Old and flawed, still adored

Stephen Chalke

|

|||

|

Related Links

Teams:

Birmingham Bears

| Derbyshire

| Durham

| Essex

| Glamorgan

| Gloucestershire

| Hampshire

| Kent

| Lancashire

| Leicestershire

| Marylebone Cricket Club

| Middlesex

| Northamptonshire

| Nottinghamshire

| Somerset

| Surrey

| Sussex

| Warwickshire

| Worcestershire

| Yorkshire

|

|||

Too many teams, too many matches, too few spectators, an unsatisfactory points system - all these things have been said about the County Championship through most of its 125-year history. Yet against all the odds the competition has repeatedly found ways to survive, a Victorian creation at the heart of English cricket in the 21st century.

Before its formalisation, the Championship was no more than a construct of the newspapers and cricket publications. They introduced the word "champions", and took to printing tables that varied according to their individual system for ordering the teams, differing sometimes even on which games counted. In 1886, most publications had unbeaten Nottinghamshire as champions, but the magazine Cricket, by including matches against the touring Australians, had Surrey in first place. Was it coincidence that its editor, Charles Alcock, was secretary at The Oval?

The August Bank Holiday of 1887 saw Surrey at home to Nottinghamshire, and the game attracted the greatest crowd English cricket had ever seen: 27,000 on the Monday. Some were unruly, with Alcock at one point picking up a man and throwing him back into the crowd, but one thing was clear: the contest to be champion county had captured the public imagination.

Alcock was a pivotal figure in both cricket and football. At The Oval he staged the first football internationals, and the first home Tests against Australia, and he created the FA Cup, modelling it on a tournament he had played as a pupil at Harrow. Many in Victorian England sought to maintain the amateur ideal of playing sport for recreation only. Hockey outlawed not only payment but any form of competition - "pot-hunting" as they called it. In cricket, it was the same for the club game in the south, where this philosophy lasted until the late 1960s.

The powerful Club Cricket Conference, founded in 1915, made it a condition of membership that "no club shall be connected with any organised cricket league or competition". Alcock took a different view. He overcame opposition to allow professional clubs to enter the FA Cup; in cricket, Surrey - in contrast to the other southern counties - fielded XIs that were predominantly professional.

In 1888, the year in which 12 professional clubs in the North and Midlands created the Football League, the eight leading counties formed a Cricket Council, under the chairmanship of Kent's Lord Harris, to come up with a similar structure. In December 1889 they reached agreement, and the Championship began its formal life the following May. At the end of the first year, the Council voted to introduce second and third divisions, with promotion and relegation, but this proved controversial.

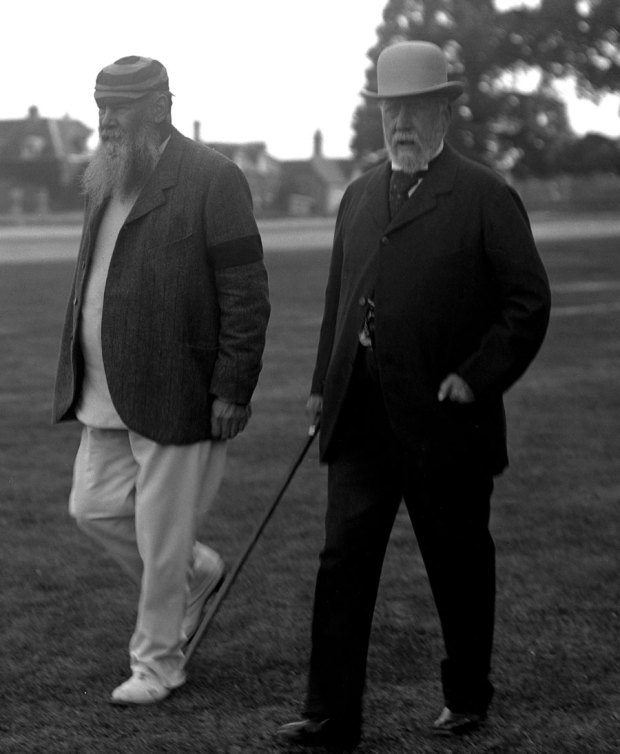

A second meeting, attended by the Minor Counties, ended with a decision to suspend the Council. MCC assumed responsibility for the Championship. The eight counties were the "Big Six" of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Nottinghamshire in the North, and Middlesex, Surrey and Kent in the South, along with Sussex, the oldest county club, and W. G. Grace's Gloucestershire.

