The little master

Tony Lewis

|

|

|

It is tempting to write an appreciation of Sunil Gavaskar in extravagant language so that it matches the pinnacle to which he took his batsmanship. Reflect on the career of a man who played in more Test matches, scored more runs and hit more hundreds in Test cricket than any other and you think in heroic terms. Imagine his beginning in Bombay and the romance flows. It is 1951, he is two years old, up on the balcony of his parents' flat in the Chikalwadi district, defending a door with a toy bat as a tennis ball, gently propelled by Meena, his mother, bounces towards him. Link that to the fairytale last appearance at Lord's, where he had never scored a century. In MCC's 200th-birthday match he constructed an innings of 188, all patience and style, which demonstrated to many who had not seen him in his pomp that here was art fined down, skills chiseled to something simple yet beautiful and lasting.

However, ornate language does no suit Sunil Gavaskar, even though Sir Donald Bradman rightly described him as an ornament to cricket. Gavaskar is a man who does not live in luxury though he could afford to. His middle-class English accent is cultured and he is articulate, but he is frugal with his words, often preferring silence. His eyes can twinkle and he has a relish of fun; he delivers the one-line joke like a knockout punch and is mischievous in mimicry. Yet Sunil Gavaskar's eyes can also turn to fire, his face burn with anger, and deep in the small frame you can hear the fighting spirit of the old Marathas thunder.

It is impossible to think of Sunil without his wife, Marshniel, known to the cricket world and her friends as Pammi. Think of solid partnerships -- Hutton and Washbrook, McGlew and Waite, Greenidge and Haynes, Mohsin and Mudassar, Marsh and Boon, Contractor and Roy, and you would have to say Gavaskar and Pammi. This is not because Sunil's opening partners have changed so often, but because with Pammi, whom he married in 1974, he merges; he gossips and relaxes. Also he has someone to share his drive. Once the objective was a massive collection of runs; now business ambition, which has always floated just under the surface, gives them the purpose they need in everyday life.

I first saw Sunil Gavaskar bat when I led MCC in India in 1972-73. We had been warned to expect something special by his incredible performances in his first Test series in the West Indies in 1970-71. He scored 774 runs in eight innings at an average of 154.80, including 124 and 220 in the Fifth Test at Port-of-Spin. He had not been as successful in England later in 1971 but now, about to play his Test in India, he had the subcontinent longing to greet a little master.

|

|

On the first day's cricket of that tour, against a President's XI, we bowled to him until the final session, when he was run out for 86. The Fateh Maidan in Hyderabad was hot and noisy and none too comfortable; the dragonflies buzzed low and we gulped down the salt drinks on the hour. The large crowd's roar never subsided but occasionally welled up to the accompaniment of firecrackers. Gavaskar reminded me of Geoff Boycott -- detached, insular, totally within himself and not given to banter with players, umpires or even his partner. He looked neat, 5ft 4¾in tall, and strong in the legs and forearms. His kit was clean, his appearance smart. Another Boycottism, I thought; preparation perfect for the pursuit of runs. And more Boycott in the sideways stance, the small first movement of the back foot, the sharp downward angling of the bat in the forward defensive stroke. He scored slowly, but it was important for him and for India that he took as much practice as possible against the English bowlers before the Test series began. His concentration was absolute.

Of course, Bombay already knew about Sunil Gavaskar's single-mindedness. His father, Manohar Gavaskar, had been a fine batsman and wicket-keeper in club cricket, and his maternal uncle, Madhav Mantri, had played four times for India. The former fired his enthusiasm, the second shaped his thinking. By the age of twenty he had put away all childish strokeplay and made 327 for Bombay University in a trophy match. In our particular Test series runs eluded him, but that just meant that he had a more realistic base from which to develop. Soon I was watching him from the commentary boxes of the world and my pleasure in seeing him bat has not wavered over fifteen years.

