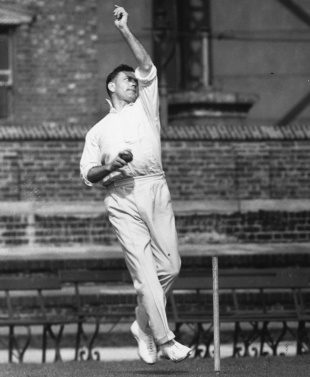

Alec Bedser

|

|||

|

Related Links

Yearly summary : 2011

Essays : A nod of satisfaction Cricketers of the year : Chris Read Cricketers of the year : Eoin Morgan Cricketers of the year : Jonathan Trott Essays : Notes by the Editor Cricketers of the year : Tamim Iqbal Essays : Vintage wizardry Players/Officials:

Alec Bedser

Other links:

Buy the 2011 Wisden Almanack

|

|||

BEDSER, Sir ALEC VICTOR, CBE, died on April 4, 2010, aged 91. In his playing days, Alec Bedser was the epitome of the English seam bowler, the role that represents the nation's often underestimated cricketing virtues more than anything else. In the half-century of retirement that followed - almost all of it devoted to the game he loved - he became something more: the epitome of the spirit of English cricket itself, its values, its history and its perpetual sense of decay.

Hitler's war meant that Bedser did not make his Test debut until he was nearly 28. But he made up for lost time, taking 11 wickets in each of England's first two Tests after the war. For the next decade, he was the engine-room of the team: unflagging in the defeats that came all too often in the 1940s, before emerging triumphant at Melbourne in 1950-51 when England beat Australia for the first time in 15 post-war Tests. And he remained a crucial figure in the Surrey team throughout their triumphant sequence of seven Championships in the 1950s. Later, he spent an unprecedented 24 seasons as an England selector, 13 of them as chairman.

His celebrity went far beyond cricket, because he was not just Alec but one of a pair. His identical twin Eric, not quite an England player himself, was a Surrey stalwart and, by default, a national figure too. In the 1950s, just about everyone in Britain could identify "Alec and Eric" without benefit of their surnames; everyone in cricket had a story about the mystical connections and coincidences that seemed to attend them. Both were bachelors, though the word does their situation no justice: they were virtually inseparable until Eric died in 2006, a relationship that would be hard for even the most devoted spouse to imagine. Modern doctors now urge mothers to let monozygotic twins (the preferred term) develop their own separate personalities. Alec and Eric - peas in a pod from birth to old age - knew no other way and wanted nothing else: they had each other. (For more on this aspect of Alec's life, see Eric's obituary in Wisden 2007, page 1541). They also had cricket.

The boys grew up in difficult circumstances near Woking: their father, a fine non-league footballer, was a £4-a-week bricklayer who - in the phrase later made famous by the politician Norman Tebbit - really did have to get on his bike looking for work. Alec was a Test cricketer before the family had a bathroom. After leaving school, both got jobs as clerks in the same solicitors' office. But in 1938 they tossed aside the security for a place on the Oval groundstaff. Alec was the leading Second Eleven bowler in both 1938 and 1939, when he played, without taking a wicket, in the first-class fixtures against the two universities. He might have become a first-team regular in 1940; instead the twins found themselves under bombardment at Merville and being evacuated from Dunkirk.

Already they had enough celebrity to ease the passage: during the retreat the unmistakable pair were spotted by a van driver who happened to be a Surrey member, and given a lift to the French coast. And they managed to keep together - Alec forewent promotion so he could stay with Eric. Yet their war was not a soft one, and they both got jaundice during the invasion of Italy. When he was in England, however, Alec began to be a favourite choice for wartime matches, and was selected for a powerful England XI against a West Indies XI in front of a huge crowd at Lord's in 1943. He took six for 27, including a hat-trick. So he was not a wholly unknown quantity when cricket resumed. Just in case, though, he wasted no time: in Surrey's first post-war match he took six for 14 at Lord's, bowling out a formidable MCC team for 78. Through the sodden early summer of 1946, he kept taking wickets, even bowling 37 overs (and dismissing Hutton and Hammond) in the Test trial while suffering from a pulled thigh muscle which he had bound up with Elastoplast.

Barely a week later, he took the train, tube and bus to Lord's to make his Test debut. It is true that there was not much competition: his first two England opening partners were Bill Bowes and Bill Voce, both nearly 38. But before the day was done he had bowled India out for 200, taking seven for 49. "Through half-closed eyes it might have been a Maurice Tate out there, hurling them down," wrote Harold Dale in the Daily Express. For once Wisden was more fulsome than the press: "Probably the finest performance ever recorded by a bowler in his first Test," was Hubert Preston's verdict.

When he followed with seven for 52 at Old Trafford, Alec's course was set. It was already clear that in English conditions he was a superb bowler, able to generate exceptional lateral movement off damp uncovered pitches. But the other half of him was to be revealed a few months later in Australia: he was a lionheart. Leading a hopelessly overmatched England attack, he bowled 246.3 eight-ball overs in the Ashes alone without a hint of injury. The Australian spearheads, Lindwall and Miller, bowled less between them. Bedser did get ill in ferocious heat in both Brisbane and Adelaide, where he went to the dressing-room to be sick and walked straight back out again. But that was also the Test when he produced his master-ball: the fast, dipping leg-break that bowled Don Bradman for nought in the final over of the second day.

