Richard Benaud

|

|||

|

Related Links

Players/Officials:

Richie Benaud

Teams:

Australia

|

|||

BENAUD, RICHARD, OBE, died on April 10, aged 84. The career of the man known across the cricketing world simply as "Richie" is almost impossible to sum up succinctly. He was one of the game's finest all-rounders, developed into an outstanding and innovative captain, and then - for 50 of the 70 years in which cricket has been televised - acquired an unrivalled reputation as its leading TV broadcaster. Perhaps Benaud's most significant contribution, however, was his most contentious. In 1977 he broke with the game's establishment and joined Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket as chief commentator and spiritual father. He gave the venture a credibility and respectability that was essential to its triumph, and the transformation that ensued.

At the root of all he did was a sense of determination and integrity that went beyond fierce and bordered on the intimidating. He was successful at almost everything he attempted because he left as little as possible to chance, even when he was betting on horses. It was an attitude he acquired early. Richie's father, Lou, was an accomplished grade leg-spinner - he once took all 20 wickets in a two-innings game - who sacrificed his hopes of a first-class career because he was a schoolteacher in New South Wales, a state in which teachers were expected to go where they were sent.

Despatched in the thick of the Depression to be the sole teacher in Jugiong, 200 miles from Sydney, Lou gave up his cricketing ambitions to support his wife and, at the time, his only child. (Brother John, who also became a Test cricketer, was born when Richie was 13.) Lou cleared a small room to teach Richie how to play properly, defensive shots first. The leg-spin came later. By the time the family returned to the city, it was too late for the father but perfectly timed for the son. At 16 he was playing first-grade for Cumberland; at 18, on New Year's Eve 1948, he made his debut for New South Wales, alongside four of the newly returned Invincibles. In a rain-affected match, he scored two and was not asked to bowl.

Benaud's progress was far from serene. A week later he went to Melbourne for a state Second XI match against Victoria. Sent in as nightwatchman, he progressed to 13 comfortably enough, but next morning misjudged a hook and shattered a bone in his forehead - early confirmation of a penchant for on-field accidents. For nearly a year after that he had to concentrate on his job as a clerk in an accountancy firm, and the next chapter in his autobiography was headed "Promising much but delivering little".

He promised enough, however, and in December 1951 delivered a maiden first-class century, earning him an unexpected debut in the final Test of the 1951-52 series against West Indies, which Australia had already won. His major achievement was to run out Frank Worrell, his future opponent and comrade-in-arms, yet he did not look overawed. In those post-Bradman summers, with Australia now far from invincible, the selectors were searching for agile youth, especially the next season against the fleet-footed South Africans. Benaud can hardly have been worth a place on his figures either as batsman or bowler. But fielding was high on the list of virtues instilled by Lou. And, along with the prodigy Ian Craig, Richie seemed to embody the new spirit the selectors wanted.

He tried their patience, though, as South Africa held the mortified Australians to a 2-2 draw. Benaud appeared in the last four Tests, played a decent yet ultimately futile rearguard at the MCG, and bowled manfully at Adelaide; but he achieved neither a fifty nor a fivefor. He was even less successful in 1953, when England regained the Ashes after 19 years, and was omitted from the Third and Fifth Tests. He continued to get injured in strange ways; the seam was ripping his fingers to shreds; and there was a sense that he concentrated too hard and thought too much.

But he was steadfast around the counties and, at Scarborough in September, got something out of his system, smashing 135 against T. N. Pearce's XI, England players all, including 11 sixes, equalling the world record. Something even more important happened in Scarborough. The previous night, Benaud - who never believed you could learn too much - had dinner with Bill O'Reilly, the sage of leg-spin. "Bill talked, and I listened."

He did more than listen; he made notes, and referred to them again and again, later adapting them to give masterclasses of his own. Back home, in the wholly domestic summer of 1953-54, he was New South Wales's leading batsman - he hit a ferocious 158 against Queensland - and, at 23, was appointed Cumberland's captain. When England successfully defended the Ashes in 1954-55, Benaud was ever-present but again largely irrelevant: after that series, he had played 13 Tests, averaging 14 with the bat and 37 with the ball. However, almost immediately afterwards Australia travelled to the Caribbean, and here he finally began to make an impact: three wickets in four balls at Georgetown, and a 78-minute hundred in the final Test at Kingston. These were soft successes: the not-quite-hat-trick involved tailenders, and his century was the fifth in an innings that reached 758 for eight.

But Australia won the series well against a mighty batting team, and there was no need for scapegoats. And so he came back to England in 1956. It was no kind of summer for Australia - except, as was the 20th-century custom, at Lord's: Benaud took a stunning gully catch to dismiss Colin Cowdrey, and hit a decisive 97, the Australians' highest score of the series (he fell trying to smash Fred Trueman for four). Mostly, though, in journalist Malcolm Knox's words, he was being picked as "an investment that had gone too far to wind back".

On the way home, the team faced four Tests in the subcontinent. Benaud was still working on his bowling, this time shortening his run, which produced a startling seven for 72 in Madras. But he contracted dengue fever, and his fingers were a perpetual bloody, painful mess. The answer to that came a few months later, on a non-Test tour of New Zealand, when he walked into a chemist's shop and met an affable pharmacist called Ivan James. "I think I've tried everything," said Benaud despairingly. James suggested a combination of oily calamine lotion and boracic-acid powder. "The word genius is much overused in our society," Benaud wrote later. "Mr Ivan James turned out to be a genius."

In South Africa in 1957-58 he had a further weapon, a flipper, perfected in the nets at the Wanderers on hot afternoons when his team-mates were having fun. In the opening game against a Northern Rhodesia XI it brought him nine for 16: seven batsmen lbw or bowled playing back to his new trick, deliberately pitched short to barrel through low. He made 122 in the opening Test of the ensuing series; in the middle three, his flipper and Ivan James's magic formula helped him to 23 wickets in five innings. There was no more underachievement, and a year later he was captain. It had, however, been no smooth ascent. Craig, the anointed one, contracted hepatitis; Neil Harvey had antagonised the Australian board - he complained about the pathetic pay (£375 for a full Ashes series plus £50 expenses), moved from Melbourne to Sydney to accept a job, and led an Australian XI to a disastrous pre-series defeat against MCC in which the England captain Peter May scored two lordly centuries. Don Bradman, influential as ever, pushed for Benaud, and prevailed.

England, expecting their fourth successive Ashes win, in 1958-59, were hardly perturbed. The cricket grapevine worked slowly in those days, and they still thought Benaud was the indifferent bowler they had seen in 1956; instead he took 31 wickets. And May certainly never foresaw the flair he would bring to leadership in a series when his own captaincy was "stereotyped", while his opponent was, according to Wisden, "inspiring", "fearless" and a "driving force". Benaud was backed up by total loyalty from Harvey, two big centuries from Colin McDonald, and an attack featuring Ian Meckiff, who - it has to be said - chucked. Australia won 4-0.

|

|||

In 1959-60 Benaud captained the team to Pakistan and India and won both series, taking 47 wickets in eight Tests. His apotheosis came a year later when Worrell, belatedly appointed West Indies captain, arrived in Australia with a side willing and able to play in a manner that moved Test cricket forward from the dull defensiveness of the 1950s. The glorious freak of the tied Test at Brisbane brought forth an enchanting series, the tone set by the two captains. But it seemed characteristically Benaudish that, for all the gambling and attacking, it was Australia who narrowly prevailed. The same would happen again a few months later in England, where another tight series was settled by Benaud in just 20 minutes before tea at Old Trafford. England were 150 for one and coasting towards a target of 256. Benaud tried the then-novel tactic of bowling round the wicket into the footmarks: he took five for 12 in 25 balls, one of the most decisive spells in Test history, and six for 70 in all. It was widely described as a last throw of the dice; as ever with Benaud there was more to it than that. It was a bet on an outsider, but a shrewdly placed bet. He had talked the idea through the previous night with Ray Lindwall, who approved, while warning that it would have to be perfectly executed - which it was. He was one of the Five Cricketers of the Year in Wisden 1962, completing a unique double by also contributing the essay on one of the others, his mate Alan Davidson.

By now Benaud was recognised not just as an outstanding captain, but as a standardbearer for the game: he had come to England promising no dawdling, no ill feeling, no arguments; he had kept his word. With his good looks, his openness and his informality - an extra shirt button usually undone - he seemed to fit with the emerging global cult of youth. But he no longer felt so young himself. He had missed Australia's win at Lord's because his right shoulder was in a terrible state, and the Old Trafford win was made possible only by intensive physio.

But he was not done: he led NSW to their ninth successive Sheffield Shield in 1961-62, and retained the Ashes in 1962-63 after a 1-1 draw with Ted Dexter's team, ensuring he never lost any of his six series as captain; Wisden noted that his leadership did seem a little more cautious. He planned to fade out after the home series against South Africa a year later; in the opening Test at the Gabba he became the first player to reach 2,000 runs and 200 wickets in Tests. The following weekend, playing for Cumberland, he went for a slip catch and broke his poor old spinning finger in three places. Calamine could not save him this time. He missed the Second Test and, though he would return for the last three, ceded the captaincy to Bob Simpson. He retired at Sydney, after his 63rd Test, still only 33. He had, however, been planning for this moment. He was not going to be an accounts clerk.

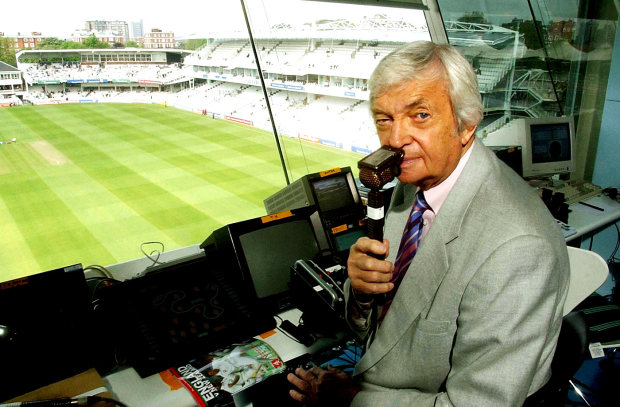

Benaud had long since moved from his first dreary job to the finance department of the Sydney Sun, under a kindly cricket-loving boss. But, in 1956, already in the Australian team yet far from secure, he had asked for a transfer to the editorial department. Sure, said the editor, who offered him a sports column and, if he liked, a ghostwriter to do the actual work. No, said Benaud: he wanted to learn the trade the hard way. The competition between Sydney's evening papers in the 1950s made old-time Chicago look soft, and Benaud asked to be assigned to the police round, the toughest, most competitive area of all. It was not unhelpful being a celebrity, but he did the hard yards. That same year, with TV just starting in Australia, Benaud organised a special three-week BBC training stint in the gap between the team's English and subcontinental tours. He was allowed to shadow the racing commentator Peter O'Sullevan (who died nearly four months after Benaud), and observe his meticulous preparation; and he watched, listened and learned. These experiences also helped develop a sense of the embryonic art of PR that served him well as captain. And, in 1960, he came to Britain again to work for the Sydney Sun, the BBC and the News of the World, beginning a connection with Britain's top-selling newspaper that lasted more than half a century until it predeceased him, in 2011. Three years later, in the brilliant summer when Worrell's team toured England, the BBC invited him to join the TV commentary team, starting the career that would make him more famous than ever. This would also last half a century, and long before the end his commentaries were regarded by the public - even his colleagues - with a quasi-religious reverence ("But Richie said…"). Unlike Bradman, he never became an official administrator, but the power of TV gave him arguably greater influence. It was, for instance, Benaud's verdict of "disgraceful" which ensured that Trevor Chappell's underarm ball in 1980-81 would be a one-off aberration.