Quite unforgettable was his 101 out of 246 against England at Old Trafford in 1974. Cold north-west winds drove in squalls, bringing only the seventh day of rain in Manchester since mid-February. The pitch was firm and bouncy, Willis, Old and Hendrick were hostile, whacking in the short balls. Underwood and Greig were the slower bowlers and they gave nothing away. Gavaskar first demonstrated how brave he was. He kept his eye on the ball and swayed either side of the high bounce, but when the ball was pitched up he was immediately forward to drive it straight. This is where Gavaskar was a better player than Boycott overall. Boycott lost his strokes, or maybe through parsimony he cut them out; Gavaskar reduced risk, too, but never lost the spring off the back foot which sent him firmly into the drive.

Quite recently, in a BBC television interview, I asked him about that first move back and across. He replied, "I just worked out the best method for my height. If I had gone looking to play forward, I would have been hit on the head all of the time. Playing back gave me options to sway, duck and drop the wrists or hook if I was in position to do so." That Saturday at Manchester he certainly hooked many times -- a shot he usually ignores -- and with his brother-in-law, Viswanath, he played handsome strokes with the debris of an innings around him.

Sunil Gavaskar has never been a dedicated net-player, and he never appears to thrive on too heavy a programme of cricket. It is interesting to note that he scored 39 per cent of his first-class runs in Test cricket, whereas Boycott's percentage was 17. He has an independent mind and sees a much wider world than cricket available to him. For example, when he joined Somerset in 1980 he was unhappy. At close of play the Somerset cricketers would be off to the beer tent where they would chat about cricket. Sunil preferred to retreat from cricket to different conversations and take a quiet glass of wine with his dinner.

|

|

|

Indian cricket has now lost a great player. He became a better one-day cricketer as he came to enjoy the game more in his later days. He had proved everything and he delighted in leading India to victory in what was called the World Championship of Cricket in Australia in 1984-85. His perverse moments were now behind him: as when he walked off the field and took Chetan Chauhan with him as a demonstration against Australian umpiring; as when he called the Indian selectors "court jesters"; as when he refused ever to play again in Calcutta after he had delayed a declaration against David Gower's team and almost caused a riot.

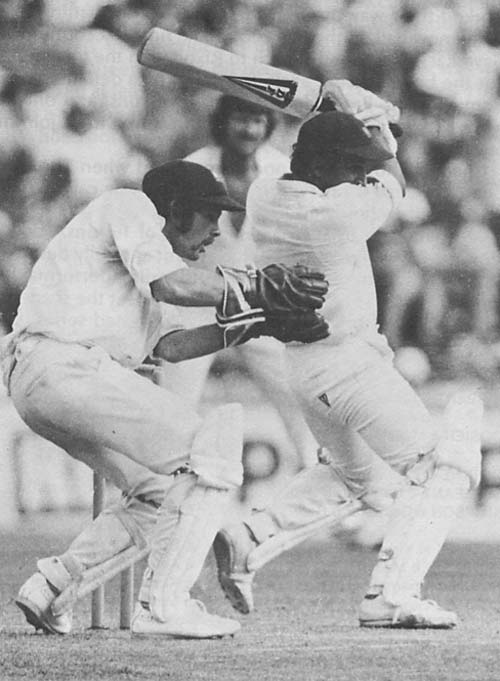

Only the good thoughts will remain and they are precious. Sunil Gavaskar will be remembered for his rolling walk to the crease, his forearm padded against the fast bowlers. His deflections to fine leg will remain clearly etched, as will his firm pushes in a wide arc on the leg side, his drives, of course, and his lethal cut to square third man. But I will recall most the best player of spin bowling I have ever seen, always balanced, forever with time whether playing right out to the pitch of the ball or back to watch and wait. If he fell victim to Derek Underwood more often than he would have wished, it only praises Underwood's deception in the air which was often underrated.

As 1989 progresses, no doubt Sunil sits in his high-backed office chair in his beloved Bombay; around his neck will be hanging the locket on the gold chain given him by the religious man, Satya Sai Baba. I guess his patron and mentor, Virenchi Sagar of Nirlon, who gave the young Gavaskar security and a business future, will not be too far away. Sunil and I shared a car in Sharjah recently and he talked urgently about his ambitions in sports publishing, video and television. He had that same resolute look in his eye; the second game has started. You would not wish to be Mr Gavaskar's opponent in any field.