They were joined in the second year by Somerset, and from 1892 to 1894 the nine counties played each other home and away - or "home and home", as they called it. It was clean and simple. The Championship had its detractors. In 1893 the magazine Cricket Field, fearing that it was leading to "unmitigated professionalism", called for its abolition: "It is only counties able to dispense with the assistance of gentlemen that can stand the strain of a full first-class campaign, and even from a spectacular point of view this is a consummation not to be desired." But The Times in 1896 was closer to capturing the national mood: Cricket has never been more popular than it is now, and for much of this popularity the skilled county teams in their keen competition for the Championship are responsible. A dozen years ago the visit of an Australian eleven had something like a monopoly of general interest. But times have changed. County cricket is the thing, and no extraneous element can endanger it.

Such was the Championship's popularity that other counties wanted to join. In 1895, five more had been admitted - Derbyshire, Essex, Hampshire, Leicestershire and Warwickshire - and at this point the structure became complicated. Yorkshire and Surrey, each of whom could call on a large pool of professionals, were happy to play twice against all the other counties, a total of 26 three-day games in four months, but this was well beyond the means of Somerset and Essex, even Middlesex, whose best amateurs could not give up so much time.

The result was a system in which counties organised their own fixtures. Some arranged 26, others 12 or 14. Always they faced their opponents home and away, and it was the strong sides whom everybody wanted to play, as they attracted more spectators. Middlesex, for instance, did not agree to meet Warwickshire until 1912, the year after they became the first of the newcomers to win the Championship.

|

|||

Already some voices were warning there were too many teams, yet in 1899 Worcestershire, with a half-built pavilion and substantial debts, gained admission by persuading six counties to play them home and away. They were followed in 1905 by Northamptonshire. By now several teams were surviving on large donations from local benefactors. Two such were Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, both of whom might have withdrawn from the competition had the 1915 season not been cancelled. The war turned out to be a financial blessing: they had little expenditure, and many members loyally continued to pay their subscriptions.

Who was eligible to play for a county? That had been cleared up back in 1873, when tighter regulations put an end to men playing for two, even three counties in the same season. But by the 1900s concern was growing that some teams, in their eagerness to win, were abusing the rules by importing "colonial cricketers" and paying them a retainer while they completed their two-year qualification. "The one object of the County Championship," wrote The Times, "is to see which county can produce the best cricketers, and not which can purchase the best cricketers. Under the present system a millionaire with a hobby for cricket could make Rutland the champion county in about four years' time, and there need not be a Rutland man in the winning eleven."

In 1919, the counties, unsure of themselves after four years of war, opted for a reduced Championship, with matches played over two long days. The crowds, starved of entertainment, flooded back, and all was well for a while. In 1921, during this post-war euphoria, Glamorgan talked their way in. A year earlier, there was nearly a controversy over the method of determining the champions. At the start of their final matches of the season, Lancashire looked like pipping Middlesex, and a letter in The Times, signed by "Fair Play", complained that this was the result of Lancashire playing and beating lesser counties - sides Middlesex did not play. The anonymous writer called on MCC to "exercise its authority and award the title to Middlesex". In the event Middlesex, on the last day before the retirement of their veteran captain, Pelham Warner, won a thrilling victory, and so the letter was forgotten. Only much later was it learned that "Fair Play" was Warner himself.

The points system underwent repeated change. At one stage, there were five for a win and three for a first-innings lead in a draw, which prompted some counties, notably Lancashire, to concentrate on accumulating first-innings points. In 1930 they took the title with ten victories, ahead of 15 by the more adventurous Gloucestershire, who are one of three counties yet to win it. Then there were games where the percentage system made it better for a side to block out for a no-result rather than complete their first innings. Whatever the system, there always seemed to be unforeseen consequences. From 1922 to 1939, the Championship was won every year by a northern county. Their whole focus was on points, unlike most of the southern teams, whose attitude was summed up by the Sussex professional Maurice Tate: If we can win the Championship without losing our characteristic free-and-easy style, we are very happy to do so. But if the effort to attain such distinction means games which are boring to the spectators, irritating to the players and contrary to the true spirit of what we call cricket, then we just as soon remain among the obscure.

