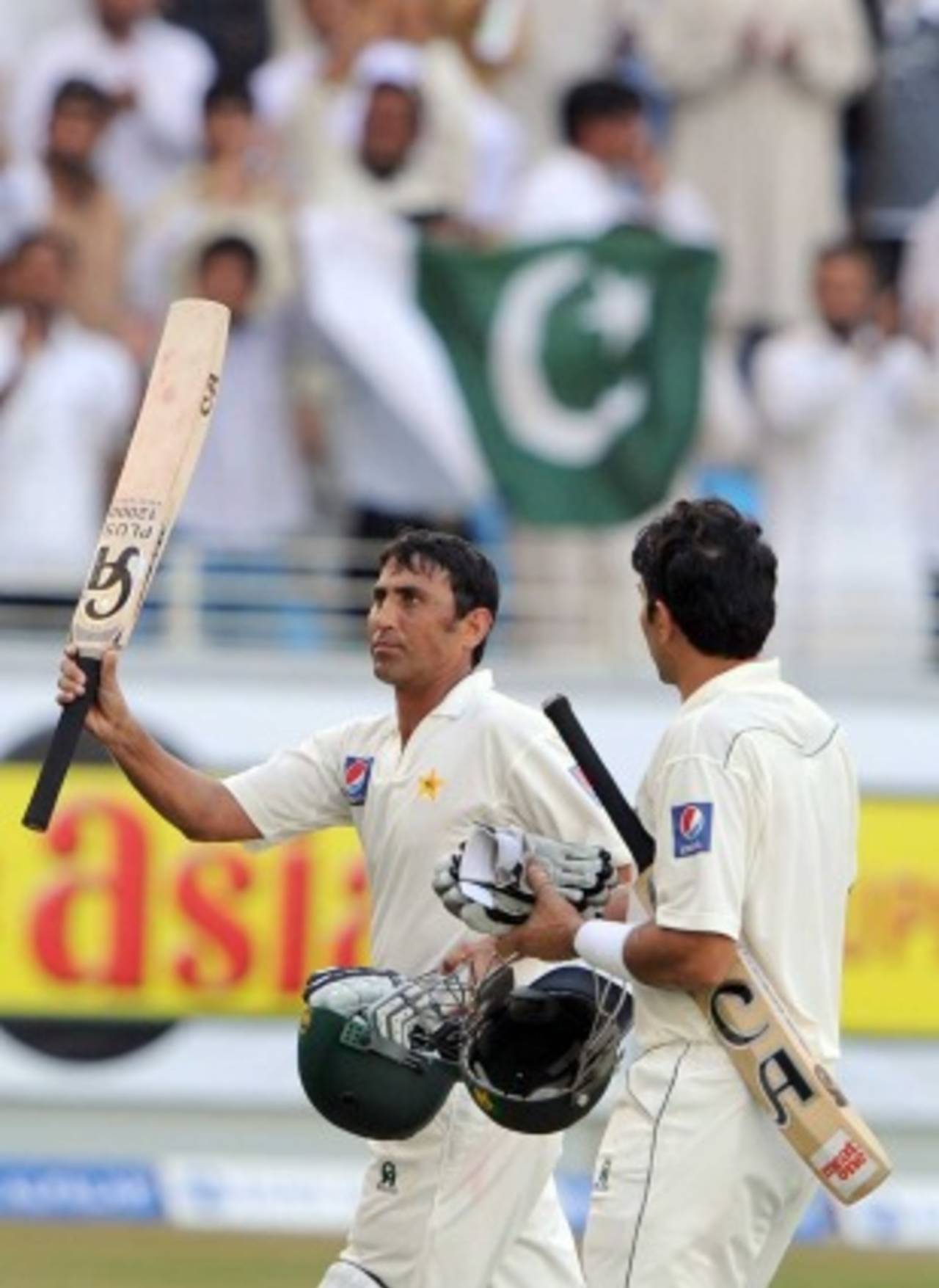

"Younis Khan convinced everyone of his unbending personal moral fibre" • AFP

Even though he made a century on Test debut, it took a while for fans to warm up to Younis Khan. His technique seemed casual, even careless. Each delivery was eyed for a boundary, he was vulnerable to swing with far too many edges, his bat was too far in front on the forward defensive, and there was more bottom hand in his drives than the unwritten standards of Asia’s batting aesthetic would allow.

