Australian cricket doesn't have much time for elegance. It looks unserious, brittle, even a little effete. Australians favour aggression - bustling, bristling, business-like. They like to think of themselves as all about effect and output; it's not how but how many. For

Greg Chappell, they made an exception.

The elegance did not, of course, come first. For more than a decade Chappell was the gold standard of Australian batting. He was like bullion in the vaults: the reserve currency. In the speculative side you chose at the pub, you put down his name at No. 4, and then you started with the rest. I dare say Australia's selectors were the same. So Chappell did what was in him, and it happened to be beautiful.

Yet it did matter how he achieved this, by looking a treat. After an early tightening of his technique, there was no stage in Chappell's career when he was not a dazzling strokemaker. Nobody ever enjoined him to "bat ugly"; it would hardly have been possible. He had a bearing, a majesty, even in repose. He might have played three maidens, but if one dropped into the slot you knew it would be on-driven for four; he might take three hours over the first fifty, but the second fifty would take 45 minutes with barely a hint of extra effort.

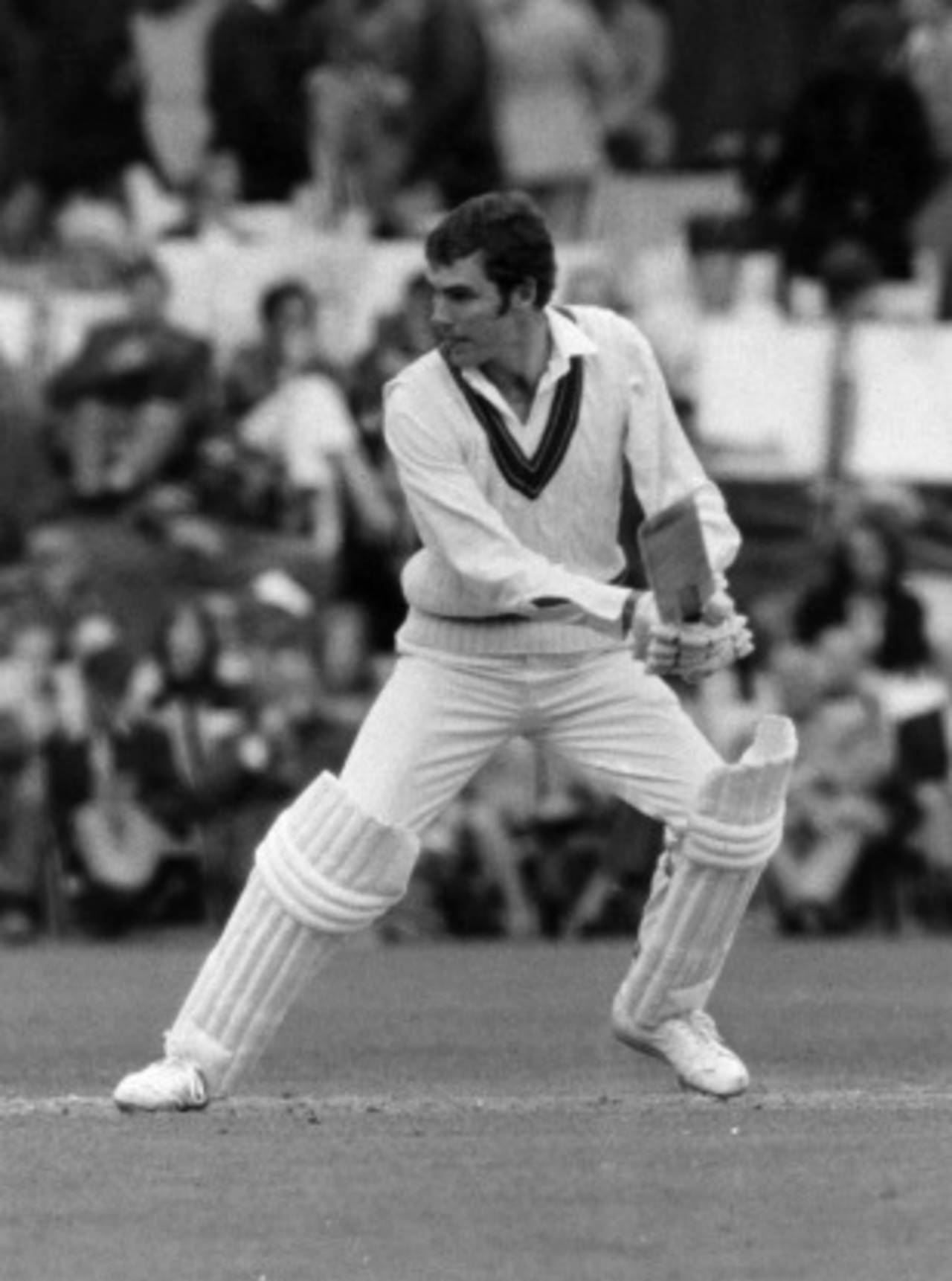

Chappell was a tall, slim, lean man - even a little austere. He played his cover drive from full height. The bat came down straight. The weight surged through the ball. It looked imperious. It was imperious. As a spectator, you felt the wash of disdain - how it must have felt to bowlers. As for the leg side, you sensed he could have nominated any of its 180 degrees and hit it there, particularly behind square, the quadrant into which he directed his signature, wristy, upright flick. He never hurried, never seemed to push too hard, never thrashed or slogged when a stroke would do - he just made up his own rules and followed them, without deviation.