He was not an instinctive genius with words, as John Arlott was; people did not habitually switch on because Richie might be commentating. Indeed, a minority found his style rather chilly. The crucial element of Benaud's commentary was absence: the absence of prattle, the absence of errors. Behind this was the meticulousness he learned from his father, O'Reilly and O'Sullevan. He would scan the ground with binoculars while on air, looking for detail on the field and off. And he could rush between stints on the BBC (or, later, Channel 4) and Packer's Channel Nine, switching as required between the understated English style and the more talkative Australian one, always remembering to give the score the right way round: 50 for one for the Poms; one for 50 for the Aussies. The attention to detail never wavered, even when he left the box for the day: he would always, a colleague noted, carry two bags so he could reasonably refuse to sign autographs until he reached his car. Once there, though, he obliged happily. Probably his greatest influence on cricket emerged from a private meeting in 1977, when he met Packer and agreed to lend his name and voice to World Series Cricket.

Characteristically, he said yes before even discussing his fee. He had no loyalty to Australian cricket's existing broadcaster, the ABC, which had apparently never asked him to commentate for them. And he had long been contemptuous of many of the arrogant and petty-minded old-line Australian administrators. He genuinely believed the players deserved more money and so, front and centre of Packer's Pirates, alongside the more contentious figures of Packer himself and Tony Greig, there was Peter Pan. Without Benaud to legitimise it, the venture might never have survived its difficult early months. Afterwards, some of his relationships would never be quite the same again, with Bradman most of all. But it made him one of the fathers of modern cricket, and for the quarter-century that followed he would be the most distinctive, most respected and most recognised sight and sound ("Morning, everyone") in both cricketing hemispheres.

He remained ferociously energetic. In England, he continued to write his own column for the otherwise disreputable News of the World, which, like Packer, employed Benaud to give them a veil of holiness (it took columns from a former Archbishop of Canterbury on the same basis). Before a full day's work at provincial Tests in England he would habitually play, not a gentlemanly nine, but a full 18 holes of golf. His golf was in character: every shot carefully considered. Playing with Michael Parkinson in Sydney, Benaud advised his partner that the 18th green was ferociously fast and that he should on no account overshoot the hole. Parky disobeyed and turned a possible three into a seven.

"I know what you're thinking," he said ruefully as they walked off. "You don't," said Benaud. "Because you're still here." Confronted with foolishness, Benaud could always be withering, and he appeared unapproachable. But, among friends, he was a famously genial dinner companion; and anyone who came up to him politely was granted politeness back, and sound advice if requested. He did seem to be good at almost everything. Even his punting was all of a piece. For 30 years, until the week he died, he had a private tipping competition with the shrewd Jack Bannister: one notional bet on English racing every Saturday, loser every six months to buy dinner for four. "Much of the time I was at home, and he would pick horses studying the form-book from Australia," said Bannister. "And he would still stuff me out of sight more often than not."

Richie's original marriage, in 1953, was his biggest failure; his first wife, Marcia, offered a lone dissenting voice amid the funerary tributes, and his relationship with his two sons was fraught. However, Richie's partnership - in life and business - with Daphne, his second wife, was successful and lasting, and their regime of perpetual summer, flitting between their homes in Sydney, London and France, seemed utterly enviable. Some thought driving was not his greatest skill. And when he crashed his beloved Sunbeam Alpine in Sydney in 2013, that and skin cancer - maybe the result of his bare-headed playing days - combined to end his commentary career and hasten his final decline. Perhaps nothing summed him up better than the last of the several pieces he wrote for Wisden: a tribute to his friend and hero Keith Miller in 2005. The editor muttered apologetically about the feebleness of the fee. No, he said, he didn't want a fee. This was a duty, an obligation, the right thing to do.