The Stanford Super Series 2008-09

Scyld Berry

|

|||

|

Related Links

Andrew Miller : Money or pride?

News : Windies board faces up to bleak future Tony Cozier : Will the Stanford success bring lasting change? News : Plenty of reasons to smile Feature : We're here to bury Stanford Vaneisa Baksh : What's the shouting about? Fazeer Mohammed : Let's cut out the hypocrisy What They Said About : Girl trouble Players/Officials:

Giles Clarke

| David Collier

| Chris Gayle

| Kevin Pietersen

| Viv Richards

| Allen Stanford

Series/Tournaments:

Stanford 20/20 for 20

| Stanford Super Series

|

|||

In the middle of February 2009, while England were playing the second of their two Test matches in Antigua, Sir Allen Stanford was charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission of the United States with an alleged $9.2 billion investment fraud. The ECB immediately suspended negotiations with Stanford but, by then, they had suffered enormous embarrassment from their close links to the Texan who claimed to be a billionaire. "We are alleging a fraud of shocking magnitude that has spread its tentacles throughout the world," said Rose Romero, director of the SEC office in Texas - and the most surprising, if not shocking, of all the many victims was English cricket.

Much wisdom was expressed after Stanford was charged; and the images of the ECB's top brass virtually throwing themselves at Stanford's feet when he landed at Lord's in a helicopter will be indelible. But the essential fact was that the ECB, during the summer of 2008, did not have much alternative to getting into bed with him.

Giles Clarke, as the ECB chairman, and David Collier, the chief executive, listed several cogent arguments at the time for public consumption. One was that it was better to have Stanford operating inside the tent than outside, like another Kerry Packer. A second was the reality of geopolitics. England had to cosy up with West Indies to ensure their vote at ICC meetings, as the Asian countries would have almost everything their own way if only Australia, England and New Zealand opposed them. Further arguments were also advanced: that West Indies cricket needed English involvement in order to revive, and that tournaments like the Stanford 20/20 for 20 ($20m) would open up the lucrative television market in the USA, an important step in the sport's globalisation.

The most compelling argument, however, for the ECB to accept Stanford's proposals for an annual winner-takes-all tournament in Antigua - along with a four-nation Twenty20 at Lord's - was that their arms were being twisted by some of England's leading players. Kevin Pietersen, at least before he was appointed England's captain in August, was loud in his determination to become a million-dollar cricketer in the IPL, and Andrew Flintoff made similar noises. Their central contracts expired in October - and they could have gone anywhere. In April, a Professional Cricketers' Association survey had announced: "35% of England players said they would consider retiring from international cricket prematurely to play IPL"

|

|||

The threat, therefore, of England's leading cricketers refusing to sign their central contracts and preferring to play in India, instead of in the two Tests against West Indies in early to mid-May, was real and substantial. The rules said the England players would have to obtain No Objection Certificates from their counties and the ECB, but in the feverish climate it was distinctly possible some might retire from national duty and throw in their lot with the IPL, daring England not to pick them for the Ashes. Cricketers were now freer agents than they had ever been before. The ECB had to find them some major dollars, and quickly; and Stanford, for all the doubts about him, was the one available option.

The ECB, mainly Collier who had worked in the United States, made some checks as to whether Stanford could pay; and it appeared as though he could, as this was the Indian summer of the world economy, before the recession bit so suddenly and deeply. Where his money came from was a separate matter: Stanford had some history of controversy in his business dealings, but there again, the ECB argued, so had many other rich businessmen and sponsors of sport. Before the big game on November 1, many expressed concerns about the details of the hasty arrangements, especially the use of the England name; and Collier arrived in Antigua only during the week of the Super Series tournament to try to sort them out. There was, nevertheless, a prevailing belief that the most lucrative ever cricket match should be played, if only as a one-off; and that the Lord's quadrangular (for England, the Stanford Superstars, New Zealand and Sri Lanka) should go ahead. It was also mooted that the Superstars would be one of two overseas teams in the English Premier League of 2010.

It was not long, however, before the misgivings grew. Nature was first to oppose Stanford: instead of the fast, true pitches which 20-over cricket demanded in order to appeal to worldwide audiences, his private ground beside Antigua's airport had slow and uneven wickets which discouraged big hitting. In the first Stanford domestic tournament the average total of the side batting first had been only 136, and in the second 134.

|

|||

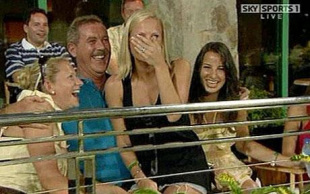

A public-relations disaster followed during the second warm-up game. Stanford, as he owned the place, liked to mingle with anybody he fancied, with a cameraman in tow. So he went into the England players' dressingroom, oblivious to the tradition that it is sacrosanct - while the England players were oblivious to the tradition of American sport that owners can go anywhere. Then Stanford went and talked to some women in a stand, and sat one of them on his knee: it was Matt Prior's wife, Emily, and she was pregnant. Stanford had to ring the England team hotel next day and apologise to Pietersen and Prior. The British press had a field day; the ECB, rapidly getting cold feet, suggested the Stanford tournament might be a oneoff, not the first of five annual matches as originally announced.

The English players became ever more ambivalent. Their culture told them it was distasteful to play solely for money. The fixture was between the Stanford Superstars and England: an authorised but unofficial match, in a distinction specially created for the encounter. It would not count in the official records; a playing regulation allowed the bats to be black; national pride was not at stake. Or was it? The England players were confused and diffident about being seen to try too hard to win a million dollars each. They had also spent a lot of time discussing how the $20m should be divided up, more than in practising their 20-over skills. Eventually, following discussions between the PCA and ECB, it was decided that one million dollars would go to each player; another million would be divided between the four other players in the squad; and another million would be divided among the coaching and management staff. Whatever the result, the ECB and WICB had agreed to split the remaining $7m between them for development.