Between balls and times, Chappell looked a little uptight, his pipe-cleaner man's physique emphasised by a shirt buttoned to the neck, sleeves always to the wrist. His stance was stiff-legged, over-topped by a stoop. The bat made a rhythmic tap, before one final, faintly voluptuous loop towards gully. Then, with the ball in flight, everything changed. The bat and body snapped into line. The hands aligned perfectly at slip. Chappell didn't take spectacular catches, fumbles or rebounds - his anticipation was too good to need to. The ball simply vanished and never reappeared.

The effect was strangely humbling. When Chappell reached 200

at the Gabba in December 1981, a spectator bounced off the old Hill there and began hare-ing for the centre, pursued at the plod by security - a year before the misfortune of Terry Alderman, such invaders were an annoyance rather than a threat. It wasn't to slap Chappell on the back or obtain his autograph that this man came either: he took the batsman's gloved hand, went down on one knee and bowed his head, as if genuflecting to royalty. Watching Chappell put John Arlott in mind of William Clarke's description of Joe Guy: "All ease and elegance, fit to play before the Queen in Her Majesty's parlour." It was something to provoke similar spontaneous homage from the Aussie egalitariat.

It was not all patrician airs and drawing-room decorum, of course. Most people know that Chappell scored a century in his

first Test. Not everyone remembers that he did so batting at No. 7, bowling his medium pace as the first-change bowler. He was joining a rather embattled team, recently mauled in South Africa and about to lose the Ashes too. Nor did he immediately impress as a permanent fixture. A couple of months before the Australian team to tour England in 1972 was chosen, his place was uncertain.

Chappell's batting crystallised when abundant natural talent was harnessed by an anchorite's self-control. Early in his career he played his shots with a generous abandon. His biographer Adrian McGregor explains that the admonitions of Chappell's father, and of the respected Adelaide journalist Keith Butler, caused him to undergo some soul-searching. Nine times out of 10, Chappell reasoned, a batsman blew himself up. He must not indulge bowlers so. He sacrificed none of his strokes - Richie Benaud had enjoined him not to. He simply developed a mental self-discipline more severe than any contemporary's. His was the first generation to take the mental side of cricket in earnest, reading Rudi Webster's Winning Ways, visiting the hypnotherapist Arthur Jackson, invoking the "flow" of Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi. They were lucky in already having good techniques - later players thought positive thinking could do the work for them. Chappell, however, was a class apart. He may even have imparted some of his drive to brother Ian, whose average after Greg joined him in the Test team was 12 runs higher than before.

He played his cover drive from full height. The bat came down straight. The weight surged through the ball. It looked imperious. It was imperious. He never hurried, never seemed to push too hard, never thrashed or slogged when a stroke would do - he just made up his own rules and followed them, without deviation

There was something slightly forbidding about this. In contrast to Ian, a natural leader of men, Greg confessed himself only a "workmanlike" captain. Even to team-mates he could look stern, schoolmasterly. Geoff Lawson has described the agonies of entering the Australia team in 1980, of Chappell with hands on hips at slip "as if to say, 'Don't bowl that crap, son,' every time I bowled a half-volley or got hit for a boundary": he deemed Chappell "one of the poorest captains that I had ever played under". His confreres Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh found Chappell a more communicative and empathic captain after he had tasted ruinous failure in the summer of 1981-82. The struggles of others became more explicable in terms of his own.

Chappell's great indiscretion was the underarm delivery. Most cricket conflicts arise from adrenaline, anger, petulance. Here was a rare counter-example, originating in the opposite state of mind, from a coldly rational assessment of problem and of probabilities, involving a solution on Chappell's mind since a one-day match during World Series Cricket had been won off the last ball by a tailender's six. Chappell's decision is generally construed as a momentary lapse, an instance of judgement impaired by tiredness. Yet it might also be seen as one of Chappell's truest actions - evidence of his analytical mind and unsentimental nature. Producers in Channel 9's commentary position used to direct cameramen to vision of Chappell with a terse instruction: "Give us a shot of Killer." Killers are as killers do.

Chappell's self-mastery might have come harder than it appears. He retired twice in his career, once publicly in 1977, once privately in 1982, when his form was at its worst. He also developed considerable business interests, as though he aspired to leaving cricket behind. When they did not really fructify, he remained in the game with a seeming ambivalence. Few men know batting better, but his coaching record is indifferent. He commentates knowledgeably but without much enthusiasm. He quit noisily as an Australian selector in the 1980s, and has returned more than 20 years later, this time in the created role of national talent manager. He is not the only cricketer, of course, to have struggled to find a place in life that suited him as amply as the crease. Nor in art is it rare for beauty to arise from hidden struggle.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer