Champagne moments

John Crace

A tired Fred Trueman leans on Colin Cowdrey after becoming the first bowler to get 300 Test wickets © Getty Images

It was the image of the summer: Stuart Broad wide-eyed and open-mouthed as Ben Stokes somehow caught Adam Voges at fifth slip on the first morning at Trent Bridge. And it was a celebration like no other. When a fast bowler takes a wicket these days, the default response is to run joyously into the arms of the keeper and slips, with the option of firing off a few sledges at the departing batsman. But, for a split second, Broad seemed to stop in his tracks, the amazement undisguised; along with everyone else, he had assumed the ball was heading to third man. Professional cricketers like to make out they've seen it all before, that genius is to be taken for granted. But the mask slipped - and Broad became almost childlike.

Most cricket celebrations are lost: there is no visual record of how W. G. Grace acknowledged a century, and such first-hand written accounts as do exist are refracted by the stiltedness of the time. The emphasis is on the effect WG has on the crowd (match reports contain plenty of "cheering"), rather than the man himself.

It makes the odd exception all the more delightful. So when WG scored his 100th hundred in May 1895, his brother EM arrived in the middle with a bottle of champagne. WG was evidently unsated: two hours later, EM returned with another bottle to celebrate the double-hundred. Fortunately for Bristol's champagne supplies, he eventually fell for 288. But, at a time when sportswriters could still describe the action and the atmosphere safe in the knowledge that the story would not be common currency by the time their reports appeared, the very modern impulse to get inside players' minds was all but absent.

One giant leap: David Warner routinely celebrates his batting milestones with a dramatic high jump © Getty Images

With decorum the cricketers' watchword, it was the crowds who continued to express the emotion of the moment. The Bodyline tour of 1932-33 was one of the first for which newsreel footage exists. Watch the highlights, however, and you might struggle to realise this was one of the most ill-tempered series in history. Nor would you have guessed that England's 4-1 victory was the result of Douglas Jardine's meticulous planning. Australian wickets are greeted with nothing more than a gentle stroll towards the bowler, and the occasional gentlemanly shake of the hand. The only hint of menace comes from beyond the boundary.

A revealing loss of self-restraint comes at Lord's in 1948, when Australia won by 409 runs. Each of England's second-innings wickets is greeted by stony faces. But, when the last falls, the veneer cracks. It emerges that the Australians haven't spent their time working out how to dismiss England (like so many over the years, the England batsmen have worked that out for themselves). No, they have been ensuring they are handily placed for the memorabilia. When Doug Wright is caught by Ray Lindwall off Ernie Toshack, there is the briefest of pauses to mark the fall of an old enemy - before the Australians make an unholy dash for a souvenir. While four players engage in a scrap for the stumps at one end, a fifth wrestles one out of the umpire's arms at the other.

That followed farcical scenes at Trent Bridge, where Australia's Sid Barnes had nearly reached the pavilion, stump in hand, having made what he thought was the winning run. In fact, the scores were level. When the coup de grâce was applied moments later by his partner, Lindsay Hassett, Wisden recorded that "another scramble for souvenirs took place; and in this Barnes was unlucky". The authorities soon made sure that such indecorous scenes became a thing of the past.

All in a day's work: Jim Laker walks back after taking all ten Australian wickets at Old Trafford, 1956 © PA Photos

Even so, the modern fan might be shocked by the lack of emotion at Old Trafford in 1956, when Jim Laker's tenth wicket of Australia's second innings - and 19th of the match - was greeted with something close to sheepishness. As he explained nearly three decades later in Cricket Contrasts: "There were no leaps in the air, no embraces, no punching the sky, just a dozen polite handshakes as I slung my sweater over one shoulder and jogged quietly up the pavilion steps." That's how men were back then.

On his way home that evening, Laker stopped in a pub in Lichfield, and bought "a couple of very stale cheese sandwiches" and a beer. He sat quietly at the end of the bar, watching highlights of the day's play on a black and white TV, "listening in fascination to the comments of the other customers". No one congratulated him because no one recognised him. Fast-forward nearly 50 years to the Trafalgar Square celebrations for England's 2005 Ashes winners, and there was no such issue.

It's hard to pick a turning point. Some believe it was the final over of the tied Test between Australia and West Indies at Brisbane in 1960-61. When Richie Benaud was eighth out, caught behind off the second ball of the final over, only wicketkeeper Gerry Alexander looked at all pleased. And when, with Wally Grout pushing for a third run that would have brought Australia victory, Conrad Hunte ran him out, the West Indians made little fuss: Wes Hall returned to his mark as if it was another day at the office. It was only when Joey Solomon ran out Ian Meckiff that bedlam ensured.

Shout and let it all out: Dale Steyn threatens to burst a vessel while celebrating a wicket © Getty Images

It was as if cricket needed a cliffhanger to get the blood pumping. When Fred Trueman became the first bowler to 300 Test wickets, at The Oval in 1964, by having Neil Hawke caught at slip by Colin Cowdrey, the fielder appeared as relieved as the bowler. Trueman was nearing the end of his career, wickets were getting harder to come by, and there would have been hell to pay had he dropped it. As it was, Trueman barely broke stride as he shook the outstretched hand of the outgoing batsman. Truly, another era.

By 1967, when I attended my first Test - against Pakistan at The Oval - celebrations were still on the quiet side of muted. My only memory is of training dad's binoculars on Saeed Ahmed, as his middle stump was sent cartwheeling by Geoff Arnold. I seemed to find the event infinitely more thrilling than Arnold did: I celebrated more extravagantly in my own back garden when I yorked my mother. Maybe it was because I watched more sport on TV than the average professional cricketer. I had seen England win the World Cup at Wembley in 1966, when the near- toothless Nobby Stiles danced his jig. I had seen George Best run to the fans, arms aloft, after scoring wondergoals on Match of the Day. This was more my kind of sport, red in tooth and claw. I longed for cricket to catch up.

It took a while. Cricket, more than most games, is defined by its codes and conventions. No one wanted to break ranks and give full expression to their delight. It was as if some of the freer spirits were secretly hoping a colleague would go wild, so they could follow suit.