That ball cemented a lasting friendship with Bradman, and a love of Australia. And his equilibrium on tour was undoubtedly helped by the presence of Eric, shipped out to keep him company through sponsorship from the pools magnate Alfie Cope. The stamina that kept Alec going in Australia would be needed at home in the summers ahead, both for England and Surrey. Year after year, he would bowl more than 1,000 overs (1,253 in 1953, when he was 35) and pass 100 wickets. There was little support, even at Surrey, in the early days.

After two Tests in 1947, England decided they were in danger of running him into the ground and rested him until the following year's Ashes. Again he bowled and bowled, dismissing Bradman four times in the first two Tests (and making 79 as nightwatchman at Headingley). But this was a near-impossible series for England, and Bedser was fighting an uphill battle until the last Test of the 1950-51 series. He took ten for 105 at Melbourne, was hailed as "the best bowler in the world" by the Express, given a civic reception in Woking and had his waxwork placed in Madame Tussauds. The Australian writer Ray Robinson said it should be in the Chamber of Horrors.

By now all the elements of Bedser's bowling were in place. Essentially his method was based on inswing, bowled into a consistent area back of a length and assisted by an absence of restriction on the number of fielders backward of square on the leg side. On wet wickets he could become unplayable. He could also bowl outswing, never stopped thinking and never stopped trying, which was possible well into cricketing old age thanks to his economy of action. He had height, strength, huge hands and ferociously strong wrists. There was also what was most often called his leg-cutter, though those who faced it insist this was an inadequate description. "It was swerve, not swing," says Jack Bannister, who as a tailender came out to face him on a wet wicket for MCC against the Champions in 1955. "I got one that was coming in towards leg stump. The ball ended up going past my right ear and a clod of earth past my left. He was bowling probably around 78, 79 miles an hour. I don't believe anyone has ever moved the ball that much at that pace."

By then Bedser was the linchpin of a Surrey team that were turning into champions in perpetuity, and for England he had partners of the calibre of Bailey, Statham and Trueman. At Trent Bridge in 1953 - a potential thriller wrecked by rain - Bedser had match figures of 14 for 99, and took a record 39 wickets as England recovered the Ashes at last. But soon the young men would eclipse him. On the boat out to Australia in 1954-55 he had shingles, which went undiagnosed. He still bowled 296 balls in an innings in the Brisbane Test and had already changed for the Sydney Test when he saw the team-sheet posted on the door. The captain, Len Hutton, had failed to tell him he had been dropped in favour of Frank Tyson. Bedser played only once more for England, at Old Trafford the following summer: in 51 Tests he had taken a then-world record 236 wickets.

He played on for Surrey until 1960, and took another five-for in his final match, against Glamorgan. By then he was 42, yet he was to remain at the heart of the game. In 1962-63 he went to Australia as assistant manager to the Duke of Norfolk, in charge of both the cricket and the money - he was canny about both. By then he was already an England selector, and was to prove even more undroppable than he had been as a player. He was a conscientious traveller, a shrewd observer and a collegiate chairman, staunchly defending even those selections he had opposed in private (such as the recall of the aged Brian Close in 1976). But his greatest plus, as far as Lord's was concerned, was that he came cheap. As a successful but not overworked businessman (he and Eric owned an office equipment business) with frugal tastes and no family to support, he was happy to devote his summers to the job without pay.

But as the years went by, he had less and less empathy for the younger generation in general, and grew increasingly dyspeptic about England players in particular. Habitually, he would measure them against his benchmark of professionalism - Eric, as his own alter ego - and find them wanting. His fellow-selector Doug Insole once translated Bedserese at a pre-Test dinner: "If he says you're not bad, you're one of the best three in the world." And thus, in time, Alec's greatest virtues, his standards and cricketing integrity, became millstones: his fatalism turned into defeatism and seemed to enter the team's soul. He was always affable, and there was always a certain bleak, even surreal, humour in his grumbling. When he complained about Chris Old carrying his child's teddy bear into the team hotel in Australia, one suspects he was half-teasing himself, just as he had been when he lost a game of deck quoits to John Woodcock on the voyage to Australia in 1954. "You and your effing Oxford University!" he groaned.

When Alec was finally elbowed aside as a selector, he and Eric continued to enjoy the cricketing social scene, their golf and their grumbles. Their friend John Major engineered Alec's knighthood as prime minister in 1997. Their 80th birthday in 1998 was celebrated with a huge dinner at a London hotel, and they kept in fine fettle until Eric's death in 2006. Conventional wisdom had been that, whichever died first, the other would quickly pine away. But perhaps, in his deepest subconscious, Alec felt a sense of release, and for a while he seemed to enjoy a new lease of life without always having to ensure that his less famous brother was included. In 2007, Wisden made a unique presentation to him to mark the 60th anniversary of his selection as a Cricketer of the Year. Alec wept, and soon the whole room joined in. Two years later, his health began to decline but, even in 2009, watching Australia v Pakistan on TV, he was explaining how he would have got Ricky Ponting out.

Buy the 2011 Wisden Cricketers' Almanack