Middlesex were equally ambivalent and abashed when they, as England's domestic 20-over champions, met Trinidad & Tobago, winners of the second Stanford domestic tournament. Trinidad had unfettered enthusiasm and three spinners on their side, and easily knocked off the runs, even though it was an advantage for Middlesex to bat first on another uneven pitch. The following day Trinidad came within a stroke of beating England, when they needed three off the final ball to win a warm-up match.

All through the week the floodlights had been poor and the catching even worse: at least half of the offered chances went down. But the day before the final the lights had their caps removed. Like a schoolboy's cap, the cover over each light had been designed to cut down the glare for pilots landing on the runway a few hundred yards from the ground. On the big night the lights, at last, were fine; only one catch was missed; and although the firework display after the game had to be delayed for ten minutes while a plane landed, it was worth the wait. Whatever Stanford did, it was not by halves.

Without question, the winner-takes-all match did some good to West Indian cricket. When Stanford took the microphone after the prize-giving ceremony, his first words were: "Let me say this - cricket in the Caribbean is back!" And if there was some characteristic hyperbole, this was undeniably a stage in the regeneration process. For, at last, most of the best West Indian cricketers were financially rewarded. They had been poorly paid - given the cost of living in the Caribbean, perhaps more so than the players of any Test-playing country, without an industrial or commercial sector to provide sponsorship. But for six weeks' hard training in a camp in Antigua, run by Eldine Baptiste and Roger Harper, they now received a million dollars per player. Aspiration was rewarded, and visibly so. Sir Vivian Richards, chairman of the Stanford selectors, said the team looked "a very professional unit" - and they were fit, strong and excellent fielders, besides being superbly captained by Chris Gayle. Although the Stanford Legends were paid to attend, there was a rapprochement between the past greats and the current generation, a coming together, a mutual recognition; whereas the West Indian cricketers of the 1960s to 1980s era had felt let down, even betrayed, by some of their successors.

Pietersen said that, if England were to return for future tournaments, they would have to be far more committed. The West Indians were unabashed. Gayle said it was the happiest moment in his life, and he would spend the money partly on heart operations for his father and brother. (Gayle had missed the Superstars' first practice game, against Trinidad, because of "personal problems" that attracted much speculation.) Unfortunately, it later emerged that a few of the West Indian players had invested some of their money with Stanford.

If there were always reservations about the ways Stanford had made his money, there was no doubt he spent some of it to the benefit of West Indian cricket, as well as generating lots of publicity for his business. But the real justification for the tournament could only be decided in the future: if the $3.5m destined for each board was actually spent on development - on grassroots cricket such as the Chance to Shine programme - instead of disappearing into the general coffers.

The West Indian board never received their money. Stanford had fallen out with them after they sold the title sponsorship rights to the Stanford Super Series to Cable & Wireless. Digicel took the case to the High Court in London and successfully argued that they already held the rights because the Stanford Superstars were West Indies in all but name.

|

|||

England did receive their $3.5m - but, far from spending it on "development" as most people understood the term, they allocated $2m to the 18 first-class counties to help them in the recession, according to a press conference given by Clarke and Collier on the day of the big game. Thus, very little was going to be done for the greater good: the Stanford Super Series was designed to line the pockets of the few.

As soon as the charges were levelled against Stanford, there were loud calls for the resignation of Clarke and Collier. Essentially, though, it was English cricket which was at fault and, specifically, the ECB and its constitution. The lesson was that a handful of great and good, without any vested interests such as close links to the counties, need to govern with the best interests of the whole sport at heart. Clarke and Collier got into bed with Stanford because the England players and the counties wanted them to; and to preserve their respective jobs they all too willingly complied. The summer of 2008 saw the final surge of unfettered Western capitalism, for now; getting rich quick was all that mattered, and the ECB followed the herd.

The tournament, being authorised but unofficial, also saw an experiment in umpiring. In the Sri Lanka v India Test series a few months before, players had been allowed to refer questionable decisions to the third or television umpire. In Antigua, a consultation process between the three umpires was tried, without any players being involved. In a practice game Rudi Koertzen, the TV umpire, should have intervened after seeing the Trinidad batsman Justin Guillen given out by Asad Rauf: the ball had not hit his bat, only Guillen's arm, before being caught. But the mistake was admitted, and the co-ordination between the three officials improved. On the big night, justice was done, and seen to be done, when Fletcher was given not out after an appeal for caught behind, and when Harmison appealed for a ball pitching just outside leg stump, both referred by Koertzen to the TV umpire Steve Davis. Consultation seemed the way to go, at least for limited-overs cricket, but the ICC were already committed to further trialling of the referral system.

Regrettable as the whole Stanford episode was, it would be a pity if this useful experiment and other positives from the Super Series were to be forgotten.

Match reports for

Stanford Superstars v England at Coolidge, Nov 1, 2008

Report |

Scorecard

Match reports for

Stanford Superstars v Trinidad & Tobago at Coolidge, Oct 25, 2008

Report |

Scorecard

England v Middlesex at Coolidge, Oct 26, 2008

Report |

Scorecard

Middlesex v Trinidad & Tobago at Coolidge, Oct 27, 2008

Report |

Scorecard

England v Trinidad & Tobago at Coolidge, Oct 28, 2008

Report |

Scorecard

Stanford Superstars v Middlesex at Coolidge, Oct 30, 2008

Report |

Scorecard