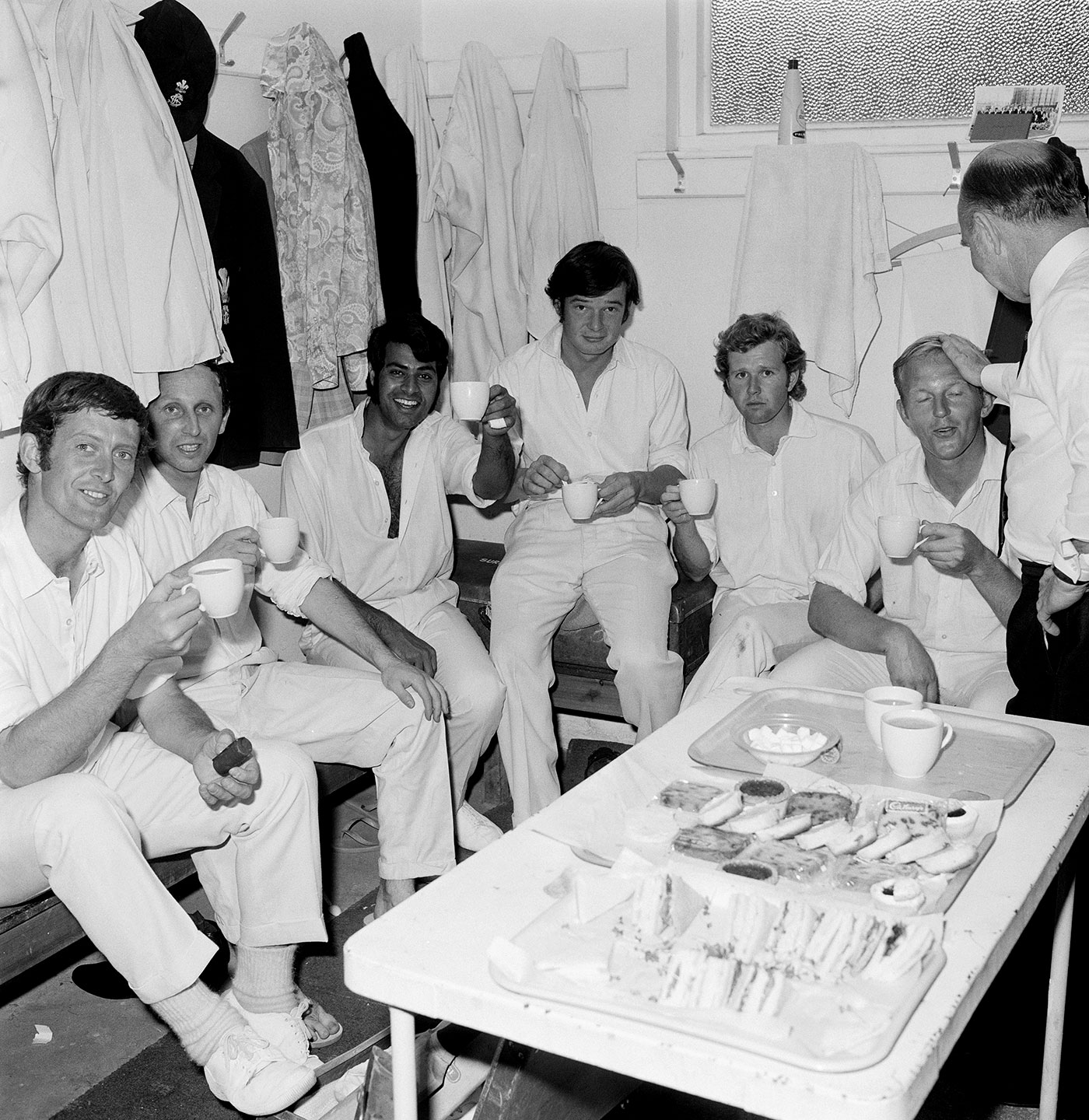

Won the Championship? Let's celebrate with some tea and sarnies © Getty Images

Even some of the greatest mavericks of the 1970s kept a lid on it, including Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson during their demolition of England. Thomson lazily puts one arm - sometimes two - in the air and walks diffidently towards the slips. Only Rod Marsh looks excited, tucking his knees into his ample stomach as he jumps in the air. Too much man-love is too non-cricket, especially in 1970s Australia.

Nor were the great West Indian pacemen much more expressive. Michael Holding would merely turn to check the umpire had given the correct decision before jogging towards his slip fielders. Joel Garner seldom got round to raising an arm. Perhaps wickets came too easily. The cricket may have been terrifying, but the celebrations were low-key. Pundits liked to call it a sign of respect for opponents, but that was a misguided distortion. You can still respect your opponents and embrace the excitement of the moment: there is no contradiction.

If anything, batsmen were even coyer: a landmark would be greeted with a tip of the cap or, in extremis - such as Geoff Boycott scoring his 100th hundred at Leeds in 1977 - with both arms held aloft. The closest to genuine personality had been Derek Randall doing a cartwheel after taking the winning catch in the same game."It is something I had been coaxing him to do at some opportune moment throughout the series," said his captain Mike Brearley."He had been afraid of both the selectors' and the public's opinion but now, at the most opportune time, he had done it." But then over-the-top celebrations can always look premature if you are out shortly afterwards. Far better to keep things understated. And, for years, batsmen had seen themselves as the officer class. It wouldn't do to let oneself go before the bowlers.

Stuart Broad can't contain his amazement after Ben Stokes pulls off a spectacular catch at Trent Bridge, 2015 © Getty Images

Memory is invariably selective and culturally specific: everyone will have their own image of the moment cricket finally gave in to the thrill of the thrill. For me, it was the 1981 Ashes: Bob Willis running round in a - by his standards - delirious little circle after bowling Ray Bright to win at Headingley, and Ian Botham racing down the wicket and pulling out a stump after bowling Terry Alderman to win at Edgbaston. For Indians, the key memory may be when their team beat West Indies to win the 1983 World Cup. Certainly it was in the early 1980s that the dams broke. By now cricket had become a global game, with television highlights available almost anywhere. Celebrations could be seen all over the world as they happened - and copied.

Since then, they've become ever more elaborate. We've had batsmen kissing the turf or the badge on their helmet or the crest on their shirt - although the Australian Doug Bollinger once mistakenly kissed the sponsors' beer logo instead. We've had bowlers submerged in joyous huddles of fist-pumps and high-fives (except South African leg-spinner Imran Tahir, who heads off on a lap of honour). We've had Monty Panesar's ingenuous skips and leaps, and Indian seamer Sreesanth twirling his bat round his head like a cowboy with a lasso after hitting South Africa's Andre Nel for a straight six. And we've even had anti-celebrations, such as Nasser Hussain gesticulating grumpily to the No. 3 on his back in the direction of the Lord's media centre after reaching a one-day century against India in 2002 (England still lost, so perhaps his critics, who said he was batting too high, were right all along). Cricket is the better for all of them.

The only celebration that feels wrong is the one that seems unnatural. Glenn McGrath's attempt to claw back some credit for the bowlers by holding the ball aloft after taking a five-for felt awkwardly self-conscious. Which is why Broad's reaction was so memorable. Where some victory dances look scripted, his was entirely spontaneous and unrepeatable, an act of accidental creativity that defined a series. In the end, though, it's a matter of taste. My own favourite is the sight of the Bermudian Dwayne Leverock catching India's Robin Uthappa during the 2007 World Cup in the West Indies.

Bringing up the rear: these days bum pats are a popular way of expressing appreciation of a fellow player © Ryan Pierse/Getty Images

Leverock was about 20 stone, mostly made up of fat. He was almost certainly fielding at slip only because he would have been a liability anywhere else. Early in the innings, Uthappa got a thick edge, and Leverock dived horizontally to his right to pull off a remarkable airborne catch. He didn't know what to do with himself, running first towards fine leg, then third man, before coming to a halt, presumably exhausted. This was the victory of the common man, for all those of us who are the wrong shape and a bit useless yet still turn out every week for club sides. It was the celebration that fulfilled cricket's ultimate promise, that every dog can have his day.

This article first appeared in the 2016 edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. John Crace is the parliamentary sketchwriter for The Guardian.