The fastest bowler I've faced

A tale of Brian Close-like courage and brotherly approval

Samir Chopra

23-Sep-2015

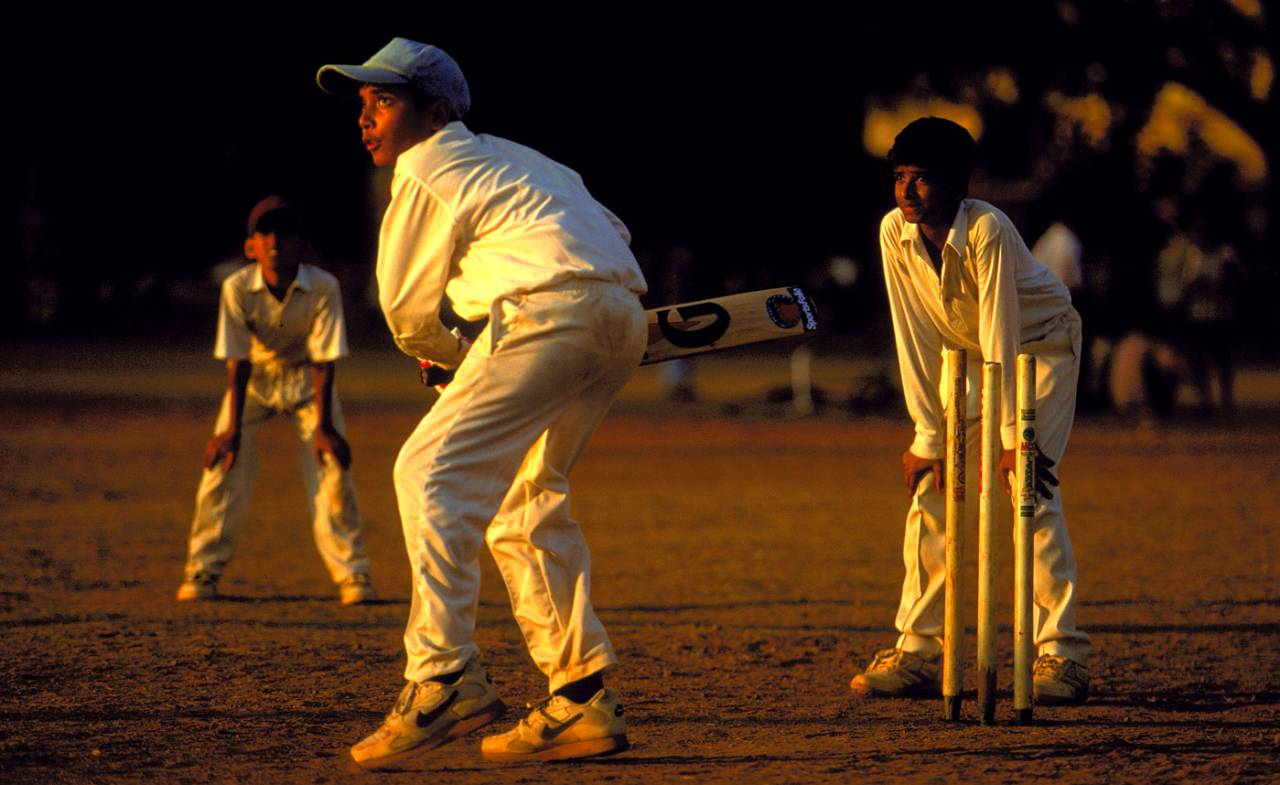

Child's play: sometimes the stakes in neighbourhood games can be as high as those in Test matches • Getty Images

Cricket fans are fond of discussions that centre around the best bowler, the best batsman, the best team - you know the varietals. A central item in this series of disputations is that of the fastest bowler ever.

I've often thought the right sort of entry in this competition would be a fast bowler the fan in question had actually faced. This is not to say that fans should not question matters like the accuracy of a particular measurement of bowler speed, or dispute the margin of error in another one, but rather that the proof of the pudding in this matter really should be in the eating.

So here goes.

The fastest bowler I've ever seen was not a member of any of the famed West Indies quartets, or of any of the many terrible Australian or Pakistani duos that terrorised batsmen and entertained fans the world over. Rather, he was a quick I faced in a lowly park game. I played him for eight overs, perhaps my best batting performance ever. I don't recall scoring too many runs, but that didn't matter, because survival and the even more important business of saving face did.

