Engraved in the memory

Rupert Bates

|

|||

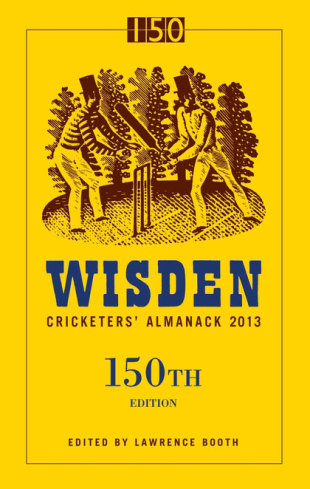

They were never honoured as Cricketers of the Year. But a batsman and a wicketkeeper - both nameless, both virtually faceless - have adorned Wisden now for 76 springs. The wood engraving of the Victorian duo in top hats is one of the sport's most charming and recognisable images. And yet cricket knows little of its creator.

Also celebrated for his watercolours, book illustrations, ceramics and lithography, Eric Ravilious was commissioned to produce the engraving by Robert Harling, the typographer asked to redesign the 1938 Wisden. Harling knew Ravilious had a "special enthusiasm for the game" - though no doubt his deep Wealdean Englishness and sense of tradition helped too - and wrote: "His engraving of mid-19th century batsman and wicketkeeper remains an ideal graphic introduction to one of England's most durable publications."

The engraving briefly lost its cover-star status in 2003, when a photograph of Michael Vaughan relegated it to the spine of the book's jacket, incurring the displeasure of some traditionalists. It was immediately restored to the cover in 2004, while staying on the spine as well. And so, for ten editions now, including this one, Ravilious's creation has been more visible than ever.

Educated at Eastbourne School of Art, he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art. But Ravilious died in 1942 aged 39 when, as an official war artist and honorary captain in the Royal Marines, his plane was lost on a search-and-rescue mission off Iceland. And while it was clear he was never going to decorate Wisden through his on-field achievements, he did leave his indelible mark. In the words of cricket bookseller John McKenzie, the engraving "remains the face of Wisden".

A preparatory sketch from a Ravilious scrapbook has another cricketer in the frame, dressed in top hat, waistcoat and bow tie, with a marquee in the background. Although he wrote many letters to family and friends, he appears never to have explained the inspiration behind the engraving. One theory is that he gained it from a pub sign in Sussex, the county in which he spent most of his life and which provided the backdrop to some of his greatest work, including watercolour landscapes of his beloved South Downs. The Cricketers Arms in Berwick, near Firle - a village where he spent much time - has a top- hatted Victorian batsman on its sign. And the one at the Bat and Ball Inn in Hambledon, admittedly some 60 miles away in Hampshire, also depicts a batsman and wicketkeeper.

But Anne Ullmann, Ravilious's daughter (he also had two sons), insists: "My father soaked up ideas for work wherever he went, but never copied - and I don't believe for one minute that the design was a copy. He may have seen an inn sign with cricketers or, as the sketch suggests, he may have watched a match played in mid-19th century costume. Or he may just have been playing around with ideas for the engraving. But what remains is one hell of a cracking design, and I pray it may represent Wisden for many years to come."

Whatever the origin, we do know for certain that Ravilious played cricket, if at a lowly level. In 1935, he wrote of turning out for the Double Crown Club, a dining club for printers and book designers, against the village team at Castle Hedingham in Essex, where he lived for a while. He said the game went on "a bit too long for my liking and I began to get a little absent-minded in the deep field after tea". He made one not out in defeat, and bowled a few overs. "It all felt like being back at school, especially the trestle tea with slabs of bread and butter, and that wicked-looking cheap cake." He went on to record the comment of the Double Crown captain Francis Meynell that his bowling was "of erratic length, but promising, and that I should have been put on before. Think of the honour and glory there."

In another game at Castle Hedingham, with his wife Tirzah (a talented artist herself) "in charge of the strawberries and cream", Ravilious talked of hitting three sixes. "It is, you might say, one of the pleasures of life, hitting a six."

A shy man, but amusing and invariably cheerful, Ravilious enjoyed the Bohemian company of his artistic friends, who talked of his "Pan-like charm" and the sense that he was always "slightly somewhere else" - no doubt sketching in his head at fine leg, whistling "Better than a Nightingale" below his boater, oblivious to the ball heading his way. Yet it seems no other cricket theme danced on his easel or wood block.

Instead, there is a rich and varied output of beautifully observed landscapes, street scenes, ceramic designs for Wedgwood - including a mug to commemorate the coronation of King George VI - and, in his last years, images of war. The Daily Telegraph called his death "the greatest artistic loss Britain suffered in the Second World War". And in 2011, the art critic of The Observer, Laura Cumming, called him "the lost genius of British art".

Ravilious saw only five of the Almanacks to carry his engraving. Yet his work - in many ways a distillation of Englishness - lives on.

Rupert Bates, a sports and property writer, is Eric Ravilious's great-nephew