Financial problems were never far away. The big games drew great crowds - 46,000 at Old Trafford for the Bank Holiday Monday of the 1926 Roses match - but among the smaller counties times were hard. Glamorgan came close to bankruptcy, while Worcestershire, having not entered a team in 1919, got through the 1920s only by drawing on a large cast of amateurs: a vicar in the Cotswolds played his first Championship match at the age of 57; a prep school headmaster, unable to make a game, sent along one of his staff. Leicestershire discussed amalgamation with Lincolnshire, and in 1937 an MCC commission recommended reducing the Championship to 15 teams. They reckoned only Kent, Middlesex and Yorkshire had sufficient funds to avoid resorting to appeals or borrowing.

The crowds flocked back to cricket after the Second World War, and "Ground Full" signs were commonplace on Saturdays all over the country. This lasted into the early 1950s, a decade in which England went eight years without losing a Test series. The Championship became more centrally organised, with the counties all playing 28 games, including at least one against each of the others. But the crowds gradually thinned out, and by the 1960s the county game was in the greatest crisis it had known. Changes came thick and fast: the abolition of the now phoney amateur status, the start of Sunday cricket, the introduction of three one-day tournaments, the special registration of overseas players, the pursuit of commercial sponsorship and a constant tinkering with the rules. Such was the flux of new ideas that a major committee of enquiry, set up in 1965, floated the option of a competition comprising 16 three-day and 16 one-day games.

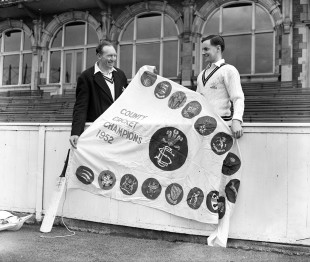

The rise of one-day cricket saw a reduction in the Championship programme from 28 matches in 1968 to 20 in 1972, and there was a great levelling-out of the counties. In the nine years from 1968 the Championship was won by nine different sides, including Leicestershire for the first time. A go-ahead club on the commercial front, their first-choice XI broke new ground by winning the title without a county-born player among them. It was as The Times of 1906 had predicted, especially since Rutland had become part of Leicestershire. For many years there was no prize for the winners. A pennant was created in 1952, then in 1973 the Lord's Taverners donated a trophy which their patron, Prince Philip, presented at Buckingham Palace.

That year, for the first time, there was a financial prize too, of £3,000. In 1977 Cadbury Schweppes became the competition's first sponsors, opting to support the Championship rather than home Tests. Their negotiator, Vernon East, figured that England's matches were "the holy of the holies" and that Schweppes Tests would never be accepted. "I got it 100% wrong," he admits now. From 1978, Cornhill did spectacularly well from the Tests, while some newspapers declined to add Schweppes's name to the competition.

By the mid-1980s the sense of crisis was back, this time provoked by the poor performance of the Test team. Was county cricket to blame? There was a switch to four-day games, followed - in another period of soul-searching - by the introduction of two divisions in 2000, an idea promoted by Grace a hundred years earlier. Within each division, for the first time since 1894, all nine counties played each other home and away; Durham had joinred in 1992.

The counties opted for three-up, three-down to ensure they all had a turn in Division One, but in 2006 it became two-up, two-down, and the gulf between strong and weak widened. With modern employment laws shredding the last vestiges of Lord Harris's eligibility regulations, life is even harder for the poorer counties than between the wars. Like the unwritten British constitution, the County Championship has adapted and evolved. It has never been wholly satisfactory, yet is still the centrepiece of the English domestic game, the competition the players most want to win.

It is 125 years since Grace faced the first ball of the first game at Bristol. Will the Championship reach its 150th anniversary in 2040? If it does, one thing is certain: there will be voices calling for radical change. It is a Victorian creation, starting life in the year newspapers first carried photographs, and it is still with us in the internet age. If nothing else, we should cherish its history and celebrate its resilience.