Like in any "famous" batting performance against fast bowling - think Close against Holding, like I did during my gallant evening stand - I came away with a few body blows and the respect of the opposition. And I did so with only one pad, no gloves, and, needless to say but I'll say it anyway, without a helmet.

Let me set the stage for you, so that this tale of heroism can be best appreciated in its fullest context. In my school days I played, as the other children in my neighborhood did, in our local park. As I noted in another post here, our playing surfaces were badly pock-marked and cratered; batting on them was an adventure. Batting on them while facing anyone who tried to send the ball hurtling towards you was a fear-inducing business. But we played on them anyway. It was all we had.

Our playing group consisted of boys of roughly the same age, and I did not feel out of my depth. This was because by one of those magic acts of self-organisation that make social life so interesting, we found, and stuck with, a peer group of roughly equal playing ability.

I stopped caring about making runs - and truth be told, I was encouraged in this matter by some of my brother's kinder friends, who urged me to keep batting

My brother found his own playing group in another park, one that took a longer walk to get to, and which featured games of ever so slightly higher quality. My brother, older than me by two years, was never too keen to have me mingle with his friends - perhaps fearing I would embarrass him with my undoubted cricketing incompetence. (This apprehension might have been based on his memory of an incident that occurred when we had played soccer together. Then, I had gone down after a brutal tackle by an older boy, and had shown a tear or two on the soccer pitch.) His friends, though, were more encouraging, and would often urge me to join them for a game or two. I never took them up on this invitation, not wanting to defy my brother's implicit warnings to keep my distance.

But one day, while my brother was away, and his friends rolled by to pick him up for a game, they found me instead. On their urging, I joined them. I was a tad apprehensive and a little excited too. Perhaps now I would have a chance to show I belonged; perhaps glowing reports of my play would make it back to my brother. A trial by fire awaited.

All too soon I found myself facing a young man whose reputation as a fast bowler was well known to all and sundry; he already played for my school's junior team, i.e. the 2nd XI. I was out of my league. On realising that he was in the opposition, I felt a sensation that was a curious mix of nausea and fear; my stomach felt like it might give way in both directions all at once. I had seen him bowl in the nets at school practice and there was no doubt he was quick. What's more, he didn't seem particularly friendly, not too inclined to give this kid, his friend's younger brother, an even break. I hoped I would spend his overs at the non-striker's end, well protected by the skilful strike rotation of my batting partners.

Do you freeze or "Close" out when a ball hurtles towards you?•AFP

That was precisely what did not happen. All too soon I found myself facing the Terror. I gazed at his receding back as he strode to the end of his run-up, hoping he would change his mind and turn to crafty offbreaks instead. This hope was soon dashed and I found a red orb rapidly hurtling at my body. It missed everything - bat, stumps, body. The same happened on the second delivery and third. I finally made contact on the fourth ball.

I will happily confess that most of my batting that day was a blur. I could not take a single to demote myself to non-striker, and my batting partners were terrible at taking singles off the last ball at the other end. I dimly sensed that if I gave any indication of fear, word would get back to my brother, and my diminished stock in his eyes would plunge even further.

So I "Closed" it out. I did not back away; I did not flinch; I did not call for help. I defended my stumps and my body as best as I could, and yes, I copped the occasional blow. Thankfully they were all on the fleshiest parts of my body; no bones and no teeth became casualties. I stopped caring about making runs - and truth be told, I was encouraged in this matter by some of my brother's kinder friends, who urged me to keep batting. (I'm a little puzzled why my non-scoring was so tolerated; we were surely playing a limited-overs game and time was always at a premium in these settings. My memory is of no help here. Or perhaps I dreamed it all.)

Finally the quick tired, or rather, others insisted on bowling from his end. He was taken off. Almost immediately I lost my wicket, swinging wildly at his replacement, only to have my stumps uprooted. But my deeds were done. I walked off tired and pleased. And sore.

My batting performance had the intended effect. My friends told my brother I had acquitted myself well; my brother acquired a new respect for me. And that demon bowler? A year or so later, we were co-conspirators in crime, sneaking off to have an illicit cigarette or two together.

I never lost my fear of fast bowling, though. An eminently sensible attitude as far as I'm concerned. And I've still to see a faster spell than the one I faced that day, in the fading light of a north Indian winter, on an occasion when the stakes, personal ones, were great.

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. @EyeonthePitch