Despite that inaugural hundred, his average after his first 12 innings in Test cricket was only 21.25, and on more than half of those occasions he had been dismissed in single digits. Yet he was a heavy scorer on the domestic circuit, and the selectors persisted. His brass tacks, take-it-or-leave-it manner also won him a following.

Then came a string of overseas hundreds – in Sri Lanka, New Zealand, and Bangladesh, and against West Indies in Sharjah – and he more or less settled into the No. 3 spot, promising to heal one of Pakistan’s long-standing ulcers. Nevertheless, his erratic form continued. In the spring of 2005, when Younis met India in a Test for the first time, he had played 32 matches and his average was still less than 40.

That series revealed much about the man, not just to the public, but possibly also to himself. The first Test in Mohali saw him dismissed for 9 and 1, including the embarrassment of getting castled while shouldering arms. He was also off-key in the field and ended the game completely out of sorts. The press dismissed him, and Pakistan’s own team management vilified him.

The first true sign of his greatness as a batsman was that this mounting anger and hurt willed him into excellence. After 147 in the next Test at Kolkata, which Pakistan lost, he went to Bangalore, and scored 267 and 84 to become Man of the Match and square the series. The performance set Younis apart and demonstrated the enormous promise and possibilities of his career as a fighter, capable of batting his team out of trouble.

If you talk to Rashid Latif, the former Pakistan wicketkeeper and captain, who mentored Younis like a younger brother, the fulfilment of Younis’s heroic destiny was never in doubt. Younis came under Latif’s wings at the Malir Gymkahana, a sports club in one of Karachi’s middle-class suburbs. He impressed everyone with his untiring work ethic and his ceaseless devotion to every aspect of the game. “Younis never missed a match,” recalled Latif, when I spoke to him on the phone recently. “This may not sound like much, but in the context of Karachi in those difficult days, it told me a great deal about him.”

The point is subtle, but important. In the mid-1990s, when Younis was cutting his cricketing teeth, parts of Karachi were an ethnic war zone. The city's majority Urdu-speaking community was at loggerheads with the Pathans, who hailed from Pakistan’s north-west frontier. Younis, an unmistakable Pathan, would brave gang fights and flying bullets through some of Karachi’s most troubled areas, to be schooled by his teacher Latif, a celebrated Urdu-speaking son of Karachi, in a relationship that had the makings of an epic. Imagine a portentous Catholic-Protestant collaboration in Belfast during the height of the Irish trouble, or a black-white partnership in Soweto during the darkest days of apartheid, and you’ll get some idea.

Today Younis is a 64-Test veteran with 17 centuries and a 50-plus average. Aged 33, this puts him within striking distance of Pakistan’s most hallowed batting records. Already he has threatened Pakistan’s highest Test innings, 337 by Hanif Mohammad, with a triple-hundred in Karachi in 2009. Pakistan’s highest Test aggregate (8832 by Javed Miandad) and highest number of Test hundreds (25 by Inzamam-ul-Haq) are also in his line of fire.

He has a reputation for fearlessness – squaring his shoulders to any attack, straightening up after any blow, never shying from a verbal or psychological joust, and never hiding behind a nightwatchman. He has also convinced everyone of his unbending personal moral fibre. This magnificent inner strength enabled him to lead Pakistan to a Twenty20 world title mere weeks after terrorists had shattered the national cricket ethos with an attack on the visiting Sri Lankans in Lahore. It also allowed him to wait out the recent tense duel with PCB chief Ijaz Butt, until the lesser man finally blinked.

Many observers feel that Younis Khan also happens to be the most capable and deserving candidate for Pakistan’s Test captaincy. His record as captain (one win, five draws, and three losses) may not be noteworthy on paper, but he has leadership stature and, unlike other potential contenders (including the current captain Misbah-ul-Haq), is an automatic selection in the side. Most importantly, with the Pakistan team ensnared in a spot-fixing scandal, Younis stands firm as the only frontline player utterly untouched by this cancer. This might have had something to do with his unceremonious ouster from the captaincy following the disastrous summer tour to Sri Lanka last year – which would constitute a very good reason to put him back in the saddle now.

The terrible wrinkle is that Younis is on the wrong side of the current PCB administration, and these thoughts are moot until a new set-up comes in. The way things work in Pakistan, that could happen tomorrow, or not for another couple of years. Despite the anticipated turbulence ahead, supporters of Younis can take comfort that their hero is sitting pretty. Great things happen to men of destiny. Younis may be on the wrong side of the PCB, but he is not on the wrong side of history.

Saad Shafqat is a writer based in Karachi